Oral Literature in Africa (11 page)

Read Oral Literature in Africa Online

Authors: Ruth Finnegan

As a result of these varied theories there was a turning away from the more systematic and empirical foundations laid earlier in the century towards a more limited approach to the subject. Different as the theories are in other respects, they all share the characteristics of playing down interest in the detailed study of

particular

oral literatures and, where such forms are not ignored altogether, emphasize the bare outline of content without reference to the more subtle literary and personal qualities. In many cases, the main stress is on the ‘traditional’ and supposed static forms, above all on prose rather than poetry. The detailed and systematic study of oral literature in its social and literary context has thus languished for much of this century.

This is not to say that there were no worthwhile studies made during this period. A number of gifted writers have produced valuable studies, often the fruit of long contacts with a particular culture and area,

27

and many short reports have appeared in various local journals. But with the exception of a handful of American scholars and of the well-founded South

African school,

28

most of these writers tended to work in isolation, their work not fully appreciated by scholars.

Another apparent exception to this general lack of concern with oral literature was the French interest associated with the

négritude

movement and the journal (and later publishing house)

Présence africaine

.

29

But this, though profoundly important in influencing general attitudes to African art, was primarily a literary and quasi-political movement rather than a stimulus to exact recording or analysis. It rests on a mystique of ‘black culture’, and a rather glamorized and general view is put forward of the moral value or literary and psychological depth of both African traditional literature and its contemporary counterparts in written form. Thus, though a few excellent accounts have been elicited under the auspices of this movement, mainly by local African scholars,

30

many of its publications are somewhat undependable as detailed contributions to the study of oral literature. Its romanticizing attitudes apart, however, this school has had the excellent effect of drawing interest back to the

literary

significance of these forms (including, this time, poetry). But it cannot be said that this interest did very much to reverse the general trend away from the recognition of African oral literature as a serious field of scholarship.

By the late 1950s and 1960s, however, the situation started to change. There was a rapidly increasing interest in African studies as a whole, expressed both in the recognition of Africa as a worthwhile field of academic study and in a marked proliferation of professional scholars concerned with different aspects of African life. Work became increasingly specialist. With the new boom in African studies, those who before were working in an isolated and limited way, or in only a local or amateur context, found their work gradually recognized. Some of the earlier work was taken up again,

31

and the interests of certain professional students of Africa widened—not least those of British anthropologists, who for long had held a near monopoly in African studies but who were now turning to

previously neglected fields. The result has been some renewal of interest in African oral literature, though—unlike most branches of African studies—it can hardly yet be said to have become consolidated as a systematic field of research.

To mention all the contributory streams in the present increasing interest in African verbal art would be tedious and nearly impossible. But certain of the main movements are worth mentioning, not least because each tends to have its own preconceptions and methods of research, and because in several cases groups are out of touch with others working on the same basic subject from a different viewpoint.

The musicologists represent a very different approach from all those mentioned previously. Though their primary interest is, of course, musical, this involves the recording and study of innumerable songs—that is, from another point of view, of poetry. It is true that the words of songs are not always recorded or published with the same meticulous care as the music itself. But in a number of cases the words do appear, and this approach has had the invaluable effect of drawing attention to the significance of poetic forms so neglected in most other approaches. The musicologists furthermore have provided a much needed corrective to earlier emphases on the traditional rather than the new and topical, by giving some idea of the great number of ephemeral and popular songs on themes of current interest. The African Music Society in particular, centred in Johannesburg, has built up a systematic and scholarly body of knowledge of African music, mainly that of southern and central Africa but with interests throughout the continent. Its main stimulus has come from Hugh Tracey, who has taken an interest in oral art as well as music for many years (e.g. Tracey 1929, 1933, 1948

b

), but its activities are now finding a wider audience not least through its issue of large numbers of records in the

Music of Africa

series.

32

Altogether it can be said that the musicologists, and above all the African Music Society, have done more both to co-ordinate scientific study and to publicize the results in the field of sung oral literature than any other group in this century.

Another significant contribution is that made by a small group of American anthropologists working closely together, and publishing much

of their work in the

Journal of American Folklore,

an academic publication which has taken an increasing interest in Africa in recent years.

33

There has always been a tradition of serious interest in oral literature among American anthropologists,

34

unlike the British, but this has recently gained further momentum and there are now a number of American scholars engaged in the serious study of African oral art.

35

Their main field of interest is the southerly part of West Africa and they seem to have less acquaintance with the work, say, of the South African school; but their general aspiration is to establish the study of oral literature over the continent as a whole. This group has to some extent been influenced by the contributions of the historical-geographical school, but takes a wider approach and, consonant with its anthropological interests, is concerned not only to record oral art (including poetry) but also to relate it to its social context rather than just analyse and classify the types and motifs of narrative. They point out the importance of considering individual inspiration and originality as well as the ‘traditional’ ‘tribal’ conventions, the role of poet and audience as well as subject matter. Though they have not always managed to pursue these topics very far in practice, the points they make about the direction of further research are so valid and, at the same time, so unusual in the study of African oral literature that this group assumes an importance in the subject out of all proportion to its size.

Some of the most original work has come from the growing numbers of Africans carrying out scholarly analyses of oral literature in their own languages. These writers have been able to draw attention to many aspects which earlier students tended to overlook either because of their theoretical preconceptions or because they were, after all, strangers to the culture they studied. Writers like Kagame on Rwanda poetry, Babalola on Yoruba hunters’ songs, or, outstanding in the field, Nketia on many branches of Akan music and literature, have been able to explore the overtones and imagery that play so significant a part in their literature and to add depth through their descriptions of the social and literary context. They have

been among the few scholars to pay serious and detailed attention to the role of the poet, singer, or narrator himself. Not all such writers, it is true, have been saved even by their close intimacy with language and culture from some of the less happy assumptions of earlier generalizing theorists. But with the general recognition in many circles of African studies as a worthwhile field of research, an increasing number of local scholars are both turning to detailed and serious analysis of their own oral literature and beginning to find some measure of encouragement for publication of their results.

36

And it is from this direction above all that we can expect the more profound and detailed analyses of particular oral forms to come.

37

Other groups or individuals need only be mentioned briefly; many of them have mainly localized or idiosyncratic interests. The strong South African school has already been mentioned and continues to take an interest in oral literature (both prose and intoned praise poetry) in Bantu Africa as a whole. In the Congo a number of scholars have for some years been working closely together, though relatively little in touch with the work of other groups. They tend to concentrate on the provision and analysis of

texts,

some on a large scale, but with perhaps rather less concern for social background and imaginative qualities; there have, however, been a few striking studies on style, particularly on the significance of tone (e.g. Van Avermaet 1955). Swahili studies too continue to expand, mainly focused, however, on traditional written forms, with less interest in oral literature. Traditional written literature in African languages generally is gaining more recognition as a field of academic research; strictly, this topic is outside the scope of this book, but is none the less relevant for its impact on attitudes to indigenous African literature as a whole.

Oral literature, like any other, has been and is subject to all the rising and falling fashions in the criticism and interpretation of literature and the human mind. Thus with African literature too we have those who interpret it in terms of, for instance, its relevance for psychological expression,

38

‘structural characteristics’ beyond the obvious face value of the literature

(sometimes of the type that could be fed into computers), its social functions,

39

or, finally and most generalized of all, its ‘mythopoeic’ and profoundly meaningful nature.

40

All these multifarious approaches, to oral as to written literature, can only be a healthy sign, even though at present there are the grave drawbacks of both lack of reliable material and lack of contact between the various schools.

All this has had its effect on the older established disciplines within African studies. The linguists, for instance, who have in any case been taking an increasingly systematic interest in Africa recently, have been widening their field to include a greater appreciation of the literary aspect of their studies.

41

The British social anthropologists, influenced by increasing contacts with colleagues in France and America and by co-operation with linguists, are also beginning to take a wider view of their subject,

42

and French scholars too have recently produced a number of detailed and imaginative studies.

43

Besides these direct studies, there is a growing awareness by other groups of the significance of oral literature as an ancillary discipline: historians discuss its reliability as a historical source, creative writers turn to it for inspiration, governments recognize its relevance for propaganda or as a source in education.

44

Much of this does not, perhaps, amount to systematic study of the literature as such—but it at least reflects an increasing recognition of its existence.

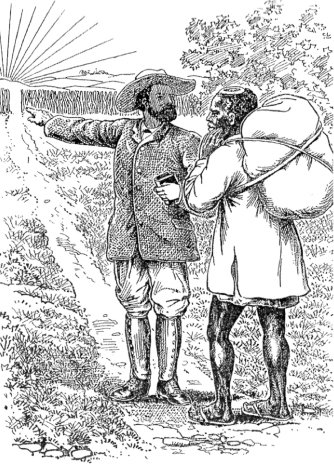

Figure 7. ‘Evangelist points the way’. Illustration by C. J. Montague of ‘Christian’ being given directions by a white missionary (with clothes to match), a favourite motif in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century perceptions. From the Ndebele edition of Bunyan’s

Pilgrim’s Progress,

1902.

There are, then, growing signs of a fuller appreciation of the extent and nature of African oral literature. But even now it is only beginning to be established as a systematic and serious field of study which could co-ordinate the efforts of all those now working in relative isolation. The desultory and uneven nature of the subject still reflects many of the old prejudices, and even recent studies have failed to redress the inherited over-emphasis on bare prose texts at the expense of poetry, or provide any close investigation of the role of composer/poet and the social and literary background. The idea is still all too prevalent—even in some of the better publications—that even if such

literature is after all worthy of study, this can only be so in a ‘traditional’ framework. The motive, then, for the study is partly antiquarian, and haste is urged to collect these items before they vanish or are ‘contaminated’ by new forms. These ‘new’ forms, it is frequently accepted without question, are either not significant enough in themselves to deserve record or, if they are too obvious to evade notice, are ‘hybrid’ and somehow untypical. How misleading a picture this is obvious when one considers the many topical songs recorded by, for instance, the African Music Society, the modern forms of praise poems or prose narratives, oral versions embroidered on Christian hymns, or the striking proliferation of political songs in contemporary Africa—but the old assumptions are still tenacious and time after time dictate the selection and presentation of African oral literature with all the bias towards the ‘traditional’. In keeping with this approach too is the still common idea that African literature consists mainly of rather childish stories, an impression strengthened by the many popular editions of African tales reflecting (and designed to take advantage of) this common idea. Even now, therefore, such literature is often presented and received with an air of condescension and slightly surprised approval for these supposedly naive and quaint efforts. Most prevalent of all, perhaps, and most fundamental for the study of African oral literature is the hidden feeling that this is not really

literature

at all: that these oral forms may, perhaps, fulfil certain practical or ritual functions in that supposedly odd context called ‘tribal life’, but that they have no aesthetic claims, for either local people or the visiting scholar, to be considered as analogous to proper written literature, let alone on a par with it. The idea continues to hold ground that it is

radically

different from real (i.e. written) literature and should even have its own distinctive name (‘folklore’ perhaps) to make this clear. The fact, however, that oral literature can also be considered on its own terms, and, as pointed out in the last chapter, may have its

own

artistic characteristics, analogous to but not always identical with more familiar literary forms, is neglected in both popular conceptions and detailed studies.