One and Only (23 page)

Authors: Gerald Nicosia

Too often she took responsibility for the misdeeds of the men in her life. Partly this self-abnegation and deference toward men seems to have come from her childhood, from the guilt she felt for leaving her real dad in Los Angeles, at about 12 years old, to go live with

her mom and new stepfather in Denver. But part of giving men more than they deserved also came, according to Hinkle, from her strong sex drive, her great need to have forceful male lovers in her life, and so she would put up with a lot to keep them. She told Al that no lover ever satisfied her as well as Neal had. But she put up with a lot from her second husband, Ray Murphy, too. She'd vacillated about marrying himâespecially when it seemed she might have a chance of connecting permanently with Jack Kerouacâbut in the end she felt obligated to marry him because she'd taken his ring and promised him she would. She'd already glimpsed his heavy drinking and violent jealousy, but went ahead with the marriage anyway, blaming herself for Murphy's instability and roughness with her because she had remained too connected to Neal.

her mom and new stepfather in Denver. But part of giving men more than they deserved also came, according to Hinkle, from her strong sex drive, her great need to have forceful male lovers in her life, and so she would put up with a lot to keep them. She told Al that no lover ever satisfied her as well as Neal had. But she put up with a lot from her second husband, Ray Murphy, too. She'd vacillated about marrying himâespecially when it seemed she might have a chance of connecting permanently with Jack Kerouacâbut in the end she felt obligated to marry him because she'd taken his ring and promised him she would. She'd already glimpsed his heavy drinking and violent jealousy, but went ahead with the marriage anyway, blaming herself for Murphy's instability and roughness with her because she had remained too connected to Neal.

Though Murphy sired her only child, Anne Marie (unless we choose to believe Neal's version that

he

was the girl's father), the marriage was otherwise a disaster. Time and again, his jealousy exploded out of control, and he beat Lu Anne mercilessly for offenses which were mostly in his own imagination. Al recalls her showing up at the house on 18th Street and Valencia in San Francisco where he lived with his wife, Helen, only a few months after she'd married Murphy, with her face all puffy and black and blue. She begged him to allow her to spend the night, but refused to point the finger at Murphy for the pummeling she'd received, afraid that Al might go find Murphy and give him a taste of his own medicine.

he

was the girl's father), the marriage was otherwise a disaster. Time and again, his jealousy exploded out of control, and he beat Lu Anne mercilessly for offenses which were mostly in his own imagination. Al recalls her showing up at the house on 18th Street and Valencia in San Francisco where he lived with his wife, Helen, only a few months after she'd married Murphy, with her face all puffy and black and blue. She begged him to allow her to spend the night, but refused to point the finger at Murphy for the pummeling she'd received, afraid that Al might go find Murphy and give him a taste of his own medicine.

And Al would not have hesitated to avenge her. He admits that he had long before started to fall in love with her himself. “Her personality stood out as much as her physical beauty,” Al recalled, 60 years after she'd crawled into bed with him and his wife, and a year after Lu Anne's death. “She was always so outgoingâso loving, kind, and considerate.” His eyes looked a little misty as he recalled how she went back to Murphy against his advice.

And then Murphy came banging on his door the following night. As soon as Al let him in, Murphy lit into Al, accusing him of being a “go-between for Neal and Lu Anne,” and threatening to hurt Al if he continued doing this. In truth, Lu Anne was certainly still involved with Neal, but Hinkle had had nothing to do with helping that along. He didn't even know where Lu Anne lived, and Neal had had no trouble finding her on his own. Hinkle told him, “I don't agree with you beating the shit out of your wife,” and then offered to go outside with him and settle their differences right then and there. Murphy, he says, looked like a “tough guy,” but Al was bigger than Murphy and, since he worked on the railroad, had a few muscles of his own. Murphy, he says, turned in silence and left. Hinkle concluded that “he was a bully who preferred beating up women to fighting with other men.”

As the years went by, Hinkle continued to see Lu Anne from time to time. She showed him her baby, Annie Ree (born December 18, 1950), when the girl was about three months old. He recalls that Neal continued to see her, off and on, through the early 1950sâand he maintains that their sexual relationship actually continued sporadically till the end of Neal's life.

But Lu Anne had a number of other boyfriends during this period too. Hinkle remembers one night in particular, in about 1957, when Lu Anne again showed up at his house in the middle of the night, this time with her seven-year-old daughter in tow. She told him she had to meet a guy in Los Angeles, and could she leave Annie Ree with him and his wife for a day or two? Al agreed to help her out, but he grew increasingly concerned as the days, then weeks, passed with no word from Lu Anne. The Hinkles placed Annie Ree in school with their own daughter, Dawn, but Al was virtually in a panic, since he did not know how to contact Lu Anne's two half brothers or anyone else in her family. Finally, about three weeks later, Lu Anne returned

to pick up her daughter. She was black and blue again. “The guy turned violent” was the only explanation she ever gave Hinkle about that episode.

to pick up her daughter. She was black and blue again. “The guy turned violent” was the only explanation she ever gave Hinkle about that episode.

Â

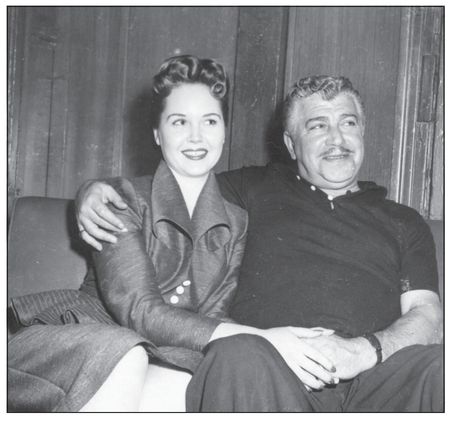

Lu Anne in her Lilli Ann fitted suit, with her third husband, Sam Catechi, Little Bohemia club, San Francisco, 1953. (Photo courtesy of Anne Marie Santos.)

Over the years, Al said, he often visited with Lu Anne on his day off; or sometimes they'd have lunch, and she would drive him back to the railroad afterward. They often reminisced about Neal, Jack, and the wild times they'd had together. For several years, she worked as a cocktail waitress at San Francisco Airport, making great tips and meeting lots of important people.

Then she surprised Al one day, in about 1953, when she told him about a Greek man named Sam Catechi, a San Francisco nightclub owner whom she'd met while cocktail-waitressing in North Beach. Catechi had quickly proposed marriage, and she'd just as quickly accepted. He was several decades older than she, a dapper guy who looked something like an overweight Clark Gable. In Al's view, he

appeared incongruous next to the gorgeous, youthful-looking Lu Anne, who was still getting carded at bars even in her late twenties. Soon after their marriage, Catechi bought her a home in Daly City. Al's take on the marriage was that Lu Anne had sought security for herself and her young daughter, which Catechi gave them. Catechi acted as a father toward Annie Ree, who took his last name, and Lu Anne kept the house even after they divorced two years later. Their parting was amiable, and Lu Anne appeared to feel gratitude toward him for more than just his financial support. She told Hinkle she'd learned a sophistication from Catechi that she'd never had before.

appeared incongruous next to the gorgeous, youthful-looking Lu Anne, who was still getting carded at bars even in her late twenties. Soon after their marriage, Catechi bought her a home in Daly City. Al's take on the marriage was that Lu Anne had sought security for herself and her young daughter, which Catechi gave them. Catechi acted as a father toward Annie Ree, who took his last name, and Lu Anne kept the house even after they divorced two years later. Their parting was amiable, and Lu Anne appeared to feel gratitude toward him for more than just his financial support. She told Hinkle she'd learned a sophistication from Catechi that she'd never had before.

Lu Anne's fourth husband, Bob Skonecki, came along in 1960, and she married him in 1963. He was another merchant seaman, the sort of big, handsome, muscular guy who was much more her type. But like Murphy, he was away at sea for long periods; and there were new, troublesome factors in her lifeâincluding serious failings of her healthâthat kept their marriage from being just a happy ride into the sunset together.

Â

Around 1953, perhaps through her connection to Sam Catechi and his Little Bohemia club, Lu Anne met another San Francisco club owner named Joe DeSanti. A powerful figure, with five clubs in the Barbary Coast and North Beach, DeSanti was romantically drawn to Lu Anne, but their affair didn't last long. For whatever reason, he wasn't her ideal lover; but eventually the relationship grew into a very close friendshipâshe often described them as like a brother and sister, looking out for each other and taking care of each other whenever necessary. At that time, Lu Anne was already growing seriously debilitated from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which she'd suffered from since childhood. With Lu Anne's health growing ever more problematic, she clearly needed someone she could rely on during bouts of illness or in other troubled times.

DeSanti became a kind of de facto godfather to Annie Ree as well. He even bought a house only a few blocks from Lu Anne's in Daly City. When Joe went to jail for two or three years on a federal tax evasion charge, he asked Lu Anne to manage one of his North Beach nightclubs for him.

DeSanti became a kind of de facto godfather to Annie Ree as well. He even bought a house only a few blocks from Lu Anne's in Daly City. When Joe went to jail for two or three years on a federal tax evasion charge, he asked Lu Anne to manage one of his North Beach nightclubs for him.

DeSanti's club was on Broadway, right in the middle of the North Beach strip, and those years when Lu Anne ran it, 1959 to 1961, opened up a new world to her. The group of San Francisco club owners and entertainers were a close-knit community, and in this small world she met people like future superpromoter Bill Graham, who often frequented Basin Street West, where everyone from Lenny Bruce to Smokey Robinson and the Miracles performed; the political glad-hander George Moscone, who would become one of the city's most famous, and later tragic, mayors; and local songster Johnny Mathis, the golden-voiced alumnus (and former star athlete) of San Francisco's George Washington High School, whom Joe turned down after an audition at his club, thinking the kid didn't show much promise, but who got work soon after at the Jazz Workshop next door. Lu Anne liked the experience so much that when Joe got out of jail, she went onâpossibly with DeSanti's or Catechi's helpâto buy her own club on Broadway, the Pink Elephant, which she personally ran from 1961 to 1963. Her daughter remembers Lu Anne's years managing that nightclub as some of the happiest of her lifeâmingling with all sorts of celebrities and powerful people, as well as getting to assert her independence and show off her management and people skills, which were considerable. But Hinkle saw a darker side to it.

To truly understand this part of the story, one has to get a fuller picture of just how ill she had become. As with many people who have chronic illnesses, which erupt and then subside, it was not always easy to see how sick Lu Anne was. When not having an acute

attack, she could look well, her beauty still shimmering, her mood still upbeatâthe very picture of health. But, in fact, she had come close to dying at least three times already. In 1957, in Tampa, an attack of her IBS had caused her so much pain that she'd been hospitalized. Annie recalls that her survival was touch and go for a few days, and that when she was finally released, she was still extremely weak and fearful that she would not recover. That was when she drafted a desperate letter to Neal, printed later in this book, that she may or may not have ever mailed.

attack, she could look well, her beauty still shimmering, her mood still upbeatâthe very picture of health. But, in fact, she had come close to dying at least three times already. In 1957, in Tampa, an attack of her IBS had caused her so much pain that she'd been hospitalized. Annie recalls that her survival was touch and go for a few days, and that when she was finally released, she was still extremely weak and fearful that she would not recover. That was when she drafted a desperate letter to Neal, printed later in this book, that she may or may not have ever mailed.

Then in 1962, in San Francisco, she had a hysterectomy, which led to the discovery of 20 stones in her gallbladder that were removed a week later. The two back-to-back surgeries led to severe blood clotting. They had to pump three cups of clotted blood out of her femoral artery; her artery was clogged from her leg all the way to her lung. She remained in the hospital for three months, during which time she almost died twice; and at one point, Joe and Annie were summoned to the hospital because she was being given last rites. Lu Anne was put on Coumadin, a powerful blood thinner, which kept her alive but resulted in frequent bleeding under her skin, which would sometimes leave whole patches of her body black for weeks on end.

Her IBS grew worse too, and for the rest of her life she suffered enormous amounts of pain. She began using Miltowns as well as powerful prescription painkillers. As Annie points out, during the sixties a wide variety of opiate drugs became easily available, and Lu Anne did not shy from using anything that helped her. But according to Al, her moving up to morphine and heroin had much more to do with the connections she retained to San Francisco's club scene through her frequent part-time jobs as bartender and waitress. At some point in North Beach, she met a guy known as Peepers,

33

who

was always trying to find people to help him score hard drugs. He would often start by offering friends a taste of whatever he was using, as a way to get them interested in acquiring more. According to Al, Peepers got Lu Anne hooked on heroin; and for several years in the mid-1970s, her life went straight downhill.

33

who

was always trying to find people to help him score hard drugs. He would often start by offering friends a taste of whatever he was using, as a way to get them interested in acquiring more. According to Al, Peepers got Lu Anne hooked on heroin; and for several years in the mid-1970s, her life went straight downhill.

After Joe got out of jail, he opened an after-hours music-and-dancing joint in the Tenderloin called the 181 Club, at which famous musicians like Nat King Cole sometimes dropped by after their regular gigs. The club was successful, but Joe was tied up for long hours working there. Annie Ree got pregnant, moved out, and began raising her own baby when she was still quite young. With Lu Anne's husband away most of the time, perhaps it was loneliness that got to her, but she began using morphine and heroin more and more heavily.

According to Hinkle, she used up her husband's merchant marine checks to pay for the drugs; and when she again ran out of money, she borrowed against her house, then had trouble making the new mortgage payments. Al knew she was starting to get in too deep when her phone was disconnected. He paid the bill for her, but he recalls that strange people would answer her door when he came over, some of whom didn't even seem to know Lu Anne, and he sensed that they were all high on drugs. Eventually Lu Anne lost her house. At some point, she moved in with Joe, a few blocks from where she used to live, but her desperation for money increased. Al remembers her frequently coming to see him on the railroad, pleading for small loans of 10 or 20 dollars, which he always gave, and promising that she would go into a Methadone treatment program soon. He was appalled by the degrading lifestyle she'd fallen into, and felt ashamed of his own inability to refuse her money, since he knew he was contributing to her downfall by helping finance her habit.

Al recalls that Annie Ree was really worried about her mom at

this time, and of course Al and his wife, Helen, were too. Lu Anne's husband, Bob, was highly disapproving of her drug use, in fact would not tolerate it, and so the two separated for a while. At one point, Al says, Lu Anne actually disappeared for almost six monthsâthough it turned out she had merely gone back to Denver. As sympathetic as Al was, and as pained as he felt to witness Lu Anne's humiliation, he was also puzzled and a bit dismayed that a woman in her forties would allow herself to become hooked on hard drugs. He could see people experimenting in their youth, he says, but he felt that somebody in middle age should know better than to embark on such a dangerous lifestyle. It also didn't accord with the Lu Anne he and his wife thought they knewâthe woman who was usually so truthful and outgoing and loving, who didn't seem to have a selfish bone in her body, who loved children and in fact often babysat Neal's kids (without Carolyn's knowledge) when they were young, the woman who would endlessly do kind things for her friends, like passing her own daughter's clothes and toys on to the Hinkles for their daughter, Dawn, who was two years younger than Annie Ree.

this time, and of course Al and his wife, Helen, were too. Lu Anne's husband, Bob, was highly disapproving of her drug use, in fact would not tolerate it, and so the two separated for a while. At one point, Al says, Lu Anne actually disappeared for almost six monthsâthough it turned out she had merely gone back to Denver. As sympathetic as Al was, and as pained as he felt to witness Lu Anne's humiliation, he was also puzzled and a bit dismayed that a woman in her forties would allow herself to become hooked on hard drugs. He could see people experimenting in their youth, he says, but he felt that somebody in middle age should know better than to embark on such a dangerous lifestyle. It also didn't accord with the Lu Anne he and his wife thought they knewâthe woman who was usually so truthful and outgoing and loving, who didn't seem to have a selfish bone in her body, who loved children and in fact often babysat Neal's kids (without Carolyn's knowledge) when they were young, the woman who would endlessly do kind things for her friends, like passing her own daughter's clothes and toys on to the Hinkles for their daughter, Dawn, who was two years younger than Annie Ree.

Other books

The Maid and the Queen by Nancy Goldstone

A Year of Marvellous Ways by Sarah Winman

The Train Was On Time by Heinrich Boll

Red Angel by Helen Harper

Pigeon Summer by Ann Turnbull

Jumping In by Cardeno C.

Ashley's Bend by Roop, Cassy

Pressure Rising (Rhinestone Cowgirls Book 2) by Carver, Rhonda Lee

Bartered Bride Romance Collection by Cathy Marie Hake

2009 - We Are All Made of Glue by Marina Lewycka, Prefers to remain anonymous