My Share of the Task (26 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

My command-and-control headquarters, a few feet away through a plywood door, followed the same logic. Most of our quarter of the hangar comprised what we called the situational awareness room (SAR): I worked primarily at the head of a rectangular horseshoe table that faced a wall of screens. My intelligence director, operations director, and command sergeant major flanked me. Liaisons from more than half a dozen agencies eventually sat at the same

U

-shaped table, though in the summer of 2004 only the CIA seat was filled.

The SAR reflected how my command style and command team were evolving. As I stressed transparency and inclusion, I shared everything with the team sitting around the horseshoe and beyond. E-mails that came in were sent back out with more people added to the “cc” line. We listened to phone calls on speakerphone. (Rare exceptions to this policy of transparency were sensitive personnel issues and cases when sharing would betray someone's trust.) As a result, I increasingly found T.T. and other senior officers could frequently anticipate my position on an issue and make the decision themselves.

While effective, this immersive command approach was also a bit like playing the run-and-gun style of basketball I'd preferred in my youth. It required almost nonstop focus. My command staff and I often discussed urgent decisions, all while keeping an eye on the screens depicting ongoing operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. It could also lead my full attention to snap to near-term issuesâwhat we called “pop-up targets” after the silhouette figures on army marksmanship ranges. Aware of this pitfall, I tried to create venues for strategic thinkingâfrequently gathering members of my command group, subordinate task forces, and an intelligence analyst with in-depth knowledge so we could stew in a topic.

I lived in a plywood hooch about twenty meters from the entrance to the bunker. I shared it with my command sergeant major, Jody Nacy, and operations sergeant major John Van Cleaveâboth extraordinary soldiers and close friends. I slept on a cot-size, metal-framed bed that spanned the width of the room. On nails and screws I put into the plywood walls I hung backpacks and equipment and tacked up pictures of Annie. The room was spare but convenient. I believed it reinforced the message I preached about focused, unadorned commitment.

Until we won, this was home.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

A

s we were establishing our base in Iraq, so too were Al Qaeda's top leaders. Sometime in the late summer of 2004, Abdul Hadi al-Iraqi, a Mosul-born Al Qaeda lieutenant working in Pakistan, reportedly made his fourth and final trip to Iraq as an emissary

between bin Laden and Zarqawi. He arrived to mediate an agreement at what was a tense time between the two camps. Al Qaeda was increasingly hampered, while news-making Zarqawi was still not fighting under its formal banner.

Since Zarqawi had sent his letter to bin Laden and Zawahiri the previous January, tentatively requesting their formal support, they likely were hung up on whether to endorse the most controversial pillar of Zarqawi's Iraq strategyâthe

unrestrained targeting of Shia Muslims. The rogue Jordanian likely forced Al Qaeda's hand, as the strategy was already going full bore. In their discussions, Al-Iraqi probably told Zarqawi he needed to curtail his “messaging”âthe carnage and beheadings his group broadcast abroadâto avoid tarnishing the Al Qaeda brand. They likely haggled over whether Zarqawi needed permission to launch attacks outside Iraq. A red line was surely that Zarqawi could not publicly

challenge Al Qaeda's leadership. When al-Iraqi left Iraq and returned to Pakistan, he likely did so with an agreement from Zarqawi in hand, for soon Al Qaeda's network would officially have a new franchise.

Around this time, Bennet Sacolick, commanding Green, came into my office to brief the command. Tall, with long limbs, a thin face, and closely cut graying hair, Bennet looked more like a high-school basketball coach than a veteran commando. And he was different. Thoughtful, talented, and pleasingly iconoclastic, he could also be headstrong and slow to carry out changes with which he didn't fully agree. I could live with that. This was a force of strong-willed professionals, and I had learned it worked best to harness, not constrain, their energy and ideas. He had the tricky responsibility of commanding Green as it moved from what it wasâan insular, powerful fiefdomâto what it would beâone of the most important nodes in an integrated network.

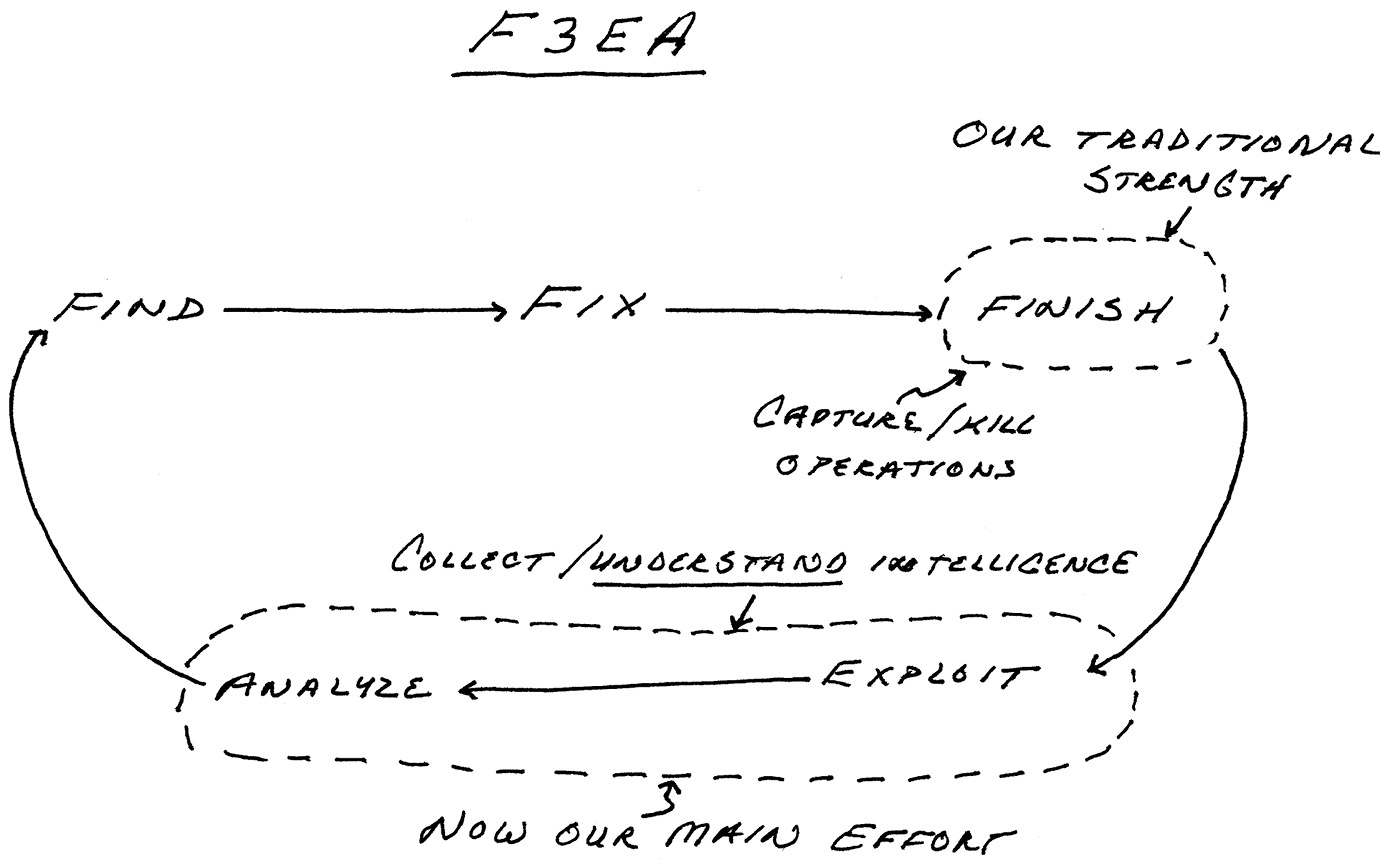

Bennet put a single PowerPoint slide on the monitor, with five words in a line. Its simplicity belied how profoundly it would drive our mission to be a network:

FINDâFIXâFINISHâEXPLOITâANALYZE

The words represented our targeting cycle: A target was first identified and located (Find), then kept under continuous surveillance to ensure it hadn't moved (Fix), while a raid force moved to capture or kill the targets (Finish). Material of intelligence value was deliberately secured and mined, while detainees were interrogated to find follow-on targets (Exploit); the information this exploitation yielded was then studied to better know our enemy and identify opportunities to further attack its network (Analyze).

The military had used targeting cycles like this for a generation. But the task in Iraqâfinding and stopping insurgents, not Soviet tank columnsâdemanded radically faster and often very precise execution. Innovative Green operators and commanders, including Scott Miller and Steve, the squadron commander from Big Ben, had outlined F3EA, as we called it, the previous January as they turned their attention from rounding up former Baathists to attacking Zarqawi's emergent organization.

Bennet's brief captured an important and sometimes misunderstood layer of complexityâwhat he described as the “blink” problem. A blink was anything that slowed or degraded the process, which often involved a half dozen or more units or agencies working in as many locations. Between each step, information crossed organizational lines, cultural barriers, physical distance, and often time zones.

“By the time we're ready to go after another target,” he said, impassioned but focused, “it's often days later, the situation has changed, and we're essentially starting from square one.” The process felt slow at the time. In retrospect, it was glacial.

Only part of this was due to our not-yet-robust technology infrastructure. Most of it owed to a lack of trust among the participants. In the world of intelligence, information was power, leading people at each stage to ask themselves a set of questions:

Should we pass this intelligence, and if so, how much? If we share it, will we lose control over it? Will we get in trouble for sharing this information? Will those we pass it to use it in the way we agreed they would?

These doubts cost us speed and often diluted the intelligence, making it less likely to lead to targets.

An initial and soon fixed example involved the National Security Agency, one of our closest partners, which specialized in signals intelligence. By practice, the NSA provided us with condensed summaries and analyses of the signals it intercepted. TF 714 wanted to see raw intercepts right away, before receiving the NSA's summaries a few days after the fact. Initially, the agency refused. The NSA was understandably concerned that we lacked the in-house expertise to avoid misinterpreting and misusing unfiltered information. But it also saw the analysis of signals intelligence as its proprietary domain and was reluctant to relinquish that unique role. Discussing this in terms of “blinks” helped us to identify and parse these choke points and to empathize with the viewpoints and incentives of our partners, like the NSA.

We knew eliminating “blinks” would have a dramatic payoff but would require changes equally significant: They had to be physical, organizational, procedural, andâmost importantâcultural.

Indeed, the greatest chance for improvement lay in how people felt about their involvement. Everyone needed to trust counterparts (especially those whom they'd never see in person) and believe in the network premise itself. To spark this, we in TF 714 leaned hard on our operators to use video teleconferencing to improve the frequency and quality of their interactions. We instructed our people to share more than they were comfortable with and to do so with anyone who wanted to be part of our network. We allowed other agencies to follow our operations (previously unheard of), and we widely distributed, without preconditions, intelligence we captured or analysis we'd conducted. The actual information shared was important, but more valuable was the trust built up through

voluntarily sharing it with others.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

M

uch of my and my command team's time was spent solidifying the partnerships with the half dozen agencies involved in a single cycle of F3EA. I knew the creative solutions to eliminate blinks would originate from those closest to the fightâand closest to the hiccups.

So while most members of the force were self-starters by nature, I needed them to operate without waiting for detailed instructions or approvals. TF 714's leaders and I tried to set a climate in which we prized entrepreneurship and free thinking, leaned hard on complacency, and did not punish ideas that failed. “As long as it is not immoral or illegal,” went my frequent refrain, “we'll do it. Don't wait for me. Do it.” On nearly every visit across the force, I asked, “What more do you need?” then fought tooth and claw to get team members any resources they legitimately needed. I wanted to leave them with the sense that nothing was impossible, that there were few valid excuses for not accomplishing the mission, and that even those processes not broken needed fixing. I was rarely disappointed and frequently awed by their solutions.

Although some decisions had to be approved by TF 714's leadership, we pushed authority down until it made us uneasy. More than once I encountered equipment we'd purchased or tactics we'd adopted that made me worry I was negligent in oversight. But I thought of the alternativeâcorseted centralizationâand that squelched my inclination to grab control. At the end of 2005, I listened to the audiobook of Adam Nicolson's

Seize the Fire

; it did a lot to clarify why Nelson came to mind as TF 714 redefined itself. “

He would create the market,” Nicolson wrote about Nelson, “but once it was created he would depend on their enterprise. His captains were to see themselves as entrepreneurs of battle.”

Rarely did any one thing transform our capacity, and few ideas could be traced back to one person. Rather, after weeks and months of incremental changes, what we had once considered swift was slow, rudimentary, or inefficient by comparison. In order to better triage and translate captured documents, for example, we first hired more Arabic linguists. But we only saw exponential improvement after the Defense Intelligence Agency's (DIA) National Media Exploitation Center contributed a powerhouse of capability we could never have created ourselves. To pump terabytes of images and video to them, we augmented the thicket of antennae on our hangar roof with a grove of huge satellite dishes. We learned to feed their linguists intelligence about raided targets, so they had valuable context to help them parse the material. The operators, seeing greater value arise from captured documents, became more focused and effective at retrieving themâno more trash bags labeled with a sticky note.

As one part of our process improved, a new choke point would appear, and the innovation would continue. TF 714 instituted “exploitation VTCs” by installing cameras in the garagelike rooms where our exploitation teams worked in Balad, so that by video link specialists in D.C. or in other parts of Iraq could weigh in on the material only minutes after it was captured. We developed a “portal,” essentially a Bloomberg-like terminal that stored a library of intelligence on Al Qaeda. We also uploaded instructional videosâ“How to Be a Liaison Officer” was one of the bestâand posted important memoranda everyone needed to read. The number of people accessing the information soon bloomed to thousands.

The catalyst to turn so many of these concepts into reality was then-Colonel Mike Flynn, TF 714's J2 or intelligence chief. After I sought his appointment, he joined our force in July 2004 and for the next three years would direct every aspect of the intelligence that is the lifeblood of counterterrorist and counterinsurgency operations. Mike was pure energy, and it infused his aquiline face and posture. With neatly parted dark hair, a sharp jaw and nose, and a lean athletic build, he looked spring-loaded. In conversation, his eyes locked your gaze and his passionate, raspy Rhode Island clip quickened when he hovered over a notepad. He had an uncanny ability to take a two-hour discussion or a thicket of diagrams on a whiteboard and then marshal his people, resources, and energy to make it happen. The green notebooks he keptâfilled with elaborate notes and printouts of slides and imagesâwere bulging compendiums of TF 714's conceptual growth.

Mike's impact was distinct. He arrived as it became clearer than ever that our fight against Zarqawi was, at its heart, a battle for intelligence. And yet when he and I surveyed TF 714's outstations and liaisons during the first few weeks of his tenure, we found ourselves largely focused on the fix and the finishâthe tactical strikesâeven though the exploit-analyze portion of the cycle would determine our success or failure. Some time would pass before the whole forceâwhich saw itself as the best tactical and operational wing of the militaryâbought into this. Our physical expansion that summer sped the process: We weren't building more shooting ranges at Balad. We were accruing facilities and resources devoted to collecting intelligence and to understanding the enemy. By the time he left, we had

a brigade-size force of intelligence people throughout Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. This did not happen easily. We often had to scrounge for analysts and interrogators, and Mike built much of this force a pair or a handful at a time.