Observatory Mansions (35 page)

Read Observatory Mansions Online

Authors: Edward Carey

When I woke, I woke because of the pain in my legs. I tried to move the rubble; I tried to roll over, but was unable to. I felt my hands throbbing, insulted, I pressed them to my mouth, kissed them. That beautiful white was ruined for ever, one of my fingers had burst out of the cotton.

I took some deep breaths and tried only to concentrate on my feet and ankles and legs, tried to remember how they were connected to me, what they felt like, how they moved.

And the moment I pictured them, I felt their pain drilling through my body. I tried to roll a little, to feel my legs moving. But the more I shifted, the more it hurt. But I wriggled on with tiny, controlled movements, and slowly I began to creep forwards, eventually, advancing inch by inch, the rubble was left behind and I sat as best I could, crouched beneath the wooden beam, hugging my wounded knees.

It would be good to light a match, I thought. It would be good to see something, no matter how bleak it was, something to take away this thick blackness, if only for a moment. I was scared of the dark, like a child. How, I wondered, did Anna feel, trapped in perpetual night. But though there were still matches in my pocket I would be unable to strike one without the use of my hands. But I tried, I shifted the box out of my trouser pocket using an elbow, and even clamped it still on the floor between my feet, but I could not open it. Then I tried holding the matchbox between my wrists and sliding it open with my tongue. But I had hold of the box the wrong way round, and as I stuck my tongue out and pushed the cardboard drawer away from me, all the matchsticks fell to the floor. Howling in frustration, I ground the matchsticks up under my shoes, cursing them. I was alone in the dark. I had lost my one chance of light, tipped it out on the floor of the tunnel.

Then I began to frighten myself, muttering, if you don’t get out you will die. If I stayed here, I thought, I would become one with the famous fat and thin Cavalier. My ghost might wander up and down and spook anyone who came to look for me; and those intruders would never return to the light again, even if they screamed out at eighty decibels, for no one would come searching in the tunnel for them because that is where the phantom of the white gloves lives with the fat and thin Cavalier, and no one wants to disturb those two. But I could not move the rubble in front of me, that was impossible, the Law of White Gloves forbade it:

Rule 7. Dead gloves cannot function. The hands underneath them will never be able to pick up, touch or move at all. They are dead.

I would scream for help. How convenient it would be for me if people came to save me. They would do all the work of shifting the rubble, while I just sat here kissing my fingers, ordering the people to hurry up. Yes, that’s what would happen. I needed only open my mouth and with one brave effort, call out. What remained of the tunnel walls would surely echo and duplicate the sound until someone heard it, then everyone would immediately start moving rubble and set about the business of rescuing me. I felt considerably better. But when I opened my mouth to scream, I could not make any noise. My throat was too dry, all I was able to hear was a thin whispering sound, which faded as soon as it was uttered.

I was like a Pharaoh buried amongst his life’s objects. But I was unable yet to let go of life. I began to aim my elbows at the rubble in front of me, scraping away in ugly, desperate gestures, trying to dislodge it. But it did not move. I thumped the rubble with my wrists. But it did not move. I kicked at the rubble. And it did not move.

Perhaps if I used my hands … but that was not permissible. Rule seven was firm about that. I would just sit here then, cramped against the jagged tunnel wall, and try to sleep the end out, try to keep quiet, try to achieve a little of that inner stillness which I had so enjoyed and loved when extinction wasn’t threatened. But, in my state of fear, I was unable to achieve inner stillness, so I attempted a prolonged session of outer stillness to calm me down. But I was incapable even of that. I fidgeted, my bleeding legs kept shaking, my hands throbbed, my brain pictured the words of the seventh rule of the Law of White Gloves and began to reduce the print size until it couldn’t be read any more, until it was out of sight.

No! I could not break the law! If I broke the law what would that lead to? The end, surely. I might become one of those other people, I might take up talking, I might even stop collecting and leave that most welcome of plinths in the centre of the city empty, I might take a movement job, and in that movement job my superior would be bound to say: Take off those gloves, Francis, and sit down, there’s a good man. And I might even become a good man and take off those gloves and what then? No, I was a glove wearer, it was understood. Glove people are a magical people, wearing gloves, monitoring everything you touched, was like floating above the world, watching everybody in it, watching all the suffering, always observing it, but never touching it. It was best not to think about breaking the Law of White Gloves, it was better just to die quietly down here in the miserable darkness.

But it was very hard not to think, there was really very little else to do. I tried to remember the names of the stars, but I needed my father’s help for that. And one thought, no matter how hard I tried to extinguish it, kept repeating itself within me, and the power of that thought was so great that it opened my mouth and made me whisper:

Rule 11. It has recently been decided that in one certain extraordinary circumstance dead hands may continue to function. When a gloved individual is suffocating and bleeding down in a dark tunnel and surrounded north and south by rubble, it has been agreed, by popular demand, that hands with dirty or ripped white cotton and even hands lacking white cotton altogether may move and be put to work.

My fingers began to shift rubble. Piece by piece, cutting that most vulnerable part of me open, progress was rewarded with more rubble and more cuts. My poor hands were being ruined for ever. They stung, they ached, but on they worked. And slowly I began to build the rubble up behind me and to

move, shifting loads, slowly, slowly along the tunnel, until after three or four breaks and curses that the rubble would never thin out, I was able to push backwards an obstructing beam and climb, scraping against the tunnel ceiling, forwards on top of the rubble. And then, finally, dusty and bloody, I felt myself descending and I was able to crawl along the floor itself.

A while later I felt the tunnel steps and slid open the tomb lid, the light burned my eyes. The first thing I saw were my betrayed hands, ugly and ashamed. My nails bled, tiny strips of jagged skin hung from ungloved fingers, the gloved fingers all had red tips. Sitting with my legs dangling, half in the church, half in the tunnel, panting and crying, I looked back into the dark. In the distance, just touched by the light, I could see a sad still life. Untidy, uncared for, lay a few, too few, objects from my exhibition, smashed and broken.

I could just see the rounded top of my last exhibit, lot 996, that most precious of all the objects. The object for which the exhibition was made. The ever-moving exhibit, destined always to be placed in the furthest spot, always to appear the most recent possession. I slipped back down, into the semidarkness.

In the tunnel the lives and loves of so many people were represented. Father was there and Twenty and Claire Higg and poor Peter Bugg and Emma, too, and even Anna Tap. But most of all, there was a person of such importance stored down there that his love was proclaimed by me as being above all those other thousands of people exhibited: lot 996, a skeleton.

I picked up this exhibit, held in its three transparent bags. I felt its polythene skin. For a moment in the half-light I thought he was alive. I thought I saw flesh grow on his skull, his eyes push out into his sockets and a large ever-smiling mouth. I thought I saw his breath caught in the polythene bag, but then the life faded again, only the head continued to

smile, a skull’s smile. The rounded top of his skull was well polished, it glistened, I had looked after it so, such a wonderful roundness. I kissed it. I studied the bag that held the precious object’s hands. I brought the bags up into the church, and laid them out on the church’s cold stone floor. I spilled out one bag, positioned the bones, there were carpals and metacarpals and phalanges too; delicate family. What tiny hands, they were. They had touched, they had collected, they had been put together palm against palm to pray, they held things, other hands among them. Brother hands to my hands. Brother skull to my skull. Brother Francis to his younger brother Thomas. My elder brother. Brother object above all other objects, the object for whom I would come to be loved always but never liked.

I slid away the cover – which only a few months ago had been removed for Father – so that only half of it was open and then I began to tip the contents of my brother on top of Father’s coffin. Up-turning the polythene bags, I began to spill my brother’s bones, back from where I had taken them. One, at least one object would be returned, I could do that much. I could at least give Father some company. I could remind him that he once had two sons, no matter how hard, for the portraits’ sake, he tried to believe that I was his eldest son. Home the bones went, each splinter, each chipped fragment of the little brother who was my senior. Back to his stone bed, stick by stick. Finally the skull, but first one final polish.

Francis, Francis?

Someone was calling.

Francis? Francis?

I’m here, Anna.

You missed it. How could you miss it? It’s fallen down, Francis. Your mother said like a once mighty elephant, its

knees buckling before it fell, groaning. They said it was a magnificent thing to have seen. You should have stayed. I called out for you. There were some huge explosions. You should’ve heard them.

I did.

The people cheered when it fell. They took photographs and cheered. There’re still lots of them there, they’ve gone among the rubble, they’re playing over what’s left of our home. It took me so long to get away. The chalk artist brought me here.

The Porter’s dead.

No one’s seen him.

He’s quite dead. The exhibition’s gone.

Yes, I suppose it must have. I’m sorry, Francis.

He was squashed, and they squashed the exhibition too.

Where are we going to sleep tonight?

All that work, all gone.

They’ll probably find us somewhere. Surely they will.

Anna, five steps away, seemed to want to come closer. She felt her way forward, made brave by the events of the afternoon. She put out her hands, searching for me through the air, striking her hands upon the chapel bars until she found the open entrance gate and then, stepping forward, her fingers rested on the object that I was holding. Her hands moved about, they felt the skull, the teeth, her fingers slipped through the eyeholes.

Francis!

It’s all right.

What is it?

It’s from the exhibition. I’m putting it back.

What is it?

Neither of us spoke. Then, after Anna’s breath had calmed, she whispered:

It’s a skull.

I’m putting it back.

You stole it.

But I’m putting it back.

You stole a skull.

He’s going back. I’m putting him back now.

Whose was it, Francis?

It’s the object Father was so upset about. They wanted him forgotten. But I remembered him. It’s my brother.

Put him back.

Back in his box.

In went the skull. I closed the lid. Lights out. I locked up the chapel. Anna was sitting on one of the front pews, if she had eyes she would have been looking at Saint Lucy. I sat beside her.

Anna, I’ve run out of gloves.

When she began to take off my ripped gloves, I did not stop her. Nor did I complain or pull away when she placed my hands to her face. Skin on skin. Skin on skin.

VIII

CITY HEIGHTS

Porter

.

The Porter, whose real name we never knew, died in the demolition of Observatory Mansions which he had helped to bring about. Among the rubble of our former home it was said that certain scavenging children found a metal trunk, identical in description to the one that was seen in the basement flat where the Porter lived, in which it was supposed all that remained of his private life was kept, all proof of his existence before he began his work in Observatory Mansions. The trunk was badly dented in the explosion and its aftermath, one of its padlocks had been ripped off – but one still remained. The children, it has been related to me, smashed open the surviving padlock and when they lifted the lid off the trunk to look inside they found nothing. The trunk was empty. This is conjecture. A rumour. It may or may not be believed.

Claire Higg

.

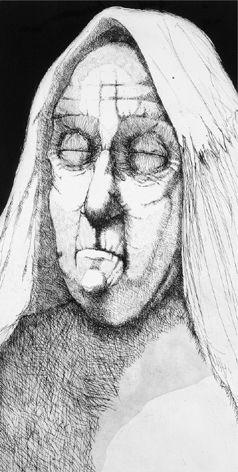

Claire Higg is dead now too. She died a little before the Porter, on the same day. During the build up to the destruction of our former home, television cameras were filming the crowd, which was large, which stood and shrieked, waiting for action. One of these television cameras was pointed in the direction of Miss Higg. The television crew had positioned monitors which displayed the various pictures being filmed by the surrounding cameras. These monitors were very near

to Miss Higg, and Miss Higg was happily watching them, feeling by their presence quite relaxed in the outdoors. Miss Higg, watching one particular monitor, suddenly saw on its screen a figure of a woman, watching a television monitor, who she knew she had once known, but couldn’t quite place. She looked at that old woman on the television monitor, that old woman had greasy hair, was bony and pale and certainly dirty. Who could it be? Concentrating intensely, she scratched her forehead. As Claire Higg scratched her forehead she noticed that the old woman on the television monitor scratched her forehead too. That disgusting old woman, who looked like she’d been kept in a shoebox for decades, even seemed to be wearing the same nightdress as her, she noticed as she looked at herself and then back at the monitor. She noticed too that the old woman had, coincidentally, exactly the same dirt patches on that identical nightdress. Then Claire Higg, former resident of flat sixteen, once loved by Mr Alec Magnitt (deceased), once perhaps loved by the Porter (soon to be deceased), realized in fact that she was that unpleasant-looking old woman. In the instant that Claire Higg saw who she was, in the instant that she saw what she had become, she immediately leapt into one of those moments of high consciousness and, filled with mounting horror, disgust and breathlessness, decided to have a heart attack on the spot. She died, of course. But she may have been comforted to know that the last moments of her life made very watchable television. This is not conjecture. This is to be believed.