My Share of the Task (21 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

Witnesses later reported to the French consul in Baghdad that “

12,000 Wahhabis suddenly attacked Imam Husain,” killing men, women, and children. “It is said,” he reported, “that whenever they saw a pregnant woman, they disemboweled her and left the fetus on the mother's bleeding corpse.” The Wahhabi attack was religiously motivated but caused political disruptions. It weakened the central authority in Baghdad, showing it unable or unwilling to protect Shiites and their holy sites. This provoked the Persians, who would need to come guard their fellow Shiites and their sacred mosques.

In the two centuries between the rise of al-Wahhab and the emergence of Zarqawi, a number of strains competed and overlapped within the radical wing of Sunni Islam. Zarqawi's Salafist jihadism owed much to the Wahhabi creed, though in its violent political manifestation that Zarqawi pushed, it sought to outdo the Wahhabis where they were

too passive or too compromising. While anti-Shiism was ingrained in these ideologies, even the most violent Salafist groups that emerged in the late twentieth century had

largely avoided the sectarian targeting on display in Karbala in the spring of 1802. Strategically, Zarqawi resuscitated that hatred, and in the spring of 2004 he prepared an attack on that same Iraqi city with largely the same religious motivations, aiming to achieve strikingly similar political aftereffects.

The strike augured a campaign strategy that had become clearer to us at the end of January. In spite of the attacks Zarqawi orchestrated in the fall of 2003 against the U.N. and the ICRC, we were not certain he was in Iraq until the end of the year. But with Saddam now captured and the remnant Baathists increasingly rolled up, Zarqawi became our primary focus. As he did, our understanding of him took an ominous leap forward.

During the third week of January, Kurdish Peshmerga forces arrested a Pakistani Al Qaeda operative named Hassan Ghul near Iraq's northeastern border. Acting as a courier, Ghul was carrying two CDs and a thumb drive, which yielded a letter written from Zarqawi

to bin Laden and Zawahiri. A dispatch from Iraq, the letter described the scene for the senior Al Qaeda leaders holed up in Pakistan, and laid out the strategy Zarqawi would pursue with brutish consistency for the next two and a half years. The Americans were a threat, he acknowledged. But like bin Laden before him, Zarqawi dismissed us as a paper tiger. “

They are an easy quarry, praise be to God.” Rather, the Shia were the “insurmountable obstacle, the lurking snake, the crafty and malicious scorpion, the spying enemy, and the penetrating venom.”

The Iraqi Sunnis had yet to realize this threatâor to coalesce behind Zarqawi's ranks. So he cast his foreign jihadists as the true keepers of the faith, the hard edge of the insurgency, and the only defense against the Shia. To jolt the Sunnis from their torpor, in which, he contended, the Shia would slaughter them, Zarqawi had a simple strategy. He planned regular and merciless attacks against Shiite civilians, which would provoke Shia reprisals until the back-and-forth escalated to full sectarian war, stoking the rage and sympathy of Sunnis worldwide and bringing the “Islamic nation” to the fight as volunteers and supporters. The new Iraqi government, which the Shia were clearly going to dominate, was the main obstacle to making Baghdad the seat of the reestablished caliphate. Only in the high pitch of an ethnic war would the Sunnis win. In that hell, Al Qaeda would reign.

The Coalition released the letter to the public. Three weeks later, Zarqawi made good on his promises. On Tuesday, March 2, Shia believers from around Iraq and from abroad entered Karbala, the site of the Wahhabi massacre 202 years earlier. For the first time in

almost thirty years, these Shia were free to celebrate Ashura in that holy city. For decades, a political desire to suppress Shia identity had driven Saddam to ban the festival.

That Tuesday morning, Zarqawi's operatives, outfitted with suicide bombs assembled in Fallujah garages, were positioned inside Karbala. Others waited to fire mortars into the crowd, as a prominent Kuwaiti cleric damned the Ashura rituals that would take place that day as “the world's biggest

display of heathens and idolatry.” At 10:00

A.M.

, with the streets lined, multiple suicide bombs exploded where people were most densely packed in the streets, near choke points,

outside a hotel and a shrine. Desperate pilgrims beseeched the panicked crowds not to step in the pools of blood or on the bits of flesh and limbs scattered on the pavement, to avoid profaning them. At roughly the same time, multiple bombs popped in a Shia neighborhood in Baghdad. All told, the day ended with at least

169 dead and hundreds wounded.

Zarqawi's campaign against the Shia was more than political. It was fueled by a visceral hatred and repugnance and a dogmatic theological commitment. But as the 1802 massacre had done for a spell, Zarqawi's Ashura bombings, the loudest of an increasing drumbeat of anti-Shia attacks, succeeded in nudging the political realignment his strategy required. Zarqawi wanted Iraq to be contested by extremists, not forged by moderates. Shortly after the twin attacks in Baghdad and Karbala, militias patrolled these cities, portraying themselves as the

protectors of their fellow Shia. If Shia lost faith in the ability of the new Iraq project to secure them, they might turn to the volatile militias, the Iranian-backed Badr Brigades, and the growing if more ragtag ranks of Muqtada al-Sadr. These more radical, demagogic groups were liable to conduct anti-Sunni reprisals.

And yet civil war did not erupt that spring. Zarqawi's persistent and fatal campaign of anti-Shia attacks did not set off the sectarian schism he sought as early as we thought it would. At that time, at least, sectarian war was not in the long-term interest of the Shia, who, as the majority, would be empowered under a democracy. Even while patrols of Shia militias took to the streets, Shia clerics worked to discount Zarqawi's narrative and dampen sectarian feeling, blaming the Americans instead of the Sunnis. This reflected considerable restraint and, less charitably, a fractured and disorganized Shia political community.

Armchair analysts too often caricatured Iraq as a place of sectarian tinder that was easily lit after we removed Saddam. It was easy to forget, having watched the country fall into civil war, that Iraq in the fall of 2003 and spring of 2004 was not riven along sectarian lines. Iraqis rarely thought of themselves primarily in religious or ethnic terms. Although the Sunni-Shia split had been exploited and frozen under Saddam, there did exist a national Iraqi identityâin part attained through common aspirations toward unity, in part forged in the trenches and minefields along the border war with Iran in the 1980s. While a contest over resources and political power was inevitable, there remained genuine interestâamong Shiites and Sunnisâto work with the Americans following Saddam's fall. The ease with which we forget this factâand the stubborn refusal of Iraqi leadership to overcome the sectarian paranoia once it became entrenchedâis a legacy of Zarqawi.

Zarqawi aimed to get Iraqis to see one another as he saw them. And to him they were not countrymen or colleagues or neighbors or in-laws or classmates. They were either fellow believers or an enemy to be feared and, in that fear, extinguished. Zarqawi's rabid anti-Shiism increasingly drove his organization to be less focused on driving the Americans out of Iraq and more bent on attacking Iraqis. In the years ahead, Zarqawiâobstinate and powerful enough to fend off criticsâalmost succeeded.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

T

hat spring, the logic of Zarqawi's violence was hazier than it would become later. But the sheer ferocity of these attacks, and the terroristic tendency they lent to the insurgency, convinced me this fight would be long and difficult. From history, I knew of the moral and political traps awaiting forces conducting counterinsurgency or counterterrorism operations, and I wanted us to confront them directly before we found ourselves acting in ways counter to our values or our cause. TF 714 would need to acquire roles and expertise that would demand clear mental, moral, and operational focus. For this reason, I called my commanders together for a conference at Bagram the first week of April 2004.

Periodic commanders' conferences were especially valuable for TF 714. Given our geographic dispersion and the insularity and elitism ingrained in some of our units, they helped us build a sense of teamwork across the force and aligned our strategy. The Bagram conference convened key TF 714 staff; the flag officers heading the country task forces; and commanders, deputy commanders, and senior enlisted advisers of the component units. Everyone flew into our base on the Bagram airfield. There we still operated out of big canvas tents and rudimentary plywood huts filled with metal folding chairs and folding tables.

As early as our October trip, Scott Miller, the Green deputy at the time, had said we would be deluding ourselves to think we weren't facing a full, and growing, insurgency in Iraq. He had been reading about the French experience in the insurgencies of the midcentury. We had both read

Modern Warfare

, a compact 1961 treatise by the French military theorist Roger Trinquier, but I read it again that spring after Scott passed me a photocopy of the book. While we disagreed with many of the hard-edged solutions Trinquier endorsed, his analysis of the challenge was instructive.

At the conference I decided to show

The

Battle of Algiers

. The film is a fictional but historically accurate portrayal of the French 10th Parachute Division, which deployed in 1957 to secure the city after the National Liberation Front (FLN) insurgency overwhelmed the ability of the Algiers police to suppress it. Additionally, I had the commanders read

Modern Warfare

, but I did not attach any message or opinion when I sent it to them. I wanted them to come with fresh opinions. We also brought Professor Douglas Porch, one of the foremost scholars of French military counterinsurgency campaigns, to Bagram from California.

On the morning of the second day, we watched the film and then had a lively two-hour discussion. Intentionally, I allowed the conversation to flow. As is so often the case, the senior enlisted advisers, in particular, were sharp students of these issues. I felt it was critical that these leaders drew and articulated their own conclusions. But they also needed to understand my personal view, so there could be no ambiguity about what I expected. In order to show the thinking that led to my conclusions, I reminded the group of two powerful scenes from the film. The first showed the fundamental ignorance of the French about the deeply ingrained nature of the FLN insurgency in Algerian daily life. Pointing to one of the walls, I told the group assembled, “We fundamentally do not understand what is going on outside the wire.”

The second scene addressed torture head on. I believed thatâeven with the heated post-9/11 outrage felt by Americansâsuch a tactic would be self-defeating, and the film opened a window for me to address concerns I had about our nation's detainee operations since I had taken command. I had been deeply unimpressed with the interrogation facilities at Bagram when I first deployed to Afghanistan in 2002. Our nation's lack of institutional wisdom gnawed at me. In preparing for the conference, I distilled two thoughts. First, how we conducted ourselves was critical, and the force needed to uniformly believe that. Doing less would dishonor the service of those I led. Second, I was convinced that detainees presented an operational risk: If we got it wrong, TF 714 would be taken out of the fight and might even be disbanded. Three weeks after our conference, we saw the pictures CBS broadcast of Americans abusing prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison. The rest of the world, of course, saw them as well.

As we were meeting, events in Iraq were altering the course of the war and TF 714's relationship to it. On the day the conference began, then-Colonel Bennet Sacolick, the commander of Green, called from Baghdad. He needed to stay in Iraq, he explained, because four American contractors had been ambushed and killed in Fallujah, which was then beginning to tremor with widespread violence.

When I had made the decision the previous fall to hold the April commanders' conference at Bagram, our main focus had been in Afghanistan and neighboring Pakistan, where the primary Al Qaeda threat was amassed. The events in the weeks that followed the contractors' killing would change all that. The grisly images from the Fallujah attackâand the convulsive violence they auguredâsoon made the purse bombs and chicly dressed Algerian terrorists from

The Battle of Algiers

seem quaint.

| CHAPTER 9 |

Big Ben

AprilâJune 2004

I

n early April 2004, the meltdown in Fallujah cut short my stay in Afghanistan. Until that time, my command group and I had largely flown around theater on scheduled conventional military flights. Now we summoned one of our MC-130 special operations aircraft in the middle of the night. Listening to the throaty rumble of the planes' engines across the darkened tarmac, I was anxious to get to Iraq. I sensed that the tenor of the war had changed and that a critical point in the fight against Al Qaeda was waiting for us there.

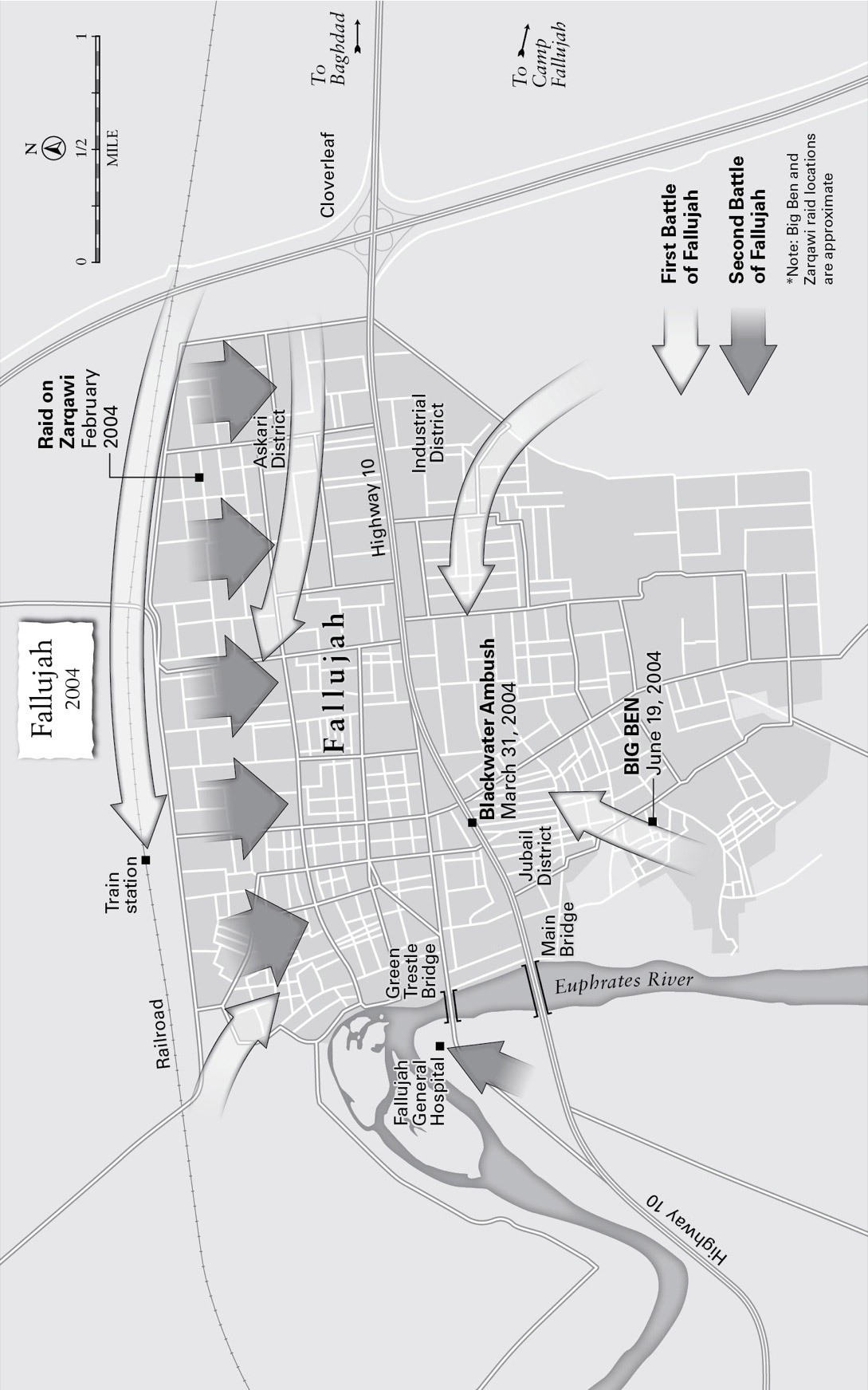

A week earlier, a very public horror show in Iraq had prevented Bennet Sacolick from attending our commanders' conference in Afghanistan. The previous Wednesday, three trucks with empty flatbeds had driven down Highway 10 into Fallujah, en route to the American base west of the city to

pick up kitchen equipment. This was more dangerous than it sounds. Four American contractors, working for the private security firm Blackwater, split between two unarmored Mitsubishi Pajeros, escorted the trucks. At the entrance to the city, a group of Iraqi national guardsmen joined the convoy. The vehicles were

stopped at a checkpoint on the east side of the city and apprised of the Marines' assessment of the dangerous situation. But they continued on. Already, insurgents had planned an ambush. That morning, shop owners along the route had reportedly shuttered their storefronts and terrified residents hid indoors, while the insurgents had prepared the emptied street for the assault.

The American convoy drove along the main road through Fallujah. It continued past the corner where, weeks earlier, our TF 714 vehicles had taken a right into the residential neighborhood where we had searched houses, looking for Zarqawi, and found glaring faces. Once into the denser commercial center of town, the contractors entered the kill zone. The cars in front of the second American SUV halted, boxing it in. Insurgents rushed toward the car from the sidewalks, firing AK-47s, perforating the Pajero's red doors and windows. With the pop of gunfire behind them, the lead SUV tried to maneuver, accelerating, then leaping the raised median. But insurgents were quickly only feet away from the vehicle's windows, raking the car with bullets. They fired until the Pajero slammed into another car and juddered to a stop,

its driver slumped over. The four Americans died in their seats.

With camcorders rolling, a crowd rushed to the cars and set them ablaze. When the flames subsided they dragged the bodies onto the pavement. They beat the corpses with sticks until they fell apart and trailed the bodies, or parts of them, behind cars. A maroon sedan honked playfully as the crowdâwhich reportedly included Iraqi police, children, and womenâcircled around the back bumper and shouted, “Fallujah is the

cemetery of the Americans!” Paper fliers saying the same had been printed and distributed to the crowd to hold up

in front of news cameramen. The crowd and cars moved to the southwest edge of town, where they tied the charred remains of two Americans to the beams of the green trestle Old Bridge. Men and young boys climbed the supports in order to reach out with sticks and shoes to hit the blackened, deformed corpses swaying over a crowd assembled and chanting below. One Baghdadi told the

Los Angeles Times

“with disbelief” that in Fallujah he saw “adolescent boys . . . carrying pieces of charred human flesh on sticks â

as if they were lollipops.'”

This was the most grievous display of overt resistance to American control since the war began. It hit close to home: One of the contractors was a former Navy SEAL, and the other three were former Rangers. Wes Batalona, who had been our operations sergeant at the 3rd Ranger Battalion in 1988 and 1989, was in the driver

seat of the lead vehicle. The images recalled the decade-old videos showing the bodies of men from our command being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu.

Even before this eventâand the two subsequent loud, dusty, bitter urban battles fought in the cityâgave the name “Fallujah” a sinister if vague ring to Americans, the place had been tinder under the American occupation. I had visited a few times that spring and knew the

city of 285,000 was a religious place. Once an ancient nexus of trade routes, it was now a tough trucker town and a smuggling hub. But it was also deeply conservative and proud of its moniker “city of mosques,”

boasting 133 of them. Industrial compounds just north of the city had

produced chemical weapons for Saddam, drawing the suspicion of the U.N. inspectors.

By the time I arrived in Baghdad on Monday, April 5, Marine battalions had breached Fallujah's outer rim, entering all four quadrants of the city in the opening stage of what became known as the First Battle of Fallujah. They began their assault at 1:00

A.M

., having cordoned the city the night before. Others have well documented the grinding, costly battles for Fallujah, waged largely by the Marines. But unknown to most, the events there shaped TF 714 and changed our story, as we accepted an expanded role in the fight. Even then I didn't know the city would take center stageâand that events there would alter the course of the war. Nor did I fully understand the conditions in the city that would vault Zarqawi and his network, in turn spurring our force's evolution to contain the jihadists' violent expansion.

The city that would host this first clash between TF 714 and Al Qaeda in Iraq had

a long, combustible history. To limit resistance to his control in Fallujah, Saddam established a

system of patronage with the Sunni tribesmen of the town, frequently recruiting his government officials from the city, which was

home to many military officers. Many of these Baathists returned to Fallujah after their army was disbanded in May 2003, seeding the city with disgruntled, trained military men. The city's complex social mixture, relatively inert under Saddam, grew more combustible due to American actions.

The 82nd Airborne was responsible for the city following the fall of Saddam in April 2003, but the population quickly turned against them. In truth, the people may never have been theirs to win. Rumorsâlike that suggesting that the paratroopers'

night-vision goggles allowed them to see through the garments of Fallujah's womenâincreased distrust and hostility. On April 28, 2003, soon after the U.S. invasion, a crowd of about 150 Fallujans marched on a school the 82nd had occupied, demanding the paratroopers vacate. Reports differ as to what provoked the violent clash that followed. According to the 82nd, they returned fire after being shot at by youths in the crowd. Fallujans claimed the crowd had no guns and called it an atrocity. In the end, seventeen Iraqis were dead and

another seventy-five injured. They remembered that the Americans offered no apology, no monetary

compensation even as a gesture. Fallujans would refer to the shooting as “

the massacre” for years afterward, and although the Marines who took over from the 82nd sought to dispense money for the damages, many of the

proud Fallujans rejected it.

A year later, during the final week of March 2004, the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force was set to take over all of Anbar. In the weeks leading up to the transfer, Fallujah had become increasingly hostile. In addition to the unsuccessful night raid described in the previous chapter, I had gone to the city several other times to meet with 82nd Airborne leadership. Stretched thin, the 82nd ran only limited patrols through the city. On February 12, General Abizaid had gone with the division commander to visit a new Iraqi army unit organized in Fallujah. As John and the Iraqi boss of the unit chatted in Arabic,

rocket-propelled grenades hit their compound, fired by insurgents from nearby rooftops. John left calm and unscathed, but two days later the same compound was hit again. In a sophisticated assault, fifty insurgents spread across the city and attacked that Iraqi army compound to prevent its soldiers from coming to the rescue of the much less fortified mayor's office and police station, which another group of insurgents was striking. They

freed eighty-seven prisoners and killed at least

twenty Iraqi policemen. As insurgents gained a foothold in Fallujah, they used it as a base of operations. From there, earlier that March, Sunni insurgents had dispatched the suicide bombers to Karbala and Baghdad for the attacks on the Ashura procession. Later that spring, a jihadist tape surfaced. “If John Abizaid escaped our swords this time,” said the speaker, believed to be Zarqawi, “we will be

lying in wait for him.”

Before the attack on the contractors, I spoke with thenâMajor General James Mattis, commander of the 1st Marine Division, about his plans for handling Fallujah and the other hot spot down the road, Ramadi. Our conversation was the first time we had spoken. For the bitter fight he was heading into in Anbar, he would need both of his personalitiesâMad Dog Mattis, commander of the lethal Devil Dogs, and the cerebral student of people and ideas who had an anthropologist's curiosity and appreciation of nuance. Backed by the specter of the former, he would lead with the latter.

“We're planning to do this differently,” he said. “I want us to take off the Kevlar helmets.” He talked about engaging the population. “We're going to go in on foot and fan out in small patrols across the city.”

His intent was to establish a more continuous, more visible presence among the residents, and in the short time before they deployed, Jim tried to give one platoon in each battalion additional language and cultural training. He even arranged for help from the

Los Angeles Police Department. The Marines grew mustaches as a small but resonant gesture of cultural assimilation and amity toward the Iraqis. At the time, I knew there was a plan for his Marines to wear dark green forest camouflage print and shiny black boots for the first part of their rotation. The uniform choice was meant to differentiate them in the eyes of the Fallujans from the 82nd, who had worn beige and brown desert fatigues. Neither of us thought simply being in soft caps would win Fallujah. But Mattis, early on, understood that perceptions were at least as important as any tactical gains.

As they assumed control of the city that March, the Marines began to carry out Mattis's approach, starting with foot patrols. Against determined insurgents, this was dangerous. On Thursday, March 25, in the same Askari neighborhood with row houses that I had walked

through a few weeks earlier, insurgents killed one Marine and wounded

two more with homemade bombs. The Marines returned to the neighborhood the next day, eventually taking control of

the cloverleaf to its east. Our TF 16 forces worked closely with the Marines, gathering intelligence and running pinpoint raids while the Marines provided a steady presence. On the night of March 24, one of our Green convoys was ambushed outside of town. In the massive ensuing firefight, with operators using vehicles as cover, one of

the detainees got away. A week later, the American contractors drove into this rising simmer.

It was the beginning of a difficult chapter in the Iraq war. For the first few days after the March 31 ambush on the Blackwater convoy, the attack did not appear to derail the Marines' plan for clearing the city of insurgents. Mattis's troops focused on retrieving the remains of the contractors, which they did with the help of the local

police chief in Fallujah. The Coalition collected intelligence on the crowd and ringleaders and would have enlisted our help in plucking them from the city. From Afghanistan, I waited and watched. But Washington wanted to answer the murder and mutilation of the security contractors, and rapidly secure the city. The Marines bitterly disagreed, wanting to manage Fallujah on their terms, not as a rushed reaction to the insurgents' baiting. They were overruled. General Mattis was ordered to attack the city

within seventy-two hours. Helmets would go on and stay on.

The commander of our Fallujah-based team decided to seed Marine platoons with Green operators, in ones and twos. These dispersed teams were not only valuable for their experience but also better connected to one another and to the command center in Fallujah than many of the Marine platoons with which they found themselves. Our technology, combined with the agility and experience of the operators, allowed us to gain a quick, robust picture of what they found inside Fallujah. I became addicted to this ground-level reporting for the rest of the war.

Shuttling between my headquarters in Baghdad and outposts in Fallujah and nearby Ramadi, I did not find the teams' reports encouraging. The Marines faced significant but yet unspecified resistance shortly after entering the city limits. We knew Fallujah hosted nationalistic Sunni insurgents seeking to expel the Americans and win political and economic privileges in the Shia-dominated new Iraq. More modestly, these Iraqis were fighting to preserve their pride. We also knew that Fallujah was a nexus for tribal criminal networks, making for a glut of arms and money. Most troubling were the Salafist jihadists in the mix. The same trading routes that now made Fallujah a smuggling nexus for refrigerators and cars had imprinted the city with the ideology of the fundamentalists who had sacked Karbala in 1802. Fallujah sat along the corridors that connected the wellspring of Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia with the region's other great citiesâ

Mosul, Aleppo, and Amman. Much of Anbar was insular, but Fallujah's sympathetic mosques and history as a place of transit lured a trickle of foreign jihadist volunteers.