One and Only (27 page)

Authors: Gerald Nicosia

The love of fine clothing was another thing she shared with me. She'd always loved fine clothing. When she was pregnant with me, one of her jobs was modeling at one of the bigger department stores

downtownâit might have been Emporium Capwell. In those days, the stores had ladies who would walk the runways to show their clothing lines. Lu Anne did this till she was eight months pregnant, because she was so thinâincredibly, nobody noticed that she was carrying me! She was five foot seven and a half inches tall, and with heels she was easily five foot nine, and she weighed only 112 pounds. She could wear clothes beautifully; she had that long, lean, elegant look. She had a closet full of Lilli Ann suitsâshe knew all the names of the lines. She'd take me to a famous women's tailor in San FranciscoâI think her name was Olga Galganoâand have outfits tailor-made for both of us. Lu Anne had fur stoles, a hundred pairs of shoesâmost of them high heelsâand purses that matched every outfit. She had charge accounts at all the good stores. One of her favorites was I. Magnin, but we'd go to all of them, including City of Paris. She kept all her clothes for decades, took immaculate care of themâuntil a big fire in our house in 1960 destroyed just about everything we had.

downtownâit might have been Emporium Capwell. In those days, the stores had ladies who would walk the runways to show their clothing lines. Lu Anne did this till she was eight months pregnant, because she was so thinâincredibly, nobody noticed that she was carrying me! She was five foot seven and a half inches tall, and with heels she was easily five foot nine, and she weighed only 112 pounds. She could wear clothes beautifully; she had that long, lean, elegant look. She had a closet full of Lilli Ann suitsâshe knew all the names of the lines. She'd take me to a famous women's tailor in San FranciscoâI think her name was Olga Galganoâand have outfits tailor-made for both of us. Lu Anne had fur stoles, a hundred pairs of shoesâmost of them high heelsâand purses that matched every outfit. She had charge accounts at all the good stores. One of her favorites was I. Magnin, but we'd go to all of them, including City of Paris. She kept all her clothes for decades, took immaculate care of themâuntil a big fire in our house in 1960 destroyed just about everything we had.

There was one other benefit of having Lu Anne as a mom. She knew all the cops in San Francisco. I remember once when I was about 16, getting pulled over in a car full of kids, and the cops started to take our names. When they got to me, and I said, “Anne Catechi,” the cop lifted an eyebrow and asked, “Are you Lu Anne's daughter?” When I said yes, he let us go!

Â

Eventually, of course, the Beat world intruded into our cozy domesticityâas it was bound to do. I think my mother kept it away from our household as long as she could partly because of her not wanting any more drama in her life, and her feeling that we already had enough drama with Joe, his clubs, and all the characters who kept wandering through our homeânot to mention her frequent medical emergencies and everything else. She knew that the Beats were high

drama, and she didn't want to be drawn back into it, didn't want it to come into our everyday life. It was certainly not her best day when Neal Cassady showed up at our house.

drama, and she didn't want to be drawn back into it, didn't want it to come into our everyday life. It was certainly not her best day when Neal Cassady showed up at our house.

It was 1966, and I was already enjoying the Bay Area counterculture. Despite my mother's warnings to “stay away from Bill Graham and that crowd he hangs around with,” I'd already been to the Fillmore Auditorium many timesâto see Janis Joplin and Big Brother, Steppenwolf, the Grateful Dead, and so many other great countercultural bands. Of course, my mother was rightâpeople were doing every kind of drug that you could imagine at those concerts. I wasn't doing the drugs, but I liked the music. We lived in Daly City, but I went to all the free concerts in Golden Gate Park, and to the Haight-Ashbury to buy earrings and peasant skirts. I grew up in the era of the hippies, so I must admit that Beats, beatniks, and the Beat Generation were as far from my world as the flappers of the 1920s.

Â

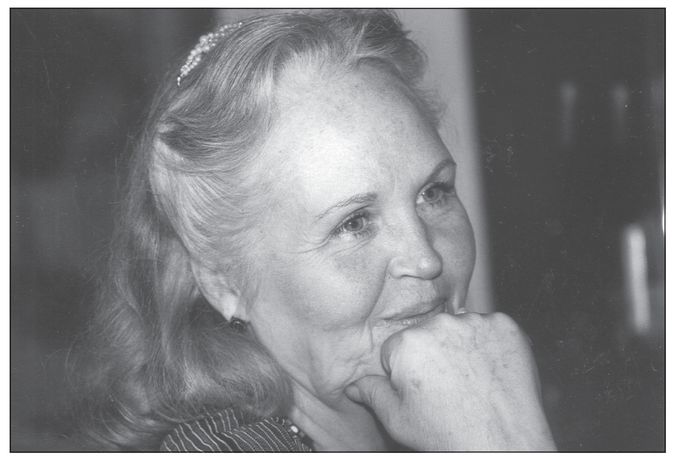

Lu Anne, Sonoma, between 2000 and 2003. (Photo courtesy of Anne Marie Santos.)

I was 16 years old when I met Neal Cassady, and I was absolutely baffled when he showed up at our house. My boyfriend Gene and I were home one afternoon when I opened the door to a man asking for my mother. Nothing special struck me about him, except he looked a little wild-eyed, like he was on speed. It was his introduction that left a lasting impression on me, and not in a positive way. He said, “I'm Neal, and I was your mother's first husband. And you are not nearly as pretty as Al Hinkle said you are.” I don't even remember what was said after that! You don't tell a 16-year-old girl she's not pretty. The husband part was just an afterthought. He let me know that he and his friends needed a place to sleep, but I wasn't about to ask them in. Of course, by the time my mother arrived home, I was pacing. The DayGlo-painted bus “Furthur” was still parked in front of our house.

“Who is this crazy person?” I demanded. After my mom dealt with Neal and his friends, she came back in and said, “Yes, I did get married when I was quite young in Denver, and then we divorced and I came to California. That's when I met your dad and married him.” Since Lu Anne's marriage to my dad had only lasted a year, I did not know my biological father eitherâso now there were two previous husbands I was in the dark about. It was clear my mom was uneasy about the visit and didn't want to tell me any more than she had to about Neal, so I didn't ask her any more questions. I was used to her keeping parts of her life off-limits to me, and I didn't want to make her uncomfortable by prying into those areas. Plus I was always much more interested in her stories from the time we called “the Jack Benny years,” when her father worked for United Artists Studios and was the bodyguard for Mr. Benny, in the 1930s.

It turned outâI later learnedâthat the bus had been filled with Pranksters and members of the Grateful Dead, who'd been hoping to come in our house to crash for a while. If I had known that, being

a big fan of the Dead, I would probably have invited them in with open arms.

a big fan of the Dead, I would probably have invited them in with open arms.

It's funny that I could grow up and be so totally unaware of such an attachment as my mom's love for Neal. I was aware, even despite the long distance, of her half brothers and other people in her lifeâpeople who'd been significant in Denver, for instance. But I have no recollection of Neal ever being around until that day when he showed up in the painted bus. My mother did not include him, or invite him, into any part of our life. She still kept that relationship totally separate. To think that there was someone my mother had been so close toâand this life she had been so much wrapped up inâand yet I was totally unaware of it, seems strange. My mother usually was open, but she kept that part, the Beat part, totally compartmentalized, so that it was not part of my world at all. I think she just put that part of her life away. If Neal would reach out, she'd be there for him, but she didn't want that to be her life, her reality, now.

Later on, I actually wondered why she didn't bring him over and say, “Oh, hey, this is Neal,” instead of keeping him so sequestered from me. It also amazed me that he actually abided by that. He seemed like the type who would selfishly drop in when he felt like it, but for most of those years he'd always go through Al Hinkle when he needed to see her, and Al would come and pick her up. When he did finally drop in with the bus and the Grateful Dead, in 1966 or 1967, it was close to the end of his life. Maybe he didn't care anymore.

It took my mother years to finally open up to me, and to start telling me her Beat stories. She always made it seem as if the Beats were not a big deal. It was not until

Heart Beat

was being filmed in 1978, and people started showing up wanting to interview her, that I began to get a little hint that Lu Anne had led some sort of life different than the one I'd known. But the only thing I heard at that point was that a friend of my mother's had been a writer and

had written a bookâthat it was about some people in New York that people were now interested in. My mother made it seem like the main interest in the movie was that these famous actors like Sissy Spacek and Nick Nolte were in it. She still didn't talk to me about the Beat Generation or beatniks. I remember that I did sense some rivalry she had with Carolyn Cassady, because when Al would drive her to the set in San Francisco, she always made sure she looked her best. Sometimes she would even borrow my clothes to look more modern, to look younger, knowing people would be comparing her to Carolyn. I knew that my mother's first husband was one of the people they were making the movie about, but that was all.

Heart Beat

was being filmed in 1978, and people started showing up wanting to interview her, that I began to get a little hint that Lu Anne had led some sort of life different than the one I'd known. But the only thing I heard at that point was that a friend of my mother's had been a writer and

had written a bookâthat it was about some people in New York that people were now interested in. My mother made it seem like the main interest in the movie was that these famous actors like Sissy Spacek and Nick Nolte were in it. She still didn't talk to me about the Beat Generation or beatniks. I remember that I did sense some rivalry she had with Carolyn Cassady, because when Al would drive her to the set in San Francisco, she always made sure she looked her best. Sometimes she would even borrow my clothes to look more modern, to look younger, knowing people would be comparing her to Carolyn. I knew that my mother's first husband was one of the people they were making the movie about, but that was all.

When my mother did finally start to tell me her Beat stories, they were mostly the famous ones that I'd already heardâabout her running off to Nebraska with Neal when she was 16, stealing her aunt's money, going to New York and meeting Jack Kerouac, and so forth. But there was one funny story I remember, about when Neal had taken her up to his cabin up in the mountains, and they were having a big drunken party with some of his friends, using pot too, and there were a lot of underage girls present. Somebody called the cops, and they all got arrested and taken to the jail in Golden, Colorado. At first, my mother refused to give the cops her name, so they locked her up with a woman who had murdered her baby. This woman was really tough; she claimed she knew gangsters from Chicago, and she told my mom they could break out of jail together. My mother played along with her. The woman asked Lu Anne if she could get a car. My mother said, “No problem.” Then the woman asked her, “Can you get any guns?” My mom answered, “Guns? Got 'em!” Of course, eventually Lu Anne had to give her name, and they released her to her family. But when she told Neal the story, he laughed, and whenever he wanted to tease her, he'd look at her and say, “Guns? Got 'em!” and they'd both crack up.

The thing was, my mother really seemed to have a lot of scorn for the people who wanted to learn about the Beats. In the early '70s, and even into the '80s, Lu Anne would kind of laugh about the way the Beat fans idolized them, how these people would think all their cross-country rides were the best of times. “We were just kids, just surviving,” my mother told me. “If we needed to go somewhere, we'd hop into a car and drive. Maybe the car didn't belong to Neal, since if he needed to get somewhere he'd grab any car he could find. If you were freezing to death and you needed a coat, you just took it, or if you needed food and you were broke, you'd get up from a restaurant without paying. We were survivingâit wasn't a joyride by any stretch of the imagination.” Lu Anne would scoff at people who would say, “Oh, you people must have had the time of your lifeâyou were so freewheeling!”

But she laughed the most at the people who wanted to recreate what they'd done. In the 1970s, some woman came to see her and told her, “I took the same trips you tookâI followed your footsteps across the country.” My mother said to me, “Who would want to recreate freezing to death and starving to death? We went for a purpose. Neal wanted to become a writer. Like everybody else does when they're eighteen or twenty, you go somewhere, you might starve for a while, but you're trying to build your life and your dream.”

When my mom finally told me these stories, she stressed to me that they had just been trying to live their lives; they weren't thinking they were creating this generation that people were going to follow. And of course there was a slow evolution in her own understanding of it as well. Jack's novel was a big deal when it came out in 1957; but then by the late 1960s, most of his books were out of print. No one was coming to see her then, no one was looking her up to ask her questions; and it wasn't till the late 1970s, when people started writing books about them and Carolyn's movie got made, that my

mother began to realize that this is bigger than just about me, just my story, it's something that a lot of people in the world want to know about. Earlier, in the '50s and '60s, she'd never dreamed that people were going to seek her out, that they would want to find out all about her life and the lives of her friends.

mother began to realize that this is bigger than just about me, just my story, it's something that a lot of people in the world want to know about. Earlier, in the '50s and '60s, she'd never dreamed that people were going to seek her out, that they would want to find out all about her life and the lives of her friends.

Â

In the last few years, my mother became interested in the fact that Francis Ford Coppola, and then Walter Salles, was going to make a movie of

On the Road

, and her story was actually going to be told in a bigger and hopefully better way than it had been in

Heart Beat.

She kept waiting for them to get started with the filming, but it didn't happen till after she died. I felt sad about that, that she didn't live to see the movie come out. But I was glad when Walter Salles asked me to come up to Montreal to talk to the actors, especially Kristen Stewart, who was going to play my mom. It gave me a chance to try to tell the story she would have told them, had she lived.

On the Road

, and her story was actually going to be told in a bigger and hopefully better way than it had been in

Heart Beat.

She kept waiting for them to get started with the filming, but it didn't happen till after she died. I felt sad about that, that she didn't live to see the movie come out. But I was glad when Walter Salles asked me to come up to Montreal to talk to the actors, especially Kristen Stewart, who was going to play my mom. It gave me a chance to try to tell the story she would have told them, had she lived.

When I went to Montreal, I was a little concerned about the fact that Kristen didn't seem the right type to play my mother. I had to keep forcing myself to remember that she was representing a fictional character in a book, that this was not actually a biography of my mother. I didn't think that Kristen could actually try to be my mother, because she's totally opposite of my mother in so many ways. Kristen is small, petite, with an almost brooding type of personality, where my mother was bubbly, smiley, full of sunshine. My mother was gentle; Kristen swears quite a bit, she's foul-mouthed and comes on tough. But once I met her, she was very curious about what it was like to grow up with my mother, what kind of experience I had as a child with a mother who had been through this whole adventure. Kristen just wanted to know about my whole experience as a child.

I found that Kristen is very, very committed to the part, that she wants to represent my mother in her own right, not as “a shadow to the boys,” as she put it. She was very protective of my mother, and very defensive about what Carolyn Cassady had written about her. Kristen felt that Carolyn was trying to make my mother look bad, that she treated my mother as if she was cheap and low-class. Carolyn had written the story as if she was the socialite, and as if my mother was just this young girl who was easy, who was brought along just as a sex object for these guys. Kristen felt that Carolyn had not portrayed my mother in a very good light, that she'd made her seem like just this young kid Neal happened to marry before he knew any better. She told me straight off that that was

not

how she wanted to play the role of Lu Anne.

not

how she wanted to play the role of Lu Anne.

Other books

The Tycoon's Misunderstood Bride by Elizabeth Lennox

The Secret Ways of Perfume by Cristina Caboni

Ten Tiny Breaths 0.5 In Her Wake by K.A. Tucker

The Sweet Girl by Annabel Lyon

The Attic Room: A psychological thriller by Linda Huber

Legacy by Ian Haywood

Bro on the Go by Stinson, Barney

Quirkology by Richard Wiseman

The Beloved One by Danelle Harmon

Venetia by Georgette Heyer