My Share of the Task (39 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

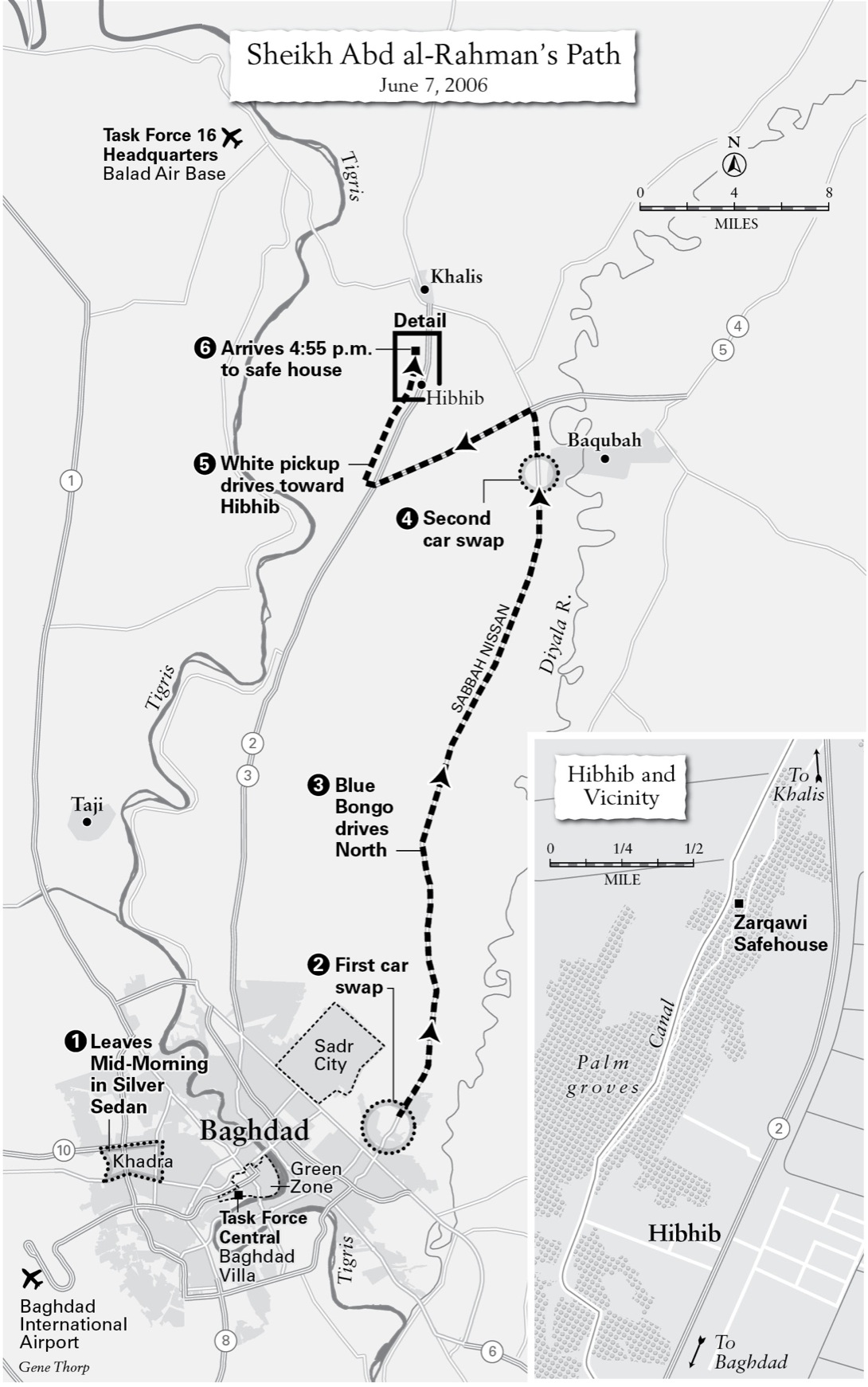

The roused operators, who had returned to the villa and shed their equipment only a few hours earlier, soon joined J.C., Tom D., and the rest of the intel team in the JOC. They also called up to TF 16 headquarters at Balad. Steve, the task force commander, and M.S., its intelligence chief, were in the O&I VTC when someone came in and told them Abd al-Rahman was moving. They came out into the JOC and watched a replay of the feed showing the vehicle swap. The feeds went onto the JOC screens, and Steve started pulling in more ISR assets from across Iraq.

A few minutes later, Steve came into my office on the other side of the plywood wall. He was businesslike, but this wasn't business as usual. As I listened, I knew the frustration he had experienced as a squadron commander over a year earlier, when lost surveillance had let Zarqawi slip through his fingers.

“Rahman's moved, sir. He swapped vehicles and left Baghdad,” he said.

“Okay. Where's he going?” I asked. I assumed he would head to Yusufiyah.

“He's going north. We're pulling in assets to cover this guy.”

“Really?” I said, surprised at the direction. “Okay. Don't spare anything.”

“Roger out,” Steve said. He returned to the JOC, and I stayed in my office.

On the screens in both the JOC in Balad, and down with Tom D. and J.C. in Baghdad, they watched the Bongo continue up Sabbah Nissan. I came out a couple times to look at the feed. The JOC was buzzing. Normal operational coordination continued, but most kept an eye on the Bongo truck on the screen.

A little less than an hour later, Abd al-Rahman pulled into the capital city of Diyala Province, Baqubah. It was now late in the afternoon. The city the Bongo truck had entered had a mixed Sunni-Shia population of about five hundred thousand. The Sunni insurgency was deeply entrenched in the province around it, where

Al Qaeda enjoyed alarming support. In the previous days, four Shiite mechanics had been gunned down, six Iraqi policemen had been attacked, and the heads of eight Sunnis had been found

together in banana crates. Four days earlier, at a fake checkpoint on the road into the city, insurgents had killed twenty Shiite bus passengers, including seven students preparing to

take their final exams at a university in Baqubah.

The Bongo pulled off the street into a parking area in front of a building, apparently a restaurant, in a commercial part of town. Abd al-Rahman got out and went in, past a figure who appeared to stand watch on the curb. A minute, maybe two, later, a pickup truck pulled into the lot. It parked nose to nose with the blue Bongo truck. This struck everyone as odd. After the kicked-up dust settled, the pickup's coloring came into viewâwhite with a red stripe. The JOC froze. They had seen that truck before or, rather, dozens like it. Zarqawi used a fleet of white pickups with red stripes, part of an unnerving countersurveillance shell game. Five or six white pickups would pull up, he would hop in one and climb through the cab to the next, and they would peel off in separate directions.

An odd figure emerged, dressed in full Gulf-like attire, with flowing white robes and kaffiyeh. He entered the building, walking past the guard without any visible exchange, as if they knew each other.

The Baghdad JOC was on edge.

Here he is, dropped off outside of Baghdad

.

This is it; this is

what we've been waiting for.

“What do you think?”

Tom D. asked J.C.

“No, no, hold on,” J.C. said. “This isn't it.” Not everyone there agreed.

He's in there, right now, meeting with Zarqawi

. But the meeting spot didn't feel right to J.C. Too congested. Too insecure.

Luck had slipped Zarqawi through countless checkpoints in the past two years. It had hidden him from our helicopters in Yusufiyah a few weeks earlier and had been there when our camera gyroscope locked up and spun out and lost him on the road between Ramadi and Rawah a year earlier. Luck helped every bomb that went undetected beneath a roadway or hidden behind clothing. But luck now swung to our side: Before we had to decide whether to move on the building, two figures walked out its front door.

No more than three or four seconds passed between when the two emerged into the sunlight from under the building veranda and when they got into the white pickup a few feet in front of it. In that time, both J.C. and one of his team members picked up his movements.

That's Rahman,

they said.

Follow him.

The white pickup with a red stripe, which had deposited the sheikh-looking man with the flowing robes, peeled away from the building. The car began to look like a shuttle, ferrying between this building and, inevitably, somewhere else.

Steve came in again and told me Abd al-Rahman had left Baqubah. It was now late afternoon, and the JOC beyond the plywood wall was loud. People were on phones, coordinating the ISR that Steve had pulled in and that was flying high overhead toward Baqubah. Soon we had six, and then nine, orbits stacked in the sky, watching four targetsâthe silver sedan still in Baghdad, the way station in Baqubah, the blue Bongo still parked there, and now the white pickup hauling out of town. We needed that many eyes, but we risked spooking the targets as the airspace became congested. Inside the JOC, Steve's team began to work out how it was going to go down.

What are we hitting? What is Baghdad saying?

The white pickup drove northwest out of Baqubah five kilometers to a small town identified as Hibhib, where it got off the main road. It passed through the sparse streets and continued onto a single-lane dirt frontage road, running alongside a narrow concrete irrigation canal half full of turquoise water. Dense groves of palm trees, with thick shrubs and undergrowth, extended back a few hundred meters from the track on the passenger's side. In the early-evening light, the groves were dark and shadowy. The truck approached a boxy two-story house tucked among the trees, sitting half a dozen car lengths back from the road at the end of a driveway. It had a carport under the front edge of the second floor. Only the beige facade of the house was fully visible, as the rear part of the building disappeared into the shadows and palm trunks that surrounded it.

At 4:55

P.M.

, the truck turned right off the frontage road and stopped halfway up the driveway, in front of a closed gate. While Abd al-Rahman stayed in the passenger seat, the driver got out and went to the driveway gate. A figure emerged from under the carport roof and walked down the driveway to meet him. After a short exchange, the second man went back to the house and then came back and opened the gate. Back in his white pickup, the driver pulled through the open gate and parked in the carport. Our team saw Abd al-Rahman get out and enter the house. The white truck reversed out of the driveway and went back the way it had come. As they watched this down in Baghdad, Tom D. turned to J.C. “What do you think, J.?”

“I have no reason to tell you not to hit it,” J.C. answered.

“I'm not going to promise you that's Zarqawi,” J.C. said, pointing to the screen. “But whoever we kill is going to be much higher than anybody we've ever killed before. So I'm saying, absolutelyâwhack it.” Inside, he felt, would be al-Masri, Zarqawiâor both.

Tom D. told his operators at Baghdad to go. Steve came into our SAR up in Balad. “We're launching Tom D.'s boys.” Down at Baghdad, the troop of Green operators suited up and waited for the helicopters to land in the front yard of their villa safe house.

Steve came in a few minutes later. “Sir, you've got to see this.”

We brought up the video feed on the screens in front of our U-shaped desk. Mike Flynn and Kurt Fuller were next to me. The video replayed Abd al-Rahman's arrival and the white truck's departure. Then he played a scene that had just occurred. On the video, a figure emerged from the shadow of the veranda and walked down the driveway. As he got into the sunlight, we could see more clearly. He looked heavy and was dressed head to toe in black. He walked past the gate and continued to the end of the driveway, where it met the frontage road going back to Hibhib. He stood, looked left up the road, looked right, and walked back to the house.

“That's AMZ,” I said, turning to Steve standing by the doorway.

“Yes, sir. We're going to bomb it,” he said.

Steve remembers my reaction being one of irritationâI'd hoped to get Zarqawi alive. I remember calmly telling him to do what he had to do. Having worked so closely with Steve, I'm confident his recollection is more accurate. We'd always planned to capture Zarqawi for his obvious intelligence value, but not at the risk of his escape. To give up that possibility was a difficult decision that had to be made quickly in response to the situation as it was developing, and Steve had the experience and authority to make the call. I'd made a point of, and we'd been very successful, trusting subordinates to use their best judgment. This time should be no different. I did not interfere.

There was good reason to strike. As Tom D. and his operators recognized, a ground raid would be difficult, with a high probability of failure. The house did not appear to be a formidable defensive position, but as we'd learned in the Western Euphrates River valley fight, appearances could be deceiving. More important, palm trees surrounded the house, and the closest bald patch of ground to land our assault helicopters was a quarter mile away. To do a direct assault, because the trees were so tall, the assault force would have had to fast-rope ninety or a hundred feet down, a towering, dangerous distanceâand one that would require the helos to float, in daylight, over the house. Doing a fast-rope would be asking to get a helicopter shot down. Most troubling, anyone inside the house could easily slip out the back, disappearing into the thick vegetation and groves. We likely wouldn't even see it happening.

Mike Flynn, Kurt Fuller, and I came out from our office into the TF 16 JOC. We took our spots on the bench at the back of the JOC room. As I had on hundreds of nights in the past two and a half years, I sat quietly and watched.

The JOC in front of us was in pained, tense anticipation. In order to secure the site and arrest anyone who escaped the blast, we wanted Tom D.'s operators to land just after the explosion. So Steve was waiting on them to be airborne and nearby before having the F-16 engage. Unbeknownst to many of us in Balad, as the troop down in Baghdad was first kitted up and loaded into the two helos taking off from in front of their villa, one of the engines wouldn't start. Tom D. and his team were stunned. This was unheard of for 160th helicopters. They sent for another helicopter, but it would be thirty tense minutes before it arrived from Balad.

As they watched the house on the screens, many in the JOC played over in their minds the worst-case scenario: They imagined seeing Abd al-Rahman and the Man in Black, spooked by the sounds in the busy sky overhead, dart from the house, disappearing into the foliage. They scoured the edges of the house, looking for movement under the carport or around the house's stucco walls. For now, it was quiet. The only movements on the screen were made by the tall palm trees, their top fronds rustling slightly, casting dark shadows across the house.

As we imagined what was happening inside the boxy, two-story house, we knew that if Zarqawi was there, he was not alone. His familyâincluding perhaps both of his wives and their childrenâoften stayed with him and would be killed in the strike.

Steve decided they couldn't wait for the Baghdad troop to be nearby. He called down to Tom D. at Baghdad. Through the receiver pressed to Tom D.'s ear, J.C. could hear Steve's go-ahead.

“Blow that motherfucker up.”

Tom D. set it in motion. “Get the first helo airborne; the other one will catch up,” he ordered. He turned to his joint tactical air controller (JTAC). “Go ahead and execute. Drop the bomb.” The JTAC relayed the order to two already airborne F-16s on a normal combat patrol flown to provide near-immediate response to emerging requirements, like bombing a target. But the answer came back that only one of the two F-16s was available. The second was on the tanker, refueling midflight, and would be delayed fifteen minutes.

It was now after 6:00

P.M.

, and Tom D. shook his head. Weeks of patient, persistent focus had gotten them here, and the final operation now seemed to be running off the rails. “We don't have fifteen minutes.” He told them to send the one that was free. The lone F-16 canted and roared through the clouds toward Baqubah.

“You are cleared to engage,” the JTAC relayed, and the JOC waited. The jets were in a three-minute hold.

A minute passed. Two minutes out.

One minute.

The jet was within miles, and the residents of Hibhib would soon hear its engines crackle through the sky overhead.

At 6:11

P.M.

, it came in on a dive, rushed over the house, and peeled up. Tom D. and the JOC watched the screen. There was no explosion. The house was still there. The F-16 had screamed low over the house's roof but left it unscathed. They called the F-16. The JTAC's earlier bomb command

had been improperly worded, they were told, so the F-16 hadn't released its munitions. Tom D. couldn't believe it. They looked to the screen, waiting to see Abd al-Rahman and the Man in Black flee into the palms.