My Share of the Task (17 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

After I answered questions, our meeting ended, and I left the conference room and walked down the long, sunlit hallway to the front of the compound. Spaced along one wall were glass-encased displays a couple feet deep and a few feet wide. Each documented one of the unit's significant operations or missions. Dusty guns, equipment, maps, and photos rested behind blurbs about each accomplishment.

In the years ahead, they would have reason to install more displays.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

B

efore arriving at my new command, I'd communicated to the TF 714 staff that as soon as practical I wanted to take a trip to the region where our forces were operating, a theater that included Iraq and Afghanistan and stretched from the Mediterranean to the end of the porous Durand Line. We programmed about ten days for the trip. Several key leaders accompanied me, including my J2, or intelligence officer, Colonel Brian Keller, a former Ranger whom I'd known and trusted for years. Brian was soon to move on from TF 714 to another command in a few months, and would eventually be promoted to brigadier general, so I wanted to leverage his experience and expertise before I lost him.

The other half of the key J2-J3 dynamic was my operations officer, Colonel T.T. He and I had worked together as Ranger captains in the 3rd Ranger Battalion in 1987â89. I had recognized his talent, but we were both intensely focused young officers, maybe a bit too much alike, and our relationship was initially strained. As we both advanced in rank and experience, so too did my appreciation for T.T.'s qualitiesâhis amazing vision, unwavering loyalty, and personal courageâand we developed a deep friendship. T.T. subsequently joined Green, but in 1995 he agreed to return to the Rangers as my deputy at the 2nd Ranger Battalion. Now, eight years later, I was again benefiting from his experience and unshakable values.

The TF 714 senior enlisted adviser was Command Sergeant Major C. W. Thompson, a laconic former rodeo rider turned soldier, and a trusted friend. My aide-de-camp was air force major Dave Tabor, a young, humorously sarcastic, but veteran MH-53 helicopter pilot who'd flown initial operations in Afghanistan in 2001. Also on the trip was the deputy commander of Green, thenâLieutenant Colonel Austin “Scott” Miller. Bennet, Scott's boss, had wisely dispatched him with me on this first trip both to keep an eye on me and to begin shaping my perceptions of his unit. Scott did the latter superbly and would become a key figure in the years ahead.

Those four, along with my communicator, navy petty officer Vic Kouw, formed the core of the command team. Starting that fall, for 60 percent of any given day, I would be close enough to literally reach out and touch any of these men (or their successors). The command team would grow in size and evolve with personalities in the years ahead. We would share countless hours on every type of aircraft and would struggle together to shape the command. The bonds would grow deep.

The purpose of this first trip was to begin to establish my relationship with those TF 714 forces that were currently deployed and, also important, to see the situation in each location and to assess our requirements for the future. Although I had served in Afghanistan in 2002, I had not been to Iraq, and I knew my view from the Joint Staff had been distant and incomplete. As always, I wanted to see the battlefield for myself.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

L

ike most things in Iraq that looked stable and orderly from a distance, the Republican Guard palace in Baghdad was, upon closer inspection, a mess. The American-led coalition had turned the palace into its headquarters following the March invasion, and on Friday, October 24, 2003, it was the first stop on my first trip as TF 714 commander to the theater in which my forces were most heavily deployed. The palace lay deep within the Green Zone, the

four square miles staked out as a sanctuary for coalition civilians and military forces on the western bank of the Tigris River, which bisects Baghdad. With Dave Tabor, we drove from BIAP west of the city along a road that the Coalition then called Route Irish. The drive was uneventful, the roadway not yet the notorious shooting gallery it would become a few months later. As we approached the Green Zone, over the tops of the palms that lined the driveway to the palace we could see the outlines of the huge busts of Saddam that perched on the facade. In each, the deposed dictatorâwhom we had yet to captureâwas refigured as a vintage Arab warrior. His cold, jowly face peered down from within a pith helmet and kaffiyeh, apparently worn by the Iraqis who rose against the Ottomans. Iraqi cranes hired by the Coalition had not yet ripped the

busts from their perches, and the palace had largely survived the initial bombardment of Baghdad in the opening hours of the war. On the outside, its beige outer walls conveyed an air of order and calm. Inside was a different story.

Over the summer, the initial postinvasion elation of April and confidence of May had quickly muddied, turning to growing unease in June. By August, nervousness tempered the halls and offices of the Pentagon. Data foretold more unrest and more violence that autumn. But there remained a hope, if only a halfhearted one, that if we could just find Saddam and get the lights on in Baghdad, the country would straighten itself out.

Following the March invasion, the Bush administration had eventually assigned Ambassador L. Paul Bremer to reconstruct Iraq after its rapid defeat and the collapse of Saddam's regime. As the head of the newly created Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), Bremer was responsible for governing the country with the objective of rapid transition to Iraqi sovereignty. The CPA had been using the palace as its headquarters for five months, but inside it felt like confused entropy.

The whole coterie of professionals, soldiers, contractors, and wide-eyed “augmentees”âsome of them twentysomething political operativesâseemed as if they had either arrived just hours earlier or they were about to be overrun by the proverbial barbarians beyond the gate. Boxes of documents lined some hallways. Those working in the palace had partitioned the cavernous Italian-marble rooms into offices using plywood. Some sat at imitation Louis XIV chairs and desksâwith gilded, curved legs and turquoise cushionsâleft behind by the Iraqis. Many on the staff looked aimless. I was amused by those who wore what I called their “adventure clothing”âhiking boots, earth-tone cargo pants, and Orvis shirts with multiple Velcro pockets purchased with the allowance many had been given to stock up for their tour.

That day I was there to meet Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, one of the newest three-star generals in the Army and the top military commander in Iraq. I had met Sanchez a few years earlier, and this time, in his Baghdad office, we shared a courteous rapport. In desert fatigues, he looked out from big rectangular eyeglasses.

“Your guys are doing what we need them to do,” he said.

But he left it at that. He did not slap a map down on the coffee table and explain what he was trying to accomplish and how our forces could help. His reticence was natural. TF 714's relevance to Sanchez was probably unclear. At that moment, we were tasked with capturing or killing the high-value former Baathist leadersâa set known colloquially as “the deck of cards” after the Pentagon had printed packs of playing cards with the grainy photographs and names of the top Baathists and distributed them to soldiers before they rolled across the Kuwaiti border.

The previous summer, our units had been key in the fight that killed Saddam's sons, Uday and Qusay, but we had not yet captured Saddam himself, the ace of spades. Sanchez had a lot to worry about in the fall of 2003, and I sensed that he did not know whether I would just be another of the countless visitors who appeared on his calendar every few months, or whether I was committed to becoming a real partner. We never got much beyond pleasantries, and I had no sense of the big direction of the war. Elsewhere in the palace, I met with the chief of staff of the CPA and second-highest ranking civilian in Iraq, Ambassador Patrick F. Kennedy. I explained to him what TF 714 was.

I arrived with some prejudice about the uneven and often unserious national resolve to make hard decisions in the months after the invasion. Many agencies were at fault for that, but the atmosphere in the palace added to my doubts about the CPA. Certainly many smart people worked hard to overcome great odds that summer and fall. But seven months of spotty progress had left many cynical. Policies kept them cloistered behind the palace walls, where they often worked alongside unqualified volunteers whose tour lengths were far too short to gain adequate, let alone advanced, understanding of the complexities of Iraq. The CPA ordered fundamental challengesâthat would affect the lives of Iraqis and the Americans fighting among themâto be tackled by spectacularly unqualified people, like a twenty-five-year-old with no financial credentials responsible for

rebuilding the stock market. I left the palace that day thinking,

Holy shit

.

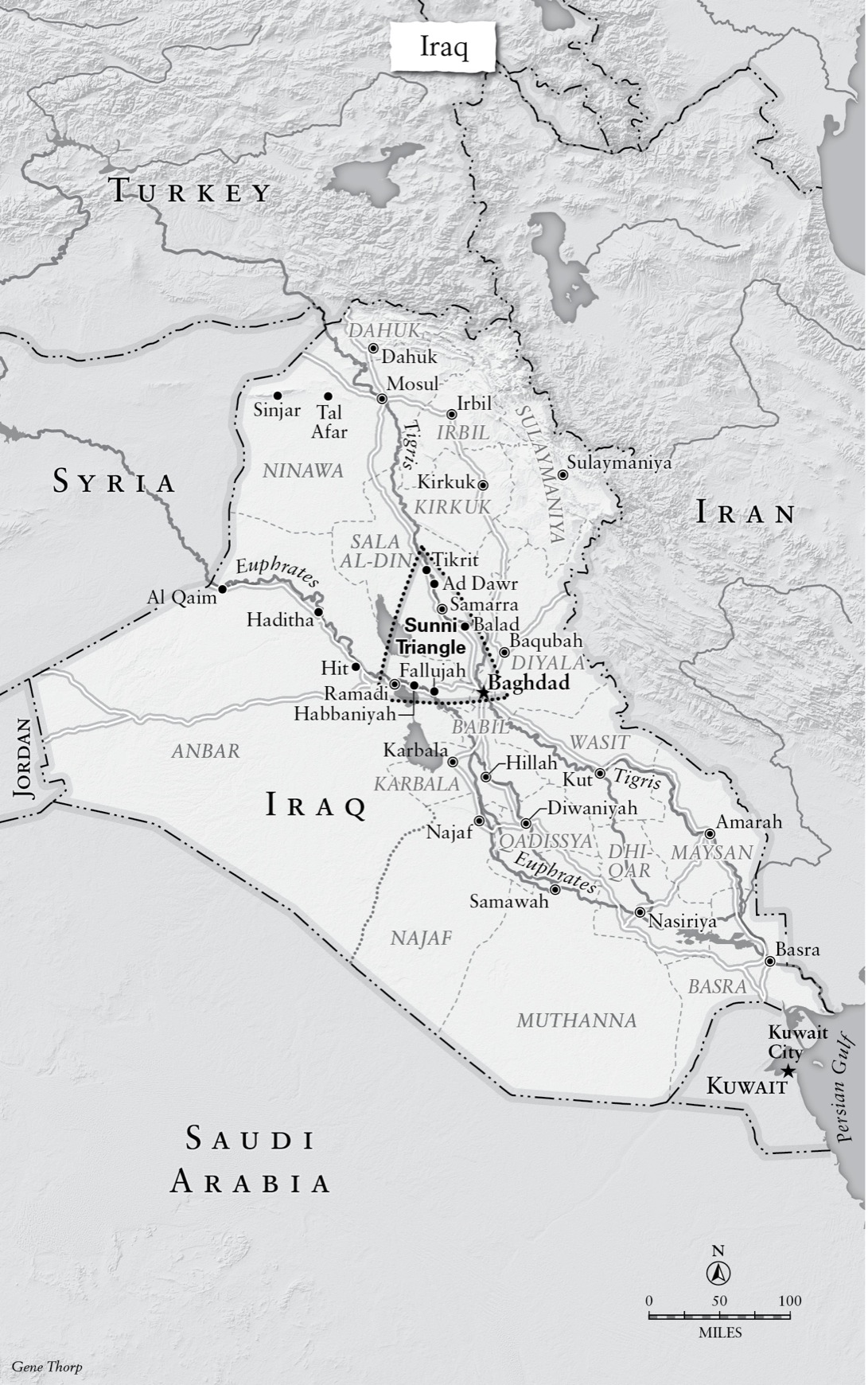

The next morning, October 25, I helicoptered with Dave Tabor and Scott Miller to Mosul, 250 miles upstream of Baghdad on the Tigris. The second-largest city in Iraq, with some 1.8 million people, Mosul was the responsibility of thenâMajor General David Petraeus. His 101st Airborne Division had fought up from Kuwait through southern Iraq and into Baghdad, at which point they had been moved north. The city sat where the Arab and Kurdish regions met uneasily, with the Sunni Arabs predominantly in the traditional city center south and west of the Tigris and the Kurds in suburbs to the northeast.

In a former palace overlooking the city, Dave Petraeus was full of energy, as always. His office was a huge, marble-floored room turned into a warrior's den by the combat gear hanging on hooks and the cot he slept on, covered with the camouflage poncho liner issued to every soldier. Dave and I had shared an early fascination with irregular wars and the counterinsurgents who had fought them in Indochina and Algeria. As effectively as any commander at the time, Dave had read the situation in his area of Iraq, recognized the tremendous threat of instability, and moved rapidly to seize the fleeting opportunity to forestall it. He made early progress by spending energy and money on economic and political development. His force established governing councils, opened schools, and corralled, equipped, and dispatched a local Iraqi security force. But when the twenty thousand soldiers of the 101st turned over Mosul to an American unit

only a fraction of their size the following January, the insurgents soon destroyed what calm Dave's force had been able to win.

TF 714 had a small detachment working in Mosul in conjunction with Dave's division, and we enjoyed his strong support. Still, when I reviewed with our team how they ran targeting missions periodically, based on the trickle of tips and intercepts they were able to scrape up in the early days, I was convinced they were having limited effect. In October 2003, Saddam and his network of former regime members remained our primary focus, but at this point the picture we could draw was very rudimentary. Rare bits of intelligence came from the task force headquarters in Baghdad or from the other outposts throughout the province. They were working hard to understand the people who lived in the big city down the hill from their compound and were accomplishing as much as a team of sixteen could. But they were largely cut off from the rest of our force. I thanked them for their work and went to the helicopter pad feeling that despite their talent and dedication, the team's isolation limited their ability to contribute effectively. The price of that isolation was made clear on the airlift down to Tikrit.

As we flew single file in two Black Hawks, our helicopter suddenly took a sharp, aggressive turn, banking hard off course. We tilted sideways, bringing the desert rushing below us into view through the open side doors. As we circled up and back, the pilots said over the headsets that the helicopter behind us had been shot down, clipped by a rocket-propelled grenade. Thankfully, before leaving for Mosul, I had

left my key TF 714 staff behind in Baghdad to draw up a campaign plan for the upcoming operation in Afghanistan that John Abizaid had requested. Therefore, the second of our two UH-60s, originally meant to be full of the planning staff, was empty except for the crew. It was further fortunate that the craft did not instantly explode when hit. We landed near where it had made a hard landing, unloaded all of the crew, and took off as the downed helo burned, hissing and popping as each piece exploded off. One of the pilots, with a leg wound already bandaged, joined our helicopter. In the air, I asked him how he was.

“I'm pissed off, sir,” he said through the headset. “Goddamn it.” He leaned over, looking back at the smoke. “They shot down my helicopter.” I smiled, and after a few moments he continued. “Sir, you don't remember me, but I was a Ranger in 2nd Rangers for you.” I hadn't recognized him in his flight suit and helmet. We reminisced, and I was reminded how small our special-operations world was. And I was reminded of the resilience of its ranks.