My Share of the Task (18 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

As we continued to Tikrit, I turned my thoughts to our enemy. I tried to picture the man who had bravely shot at us and what had brought him out to the desert to do so. He would have needed a certain level of commitment to stand in open ground, in broad daylight, and take a potshot at two heavily armed Coalition helicopters. Surely, in that area of Iraq and at that time, he was Sunni. But what motivated him? With the accuracy of his rocket, was he a disenfranchised Baathist soldier? Or was he younger and more devout than his Baathist counterparts, taking orders from Ansar al-Sunnah, an Al Qaedaâallied jihadist group with a presence in that region? Contrary to

the administration's official line, the attack did not, to me, smack of desperation. It seemed to signal, “Game on.”

On landing on the hard-caked helipad, we moved to another of Saddam's mansions, which thenâMajor General Ray Odierno was using for his headquarters. Ray and I had grown close at the Naval War College. His son Tony, now an infantry lieutenant, had babysat Sam often, and we had shared more than a few beers after weekly Hash House Harrier runs. Now he commanded the 4th Infantry Division, a brigade of which my father had led in Vietnam before serving as its chief of staff. Ray met us in the colorful, cavernous foyer. He knew we had lost a helo but not any men.

“Stan.” He reached his big hand out, his baritone filling the high-ceilinged room and echoing off the chamber's hard marble walls and floor. “Heard you had an exciting trip in.”

Ray was responsible for Tikrit, the northernmost of the three cities that, with Ramadi out west and Baghdad in the center, formed the Sunni triangle, where the insurgency would rage. He described the situation as serious. Tikrit was Saddam's hometown, and he was thought to be hiding within its limits. High-level Iraqi officers had returned to the surrounding province, a

Sunni stronghold, after the invasion. Some journalists concluded that Ray had failed where Dave succeeded. Cerebral Dave fought with money and good governance, the story went, while Ray, the bald, towering lineman, was blunt and brute and alienated the population with huge sweeps and arrests. Reality was less clear cut. Ray's physical presence belied a nuanced approach to the complexity he was encountering. Tikrit was different terrain from Mosul, and both cities would host bitter fighting in the years ahead. Like Dave, Ray appreciated the work of our small team that was linked up with him. But I quickly saw our main obstacle. Without real-time links to an effective TF 714 network, the team's good relations with their 4th Infantry Division hosts wouldn't mean much.

Like the team in Mosul, the force in Tikrit largely toiled away on its own, with inadequate support or guidance. Like the wider Coalition effort, TF 714 suffered without a common strategy or a network to prosecute one. This was most glaring in the way we handled raw intelligence, a significant amount of which came out of the raids that the TF 714 operators conducted throughout Iraq and Afghanistan. On each mission they found documents and electronics, as well as people who knew names and plans that we wanted to know. But human error, insufficient technology, and organizational strictures limited our ability to use this intelligence to mount the next raid. The sole intelligence analyst in Mosul or Tikrit was unable to digest the information brought back in dumps by the operators to the outstations in the early hours of the morning. The teams were ill equipped to question suspected insurgents they found on the targets or detained briefly at their forward bases. And they could not easily seek assistance from Baghdad. We considered our communications robust for a small element, but we quickly found them inadequate for sending and receiving the vast amounts of classified information to and from Baghdad fast enough to make it relevant to targeting. Single e-mail messages went rapidly, but modern intelligence depended upon large volumes of dataâscanned images of maps or documents, videos found on computers and camcordersâwhich required significant bandwidth. Without the ability to share these quickly, we were hamstrung.

These strictures led the force to adopt a standard practice that summer and fall that looks farcical in hindsight. After the teams in Mosul or Tikrit or Ramadi digested what little they could from the captured material, they filled emptied

sandbags, burlap sacks, or clear plastic trash bags with these scooped-up piles of documents, CDs, computers, and cell phones and then sent them down to our base in Baghdad. Some bags started the trip with a yellow Post-it note on the outside explaining their origin; others didn't. Detainees thought to be important made the trips with the bags.

Fundamentally, the senders and receivers, in this case the forward team and its higher headquarters, had neither a shared picture of the enemy nor an ability to prosecute a common fight against it. This inspired territoriality and distrust. Outstations rarely saw the benefits of the raw intelligence they collected, which often disappeared into a black hole once they sent it up. Equally frustrated, the analysts on the receiving end often had little context for the bags' contents or the detainee's identityâeven when the sticky notes didn't fall off in transit. They had little indication of whether the hard drives or documents came from a mansion owned by an old Baathist or had been found underneath prayer rugs at a jihadi safe house.

When I inspected our intelligence-processing facility at BIAP later that month, I opened a door to a spare room to find it filled with piles of these plastic and burlap bags stuffed with captured material. They appeared unopened.

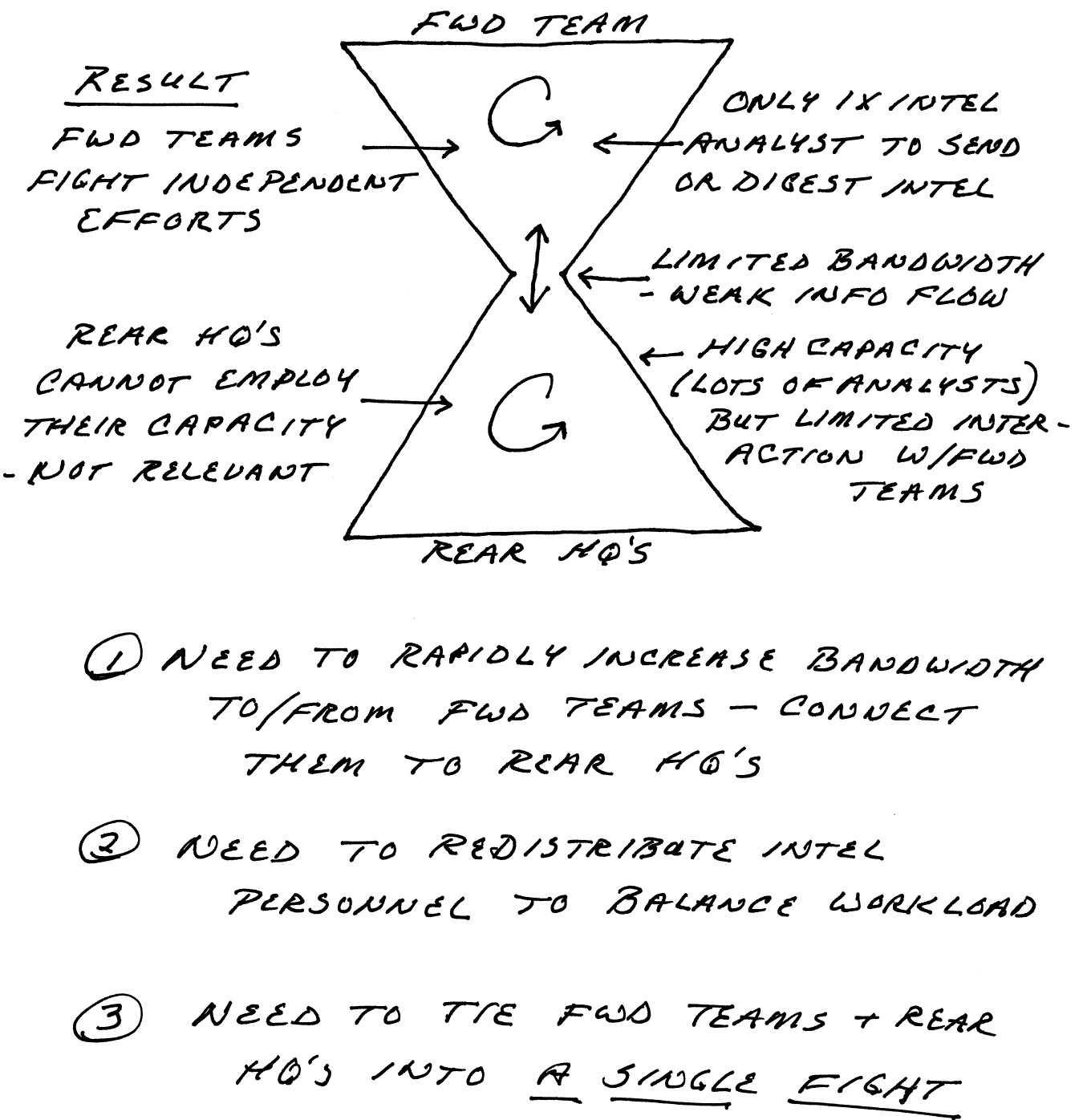

I returned to Baghdad that evening itching to put my thoughts down on a whiteboard and to hear what everyone else had observed. This is how I do my best thinking, and it was the first of many such collaborative sessions. Talking with Scott Miller, I drew an hourglass. The top triangular half represented a forward team, the bottom was the rear headquarters. They met at a narrow choke point, allowing for only a trickle of interaction between the two.

“Would removing this half affect the forward team?” I asked, putting my hand over the bottom triangle.

From what Scott had seen, he said it wouldn't. The rear headquarters were not relevant to the forward teams, as each was fighting an independent campaign. At the very least, targeting a terrorist network was both tedious and violent; starving the teams of information, as we were in the fall of 2003, made the fight sluggish and excruciating. The hourglass diagram portrayed a simple defect in our force's structure. I copied the sketch to a legal pad and left Iraq for Afghanistan with the rudiments of the vision that would drive TF 714's change for the rest of my command.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

O

n October 27, two days after we left Baghdad, Zarqawi's group ushered in Ramadan with the latest in a line of its strategic bombings. That morning, an explosion outside the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) building killed two of its staff and ten Iraqi bystanders. This was the latest in a pattern, although its significance was not then apparent. It began on August 7, when a bomb in a car parked outside the Jordanian embassy in Baghdad exploded, killing seventeen and wounding forty.

Two weeks later, at 4:30

P.M.

on August 19, a suicide bomber driving a

KAMAZ flatbed truck laden with military-grade munitions breached the front gate at the United Nations headquarters in Iraq, detonated the cargo in front of the facade, and collapsed part of the three-story building. Among the twenty-two victims who died was Sergio Vieira de Mello, the head of the U.N. mission in Iraq and a famed expert in postwar reconstruction. The blast also killed Arthur Helton. I had known and liked Arthur from my year at the Council on Foreign Relations in 1999, when I was a colonel and he was the new director of its peace and conflict program. After a second bombing targeted the remnants of the mission on September 22, the U.N. withdrew all but a handful of its staff to Qatar. They wouldn't return in force until late 2007.

Although it was unclear at the time, these attacks against humanitarian organizations proved to be part of Zarqawi's incipient strategy to isolate the Americans and shape the battlefield. Zarqawi clearly hated the Jordanian government, so unalloyed vengeance may have been at play. He blamed the U.N. for giving Palestine “as a gift to the Jews so

they can rape the land” and, according to one of the operatives responsible for the attacks, he sought revenge against Vieira de Mello for having helped dismantle an Islamic nation through his work

during East Timor's independence. But the real logic to the violence was less histrionic. With the U.N. and ICRC gone, Zarqawi eliminated two organizations that had the experience and niche capacity to help reconstruct Iraq. Perhaps more important, as the war became one of perceptions, by scaring away the U.N., the Red Cross, and other international organizations, Zarqawi ensured that Iraqis increasingly saw only American troops in the streets.

The American efforts to cobble together a wider coalition were largely undone in a handful of explosions. As the months progressed, it looked much more like an American occupation than an international effort.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

M

eanwhile, in Afghanistan, our forces were planning what we jokingly referred to as General Abizaid's “big-ass operation.” The final plan would send a large number of TF 714 forces into eastern Afghanistan, where intelligence reports had placed senior Al Qaeda leadership in the remote crannies of Kunar and Nuristan provinces. Abizaid knew that American presence thereâand in fact across all of Afghanistanâwas stunningly thin. He could not raise the overall troop numbers because of

a cap attributed to Secretary Rumsfeld, so he ordered a temporary surge of TF 714 forces because of our unique agility.

The American military's normal process for moving troops in and around theater was bureaucratic in design and cumbersome in practiceâalmost the polar opposite of what we now needed. We realized that for TF 714 to execute with the speed and precision this campaign demanded, only a new construct would do. Fortunately, my predecessor, Dell Dailey, had taken a

critical step to secure authority for TF 714 to reposition forces without the traditional staffing. It was a farsighted move that proved invaluable.

In November, I was back in Afghanistan for the final days of planning and then implementing what by then was named Operation Winter Strike. Although like most soldiers I was most comfortable when immersed knee deep in the tactical details of an operation, as much as possible I left the planners alone. As Bill Garrison's leadership had taught me, displaying trust and instilling a sense of ownershipâand the confidence that comes from itâamong the soldiers on the ground was almost always more important than any slight tactical tweaks I might make.

As Winter Strike approached, I moved into an office at the back wall of the tent. The operation would demand long days, so initially I put my rickety aluminum cot next to my desk and encouraged others to do the same. I had watched commanders who remained aloof from their units' actual operations, and I had long ago decided that wasn't right for me. But that was only the first in a long chain of small decisions and tweaks. I had to take into account not only our mission but also the team around me and the tools, like communications and aircraft, at our disposal.

Within weeks of assuming command, I appreciated the complexity of TF 714's task, its geographic dispersion, and the array of relationships we needed to maintain in order to succeed. All of this convinced me that I needed to leverage technology to be able to exercise full command, whether forward in Iraq or Afghanistan, or back in the United States.

Our dispersion also drove us to try different distributions of key leaders across our network. After some trial and error, we spread our three flag officers among our main centers, with one each in Afghanistan, Iraq, and our headquarters at Fort Bragg. Although over the next two and a half years I grew close to my two assistant commanding generals, Dave Scott and Bill McRaven, we weren't able to be physically together in the same room until April 2006, a month before they were promoted to new positions outside TF 714.

The technology and team around a commander were keys to the unit's success, but the command style still depended heavily upon the leader's personality. By nature I tended to trust people and was typically open and transparent with colleagues and subordinates. By providing them tremendous latitude, I believed I accessed greater intellect and judgment. Inclusiveness also instilled a shared sense of ownership, which reduced the danger of my becoming a single point of failure. But such transparency could go astray when others saw us out of context or when I gave trust to those few who were unworthy of it.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

W

hile tactically smooth, Winter Strike failed to yield any top Al Qaeda affiliates. Although we already knew slow, ponderous sweeps were no way to target terrorists, the operation confirmed my hunch that the authorities that provided TF 714 with increased flexibility, were brilliantâbut slightly flawed. We needed its proposed web of teams and the preapproved authority to reposition them to respond to emerging threats. But the forces that would respond couldn't be back in the United States waiting for the call. The distance and the necessary bureaucratic deployment approvals would make them too slow and would cause them to lose focus. We needed small nodes, tightly linked together and with an unprecedented ability to act locally. Those local teams would need to be able to make decisions far from the center and would require a network that rapidly marshaled resources, information, and support. To get there TF 714 would need to develop better intelligence.