One and Only (24 page)

Authors: Gerald Nicosia

The only possible explanation Al could come up with for Lu Anne's big downhill detour late in life was that it was “a middle-age thing.” He said she would sometimes wonder aloud, “What's left for me?” But it seems there was more than that going on. All the evidence points to the fact that she had never gotten over her love for Neal Cassady, and that the tragic end of his own life was absolutely devastating for her.

Although she truly loved Bob Skonecki, Lu Anne could never break off her sexual relationship with Neal even after she took vows with her fourth husband. The connection she had with Neal seemed to override everything else she had in her life. Al recalls how happy she wasâjust bubbling over with laughter and merrimentâwhen Neal drove them over to see Jack at his little cottage in Berkeley in

1957. He also recalls how worried she was about Neal the following year, when he was in San Quentin. Deeply mortified to have landed in such a place, Neal did not want to write letters to the majority of his friends while in prison (though he did keep up a faithful correspondence with Carolyn). For the most part, he also did not want to see visitors. Lu Anne had no way of getting word of his condition, and she feared for his life. Finally, arrangements were made with the prison, and Al drove her over to Marin County to see him. She asked Al to leave them alone together during the visiting period. Afterward, he says, she was enormously relieved to have found that Neal had achieved some sort of tranquility in jail, and that he was doing his best to earn an early release. It was clear to Al that she still cared a great deal about Neal, and that Neal's state of mind profoundly affected hers, as if there were some sort of communication wire between their psyches.

1957. He also recalls how worried she was about Neal the following year, when he was in San Quentin. Deeply mortified to have landed in such a place, Neal did not want to write letters to the majority of his friends while in prison (though he did keep up a faithful correspondence with Carolyn). For the most part, he also did not want to see visitors. Lu Anne had no way of getting word of his condition, and she feared for his life. Finally, arrangements were made with the prison, and Al drove her over to Marin County to see him. She asked Al to leave them alone together during the visiting period. Afterward, he says, she was enormously relieved to have found that Neal had achieved some sort of tranquility in jail, and that he was doing his best to earn an early release. It was clear to Al that she still cared a great deal about Neal, and that Neal's state of mind profoundly affected hers, as if there were some sort of communication wire between their psyches.

Â

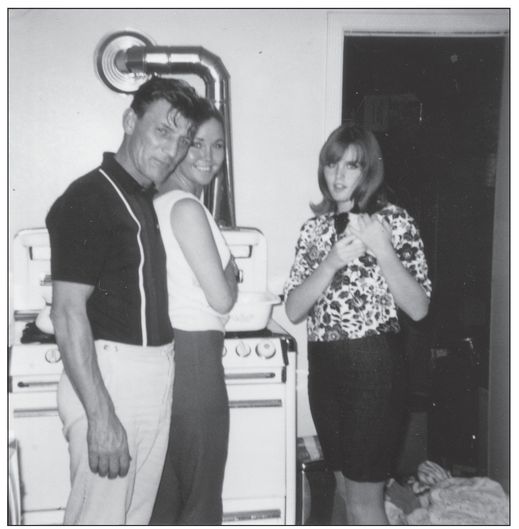

Bob Skonecki (Lu Anne's fourth husband), Lu Anne, and Annie, age 13, holding Junior, her Maltese terrier, Daly City, 1964. (Photo courtesy of Anne Marie Santos.)

Â

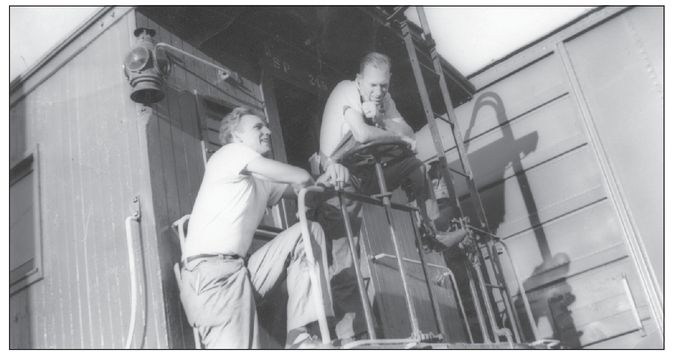

Al Hinkle with coworker, Southern Pacific Railroad, July 9, 1954. (Photo courtesy of Al Hinkle.)

Hinkle also recalls how, during the sixties, Lu Anne would meet fairly often with Neal for clandestine sex. Until 1963, of course, he was still married to Carolyn; and from late 1963 on, she was married to Skonecki. But the marital status of neither one proved an obstacle to these rendezvous, the urgency of which both Neal and Lu Anne seemed to feel keenly. Occasionally Hinkle would abet their trysts. By prearrangement, Neal would wait in San Jose on certain days when Al brought her down from San Francisco on the train. There'd be big hugs and kisses as soon as they came together, and then Neal would spirit her off in his car to a motel or somebody's empty bedroom, where they'd share a few hours of bliss in each other's arms. Other timesâAl learned from NealâLu Anne would simply drive down to San Jose in her car and call Neal to

come meet her. Her daughter would be left in the care of Joe or one of the many people who spent time living at their house. As far as Hinkle knew, nobody else in their lives, including Carolyn Cassady and Annie Ree, was aware of these secret love meetings.

come meet her. Her daughter would be left in the care of Joe or one of the many people who spent time living at their house. As far as Hinkle knew, nobody else in their lives, including Carolyn Cassady and Annie Ree, was aware of these secret love meetings.

When Neal was found dying beside the railroad tracks in San Miguel de Allende in 1968, Annie Ree, barely 17, was having her own difficulties and was not there for Lu Anne, to talk through all the things her mother must have been feeling. Nor could Lu Anne easily have talked with Skonecki about Neal's death, even had Skonecki not been absent so much of the time. Joe stayed with her during some of her worst times. Still, Lu Anne retreated into herself. Never much of a drinker, she got so drunk and disoriented one night that she ended up falling asleep in a stranger's house. Four years after Neal's death, she tried heroin, and found herself compelled to ride the self-destructive train almost to the same place where it had taken Jack and Neal.

But Lu Anne proved herself stronger than they were. Maybe it was her love for her child and grandchild that saved her, but one also feels there was a strength in Lu Anne from the very beginning that always let her land on her feet, always kept her one step ahead of the pack of troubles that dogged her for most of her life. After all, as a willowy teenager only halfway through her high school years, she survived the worst tricks and knockdowns a hardened ex-con like Cassady (for in many respects that's what he was) could toss at her. She also survived a host of physically abusive, sometimes brutal men. Some might think there was a streak of masochism in her that brought her back to men like that time and againâbut that would have been a matter for a trained therapist to dissect, and she's gone now and beyond the reach of analysis. I would merely suggest here that there is an alternate explanationâthat the lady honestly sought love as her highest goal, that she needed love more than anything,

craved it, and was willing to risk anything, even her own well-being, to find it.

craved it, and was willing to risk anything, even her own well-being, to find it.

In any case, according to Hinkle, at some point around the early 1980s, Lu Anne took herself back to Denver again, determined to get off heroin. Hidden away from everyone except her longtime friend Jimmy Holmes, who was himself dying at that time, she put herself through a rehab program and got clean. And as far as anyone knows, she did not use hard drugs ever again for the rest of her life.

She and Skonecki reconciled, took their savings (for she'd managed to keep a little money from the sale of her house), and bought a trailer up in Sonoma County, an hour or so north of San Francisco. There they seemed like the ideal, loving, and contented retired couple. Lu Anne's kindness and thoughtfulness returned in full force. When Al's wife, Helen, died of cancer in 1994, she called him and comforted him greatly. Al returned the favor by visiting Lu Anne several times after Skonecki died in 1995. Bereft herself, she comforted Al again when his second wife, Maxine, whom he married in 1996, fell victim to Alzheimer's disease only a few years later. She remained in her trailer in Sonoma, where Al would find her ensconced amid hundreds of dolls, with a loyal dog for companionship. Her old girlfriend Lois was now dead, and she had also lost her half brother Lloyd, whom she'd been close to.

But she soon found a new companion. She met Joe Sanchez, a Mexican American man who had dated Lloyd's widow for a while. Originally from Los Angeles but now suffering through the Denver winter, he told her he was broke and had no place to stay, so she invited him to move into her spare bedroom in Sonoma. He lived there happily for several yearsânot so different from the stray people Annie Ree remembers ending up at their house in Daly City several decades earlier. By this time, Lu Anne had her own social security benefits as well as Skonecki's merchant marine pension, and

her financial worries were long gone. Just as she always had, she felt it was her duty to help people who were less fortunate than she.

her financial worries were long gone. Just as she always had, she felt it was her duty to help people who were less fortunate than she.

If she were no longer the overtly joyous, impulsive, hell-for-leather young pinup girl she had once been, she was, according to Al, “not unhappy.” She had gained a little weight and appeared slightly “plump,” but most people found her still beautiful. Whenever they got together, she would ask Al about Ginsberg and other people they knew from the old days who were still alive, like Hal Chase. But when he left a message on her answering machine about Ginsberg reading at Stanford and offered to drive her there and back, she never responded.

Â

Annie and Lu Anne, Lu Anne's last apartment, Clayton Street, San Francisco, 2008. One of the last known photos of Lu Anne. (Photo courtesy of Anne Marie Santos.)

Until she became very sick with cancer during the last year of her life, Lu Anne would call Al about every three or four months to see how he was doing, but she almost never took calls from him or anyone else. She became famous for using her answering machine to screen all her calls, as if she were now relishing her solitude and reluctant to give it up except when she chose to. Often in her calls to check up on him, she'd promise Al that she would “come down soon to see ya,” but she never did.

When they did talk, in person or on the phone, he noticed that she avoided talking about Neal, as if the subject came with a pain she didn't want to revive. Likewise, she avoided any specific references to the Beat world, and would brush Al off quickly whenever he suggested she should visit or speak at the new Beat Museum in San Francisco. If he'd ask her questions about their time in New York, she'd always answer him, and even talk readily about it, but she would never bring up the subject herself.

Once, he asked her who the musicians were that they had heard up in Harlem with Jack and Neal. He was astonished when she named every person in that bandâshe recalled the trumpeter, drummer, clarinetist, every instrument and every player there.

“Her memory was still perfect,” he said.

Letter to Neal

A

nne Santos found this handwritten, unsent letter among her mother's papers in her San Francisco apartment after her death. It is clearly written to Neal Cassady. Anne believes it was written in Tampa, Florida, in 1957, just after her mom got out of the hospital following a serious illness, during which Lu Anne may have had to confront her possible death. The handwriting, in light-blue pen, has faded over the years, and her spelling and punctuation are nonstandard, so deciphering the letter was no easy task. In one place, where I was not certain of the reading, I marked the doubtful word with a question mark.âG.N.

nne Santos found this handwritten, unsent letter among her mother's papers in her San Francisco apartment after her death. It is clearly written to Neal Cassady. Anne believes it was written in Tampa, Florida, in 1957, just after her mom got out of the hospital following a serious illness, during which Lu Anne may have had to confront her possible death. The handwriting, in light-blue pen, has faded over the years, and her spelling and punctuation are nonstandard, so deciphering the letter was no easy task. In one place, where I was not certain of the reading, I marked the doubtful word with a question mark.âG.N.

Â

Lu Anne's letter to Neal from Tampa, Florida, 1957, page 1. (Ccourtesy of Anne Marie Santos.)

Other books

In the Blood by Sara Hantz

Legends of the Ghost Pirates by M.D. Lee

Target: Rabaul by Bruce Gamble

The Girl Who Could Silence the Wind by Meg Medina

The Summer Bones by Kate Watterson

Stuck On You by Christine Wenger

Burning Lust (An MMF Bisexual Threesome) by Roxie Noir

Starhawk by Jack McDevitt

Desire in the Arctic by Hoff, Stacy

Outlander (Borealis) by Bay, Ellie