My Share of the Task (43 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

Toward the end of November, I sat and listened to M.S.âwhose relentlessness and poise had been fundamental to the final stages of the Zarqawi hunt six months earlierâas she spoke in front of the whiteboard in a small room Task Force 16 used in the back of the bunker at Balad. In a series of raids that month, Task Force 16 had captured most of

Ansar al-Sunnah's leadership, including at least ten of the organization's topmost leadersâthree national-level administrators, a founder of the group, and seven geographic emirs from Al Qaim to Baqubah to Tikrit. Pointing to a diagram of the enemy's network, M.S. described each capture and the cumulatively crippling impact to the organization.

To be convinced to reconcile, an enemy organization normally has to think it's losingâor at least be convinced it cannot win. Decapitating the leadership of the organization, as we had just done, went a long way toward doing that. Graeme soon made these leaders, now in our custody, a focus of his efforts. Among other things, Graeme sought to slip a wedge into the fissure between Ansar al-Sunnah (AAS) and AQI.

After offering sanctuary to Zarqawi and other Al Qaeda operatives who fled the American bombing runs in Afghanistan, AAS had adopted many of AQI's tactics during the insurgency, including beheadings and wanton killing of civilians. Closest to home, two years earlier AAS had dispatched the Saudi suicide bomber into the

mess-hall tent in Mosul. For years, Al Qaeda in Iraq had sought to formally bring Ansar al-Sunnah under its control. But, leery of Zarqawi, the group's

Kurdish leaders had reported through back channels to Al Qaeda's leaders that Zarqawiâimpious and power hungryâwas not the man in propaganda reels, and that they had made a terrible choice staking their fortunes on him. Despite these persistent tensions, rumors had surfaced again that fall of a potential

merger between the two groups.

Graeme initially focused his time on a detainee, the religious emir of Ansar al-Sunnah, a man named Abu Wail. Every ten to fourteen days, Graeme had Abu Wail brought out of detention to talk with him. Graeme made sure the emir was allowed to change out of his orange jumpsuit, cleanse himself, and put on Iraqi robes. The guards would bring the emir into the room, unshackle him, and leave him alone with Graeme, who would be preparing tea to serve to the emir. As the door closed, a primal electricity would fill the small room, or even the larger Maude House salon where they met. In any other moment or place, the two men sitting there, separated by a table and two small glass cups of hot golden tea, would have attempted to kill each other. It was this mutual recognitionâthat Graeme had spent most of his life hunting men like Abu Wail and that, given half a chance, the emir would saw Graeme's Scottish head offâthat allowed them to have a conversation. Hard recognized hard.

These were conversations that no United Nations technocrats or State Department diplomats, no matter how skillfully schooled, could have had.

At the end of their conversations, the emir would be taken back to detention until their next meeting. Slowly, somewhat impossibly, a respect built that would later pay off. Toward the end of their meeting early that December, the emir addressed Graeme.

“You know,” he said matter-of-factly, “you're a force of occupation, and don't try to tell me differently. That's how we see itâand you're not welcome.” He explained to Graeme in his deliberate way that his guidance from the Koran was that he must resist the force of occupation for yearsâfor generations evenâif it threatened the faith and his way of life. He paused, as Graeme continued to listen. “We've watched you for three and a half years. We've discussed this in Syria, in Saudi, in Jordan, and in Iraq. And we have come to the conclusion that you do not threaten our way of life. Al Qaeda does.”

It was a remarkable breakthroughâand opened up possibilities for what effect the emir might have if freed. So during the final days of December 2006, when news from Iraq was dominated by the bungled hanging of Saddam Hussein, the Coalition released Abu Wail from prisonâ

FSEC's first strategic release. They released him without conditions. We needed him to be a credible member of Ansar in order to stir their thinking and divert their direction. Requiring him to meet with a westerner or to spy for us would put that in jeopardy. Regardless, we worried suspicious comrades might well kill him.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

“

A

nnie, another Christmas apart,” I wrote to her by e-mail. I was to spend the day in Afghanistan with our force and then after dark fly in one of our aircraft to Balad, arriving after midnight. Christmas Day was spent seeing parts of my force in Iraq, while Annie, with Sam home from college, followed their tradition of Christmas Eve dinner in a local Chinese restaurant. This was the third Christmas in a row that I was gone, and while she wasn't alone, it had to be lonely.

“We never really expected this kind of thing at this stage in our lives,” my e-mail continued, “but I still believe we are doing what is our dutyâas a teamâto the nation and to the people we serve with. You know the frustration I feel when I see the packed malls and overfed greed of so many Americans. But when I meet in small posts in harm's way with young Americans who believe in their cause and their dutyâand who desperately need to see leaders who reflect the values and dedication they want in the people they followâit is pretty easy to stand the separations with the quiet confidence we are living up to all the values we were raised to uphold.”

My thoughts were as much for me as they were for her, but Annie always seemed to understand what I was trying to say. For me, it meant staying forward deployed. And as hard as it was for her, Annie wouldn't have had it otherwise. It was fundamental to the kind of leader I believed I should be. Being apart so long was painful, and she worried. But she was proud of me, and that meant everything.

By the time I wrote to Annie and thousands of other soldiers sent e-mails home or called families who missed them, President Bush had decided on a

new strategy in Iraq, following months of review

stretching back to the spring. During Christmas and the final days of 2006, he weighed the heavy decision of how many troops he would “surge” to Iraq as part of this new way forward. He eventually decided to send five army brigades that would primarily focus on Baghdad, and two Marine battalions to reinforce Anbar. The war in Iraq was about to hit an even higher register.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

O

n the cusp of this expansion in Iraq, pressing developments on a different continent demanded my attentionâand drew me to Addis Ababa.

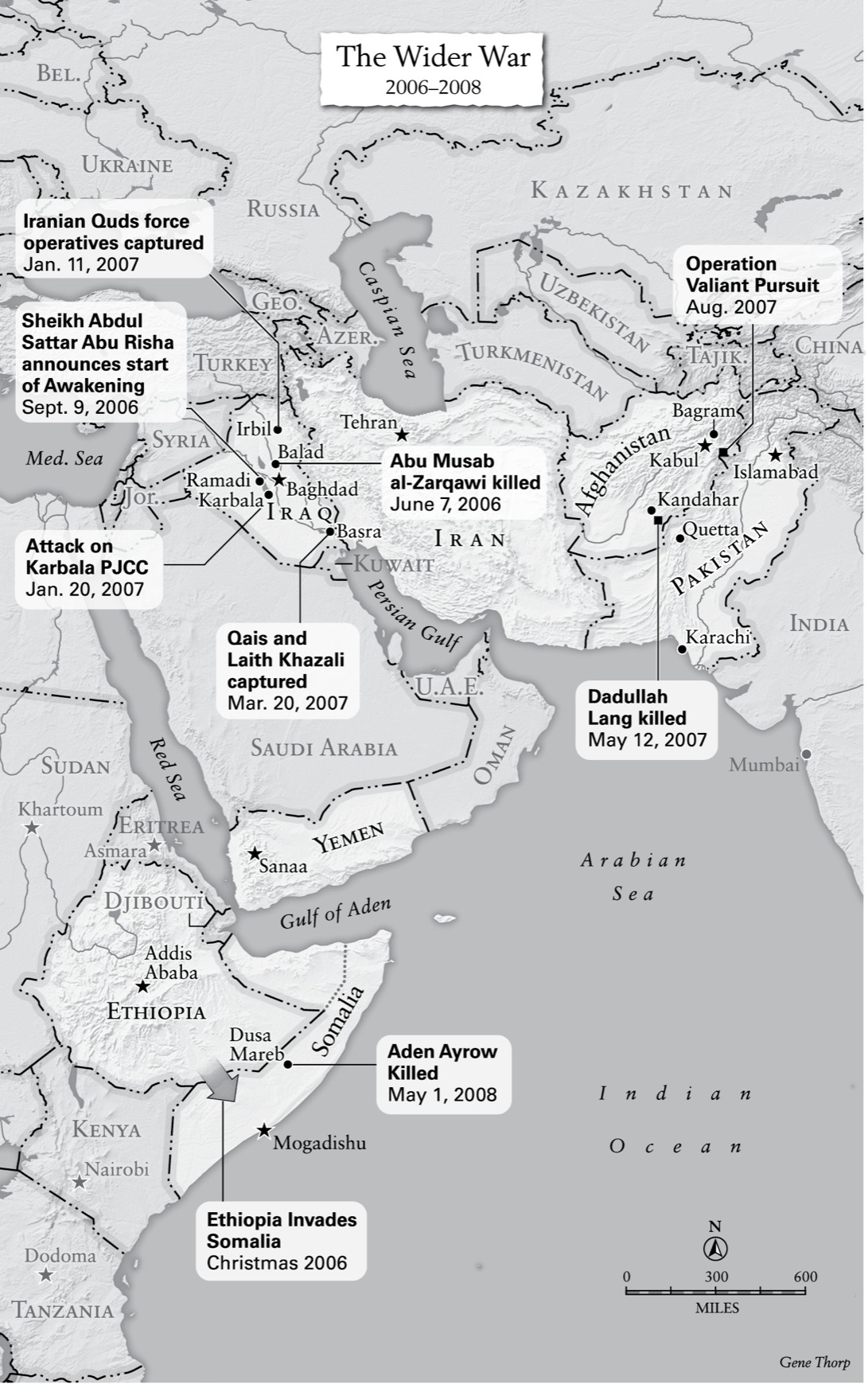

On Christmas Eve 2006, Ethiopian troops had invaded neighboring Somalia, then riven by a civil war. Six months earlier, in June, the Islamic Courts Union, an umbrella group of Sharia courts and Islamic militant groups, claimed control of Mogadishu and most of southern Somalia. One of the main militant groups of the ICU, Al Shabab, or “the youth,” had developed increasing ties with Al Qaeda, largely through its charismatic founder, Aden Hashi Ayrow. We

believed Al Shabab was sheltering some of Al Qaeda's senior operatives, including

Abu Taha al-Sudani, leader of Al Qaeda in East Africa, as well as a number of those behind the 1998 embassy bombings.

Although the Ethiopian operation was not a huge surpriseâthey invaded to suppress an insurgency they thought threatened eastern EthiopiaâAmerican policy was poorly postured for what looked like a potential opportunity. As the Islamist rebels were forced to flee the Ethiopian forces, Al Qaeda operatives, on the run, would be more vulnerable and perhaps come into view long enough for us to target them.

With a small number of intelligence-collection assets, and the periodic assistance of American aircraft and ships, U.S. forces targeted the Al Qaeda leaders we could pinpoint, and pressured the others. It was sensitive, difficult business due to our limited access into Somalia. Over the coming months, the United States expanded its capacity to both find and target Al Qaeda leaders in Somalia who had previously eluded us. As the United States relied on a good rapport with the Ethiopians, my team and I visited Addis Ababa repeatedly to do the slow, deliberate work of building a relationship with them. Most instructive for me, as my position increasingly required forging partnerships with other countries, was the Ethiopians' frank skepticism toward U.S. intentions and reliability, echoed on my trips to Islamabad and Sanaa.

These trips, sometimes to Addis Ababa and back in a day, were typical of the final two years of my command. The constant movement around the region was often choreographed down to the minute. My command teamâwhich evolved as original members were promoted to new jobs and replaced by men of equal talentâspent flights hunched over e-mails on their Toughbook laptops, talked through secure in-flight voice links and VTCs to headquarters on the ground, wore civilian clothing, and kept Ambien close at hand. From the look of our group as we'd gather preflight in the dark outside the SAR or stumble back in, exhausted, a few days later, our travels came to be known as the Pain Train.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

J

ust after 9:00

P.M.

eastern time on January 10, 2007, President Bush stood at a podium in the White House library and spoke frankly about the course of the war in Iraq. He admitted the many challenges the mission faced and announced a “new way forward.” Bush described the way in which troops would change how they operated, embracing counterinsurgency tenets. Most controversially, he announced that he would surge nearly thirty thousand troops, most of them to secure Baghdad. It was a courageous decision taken at a time when currents of opinion were flowing strongly in the other direction.

The physical impact of these troops on Baghdad, and all of Iraq, would become clear only in the months ahead. But by the time these troops began to arrive early that spring, Iraqis had experienced nearly four years of violence and uncertainty and were, by and large, exhausted.

For Sunnis, the future was fraught with danger. Fearing the disenfranchisement that came with Saddam's fall, de-Baathification, and the emergence of an Iranian-influenced Shia-majority national government, many had joined an insurgency increasingly dominated by Zarqawi's extremism. At first, they thought they could succeedâexpel the Americans and reclaim rule of Iraq from the Shia. But after years of struggle, prospects for doing so looked bleakâand with the increasingly vicious onslaught by the Shia militias, the U.S.-led Coalition appeared less like an enemy and more like a necessary protection against the Shia death squads and a vital arbiter in the struggle for power in Iraq. The emerging Sunni awakening movements reflected this calculation, and America signaling its commitment with the surge reinforced it.

The size of the surge force was no more important than its quality. By late 2006, the U.S. forces were the best we had yet put on the field. The troops in, or returning to, theater were increasingly experienced and wise. They included commanders like Sean MacFarland and Mike Kershaw, whose brigade ultimately tamed the Baghdad suburb of Yusufiyah, the southern belt that had been an AQI sanctuary.

Against all of these positive intangibles, however, we as a nation and a force were undeniably tired as well.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

D

uring his televised address to the nation in which he announced the “new way forward” in Iraq, Bush spoke provocatively about the threat posed to the Iraqi project by Iranian proxies. “

Succeeding in Iraq also requires defending its territorial integrity and stabilizing the region in the face of extremist challenges,” he said. The Syrian and Iranian “regimes are allowing terrorists and insurgents to use their territory to move in and out of Iraq. Iran is providing material support for attacks on American troops. We will disrupt the attacks on our forces. We'll interrupt the flow of support from Iran and Syria. And we will seek out and destroy the networks providing advanced weaponry and training to our enemies in Iraq.”

For nearly three months, TF 714 had been targeting the Iranian proxies President Bush spoke of. The previous fall, General Casey had asked us to start targeting specific Shia extremists, particularly Iranian-backed “Special Groups.” At the time, as Robert Gates explained that winter,

there were four vectors of violence in the country: attacks from the Sunni insurgency directed at the Coalition and Iraqi government; terroristic attacks by Al Qaeda against Shia and western targets; sectarian conflict between the Sunni and Shia; and Shia-on-Shia violence, largely nonideological power struggles in southern Iraq.

Shia organizations like Jaish al-Mahdi, or JAM, tiptoed along a line of opposition to MNF-I and made an uneasy truce with the status quo. Beneath the surface, however, were more sinister elements supported by Iran's secretive Quds Force. These elements operated an aggressive, seemingly unconstrained network that funneled material, including the

explosively formed projectile IEDs, known as EFPs, that were devastating Coalition forces. They also provided training and advice to Iraqi Special Groups.