Oral Literature in Africa (12 page)

Read Oral Literature in Africa Online

Authors: Ruth Finnegan

The poetic, the topical, and the literary—all these, then, are aspects which still tend to be overlooked. It is indeed hard for those steeped in some of the earlier theories to take full account of them. But what the subject now demands is further investigation of these aspects of African oral art, as well as the whole range of hitherto neglected questions which could come under the general heading of the sociology of literature; and a turning away from the generalized assumptions of earlier theoretical and romanticizing speculators and of past (or even present) public opinion.

Footnotes

1

Written literature, mainly on Arabic models, is further mentioned in Ch. 3; cf. also Ch. 7.

2

For more detailed accounts of the study of oral literature in general (usually under the name of ‘folklore’) see Thompson 1946; Jacobs 1966; Krappe 1930; Dorson, i, 1968; and the more general essays in von Sydow 1948.

3

On this period see Curtin 1965: 392ff.; Greenburg 1965: 432ff.

4

e.g. Casalis 1841 (Sotho), Koelle 1854 (Kanuri), Schlenker 1861 (Temne), Burton 1865 (a re-publication of the collections of others), Bleek 1864 (Hottentot), Callaway 1868 (Zulu), Steere 1870 (Swahili), Christaller 1879 (Twi), Bérenger-Féraud 1885 (Senegambia), Schon 1885 (Hausa), Theal 1886 (Xhosa), Jacottet 1895, 1908 (Sotho), Taylor 1891 (Swahili), Büttner 2 vols., 1894 (Swahili), Chatelain 1894 (Kimbundu), Junod 1897 (Ronga), Dennett 1898 (Fjort), Velten 1907 (Swahili). For further references to works currently considered relevant, see introductions to Chatelain 1894, Jacottet 1908; also Seidel 1896, Basset 1903.

5

Chatelain 1894, p. 20.

6

See e.g. McLaren 1917: 332 (‘how human the Bantu peoples are!’); Smith and Dale ii, 1920: 345 (‘man’s common human-heartedness is in these tales … across the abysses we can clasp hands in a common humanity’); Junod 1938: 57 (‘proof that the

Umuntu

has a soul, and that under his black skin beats a genuine human heart …’, cf. p. 83); etc.

7

e.g. Macdonald 1882 (Yao), Ellis, 1890 (Ewe) 1894 (Yoruba).

8

e.g. Koelle 1854; Macdonald 1882, i, Ch. 2 and pp. 47–57.

9

Cf. also Burton 1865, pp. xiiff; M. Kingsley in introduction to Dennett 1898, p. ix; Seidel 1896 (introduction); Cronise and Ward 1903, p. 4.

10

e.g. Chatelain’s introductory sections in 1894 and Seidel’s general survey in 1896. Cf. also Jacottet 1908 (introduction).

11

See Curtin 1965: 397.

12

Zeitschrift für afrikanische Sprachen

(Berlin, 1887–90), edited by C. G. Büttner;

Zeitschrift für afrikanische und oceanische Sprachen

(Berlin, 1895–1903), edited by A. Seidel;

Zeitschrift für Kolonial-Sprachen

(Berlin), founded in 1910 and, under its present title of

Afrika und Übersee

, still in continuation (at some periods entitled

Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen

). Material on African literature is also included in

Mitteilungen des Seminars für orientalische Sprachen zu Berlin (1989-), Zeitschrift für Ethnologic

(Berlin, 1869-), and

Anthropos

(Salzburg, Vienna, and Fribourg, 1906-); cf. also

Mitteilungen des Instituts für Orientforschung

(Berlin, 1953-).

13

Pointed out by McLaren 1917: 330. Especially Seidel 1896, Meinhof 1911.

14

Especially Seidel 1896, Meinhof 1911.

15

See, among many others, Büttner 1888; Gutmann 1914, 1928, also 1909 and 1927, etc.; A. Seidel, ‘Sprichwörter der Wa-Bondei in Deutsch-Ostafrika’,

ZAOS

4, 1898; 5, 1900, etc.; von Hornbostel 1909; Fuchs 1910; E. Bufe 1914; Hecklinger 1920/1; Ebding 1938 (not seen); and, with Ittmann 1955, 1956; Bender (not seen); Witte 1906, etc. (Ewe); Spiess 1918a, 1918b, 1919; Härtter 1902. German scholars also worked on Hausa and Kanuri in Northern Nigeria, e.g. Prietze 1904, 1916a, 1916b, 1917, 1918, 1927. 1931 (Hausa), 1914 (Kanuri), also 1915, 1930; Lukas 1935, 1937 (Kanuri). See also some of the collections mentioned above.

16

See discussion of this school in Nettl 1956, Ch. 3.

17

e.g. the work by Ittmann and Ebding on Duala and other Cameroons languages, or Dammann on Swahili; cf. also the rather different series of publications by Frobenius 1921–8.

18

Cf. The early university recognition of African languages ad Bantu studies generally, and in particular the influence of C. M. Doke, famous both a linguist and as collector and analyst of oral literature. The south Afircan journal

Bantu Studies

, later entitled

African Studies

(Johannesburg 1921-) is one of the best sources for scholarly and well-informed articles in English on oral literature (mainly but exclusively that of southern Africa).On the contribution of south African Universitie to linguistic studies see Doke in Bantu Studies 7, 1933, pp. 26–8.

19

Till recently, not very developed in England, especially as concerns the oral literature aspect. The School of Oriental Studies (later Oriental and African Studies) of the University of London, founded in 1916, was the main centre of what African linguistic studies there were, but in the early years the African side was little stressed. Some of the better of the articles on African oral literature produced in English on oral literature (mainly but not exclusively that of southern Africa). On the contribution of South African universities to linguistic studies see Doke in

Bantu Studies

7, 1933, pp. 26–8.

20

For a fuller discussion of the effect of these theories on the interpretation of prose narratives, see Ch. 12.

21

e.g. such general works as J. A. MacCulloch

The Childhood of Fiction: a Study of Folk Tales and Primitive Thought

(1905), G. L. Gomme

Folklore as an Historical Science

(1908), A. S. MacKenzie

The Evolution of Literature

(1911—quite a perceptive account, in spite of its evolutionist framework, including some treatment of African oral literature), E. S. Hartland

The Science of Fairy Tales

(1891), J. G. Frazer

Folklore in the Old Testament

(1918), and (in some respects a later survival of evolutionist assumptions) Bowra 1962. Though the detailed theories differ considerably, all share the same basically evolutionist approach.

22

And not just those. See, for example, the contradictions Cope runs into in his otherwise excellent treatment of Zulu praise poetry because of his assumption (undiscussed) that ‘traditional literature’ must be due to ‘communal activity’ (compare pp. 24 and 33, also pp. 53–4, in Cope 1968).

23

e.g. Thompson 1955–8 for the best-known general reference work and, for African material, Klipple 1938 and Clarke 1958. Detailed comparative analyses of particular motifs or plots from African materials, mainly published in Uppsala (Studia ethnographica Upsaliensia), include Abrahamsson 1951; Tegnaeus 1950; Dammann 1961. Cf. also the South African branch of this school, e.g. Hattingh 1944 (

AA

5. 356); Mofokeng 1955.

24

Cf. Boas’s early works on (mainly American-Indian) oral literature, and more recent work relevant to Africa by Herskovits (1936 and 1958) and Bascom (1964, etc.). Some of the best collections of African literature have been published by the American Folk-lore Society (Chatelain 1894, Doke 1927).

25

Cf. Thompson 1946, pp. 396ff.

26

Cf. the excellent critical accounts of this approach in von Sydow 1948, M. Jacobs 1966.

27

e.g. Equilbecq 1913–16, Junod 1912–13, Smith and Dale 1920, Rattray 1930, etc., Green 1948, Carrington 1949

b

, etc., Verger 1957. Cf. also the mammoth general survey by the Chadwicks (1932–40).

28

See particularly the many publications of Doke, and a series of valuable articles in

Bantu Studies

(later

African Studies

); there are also a number of as yet unpublished theses (especially Mofokeng 1955).

29

Paris, 1947-; cf. also many articles in

Black Orpheus

and some in the various IFAN journals; Senghor 1951, etc.; and generalized descriptions such as that in Jahn 1961, Ch. 5.

30

e.g. A. Hampaté Ba (Bambara and Fulani), G. Adali-Mortti (Ewe), Lasebikan (Yoruba), perhaps A. Kagame (Ruanda); cf. also the more general accounts by Colin 1957, Traoré 1958.

31

Notably the Chadwicks’ great comparative study of oral literature which had previously had surprisingly little impact on African studies.

32

See its journal,

African Music

(1954-), and the earlier

Newsletter

(1948-); a library of African music has been built up in Johannesburg; cf. also the work of such scholars as Rhodes and Merriam, and various publications in the journal

Ethnomusicology

. Other musicologists less closely associated with this school but carrying out similar studies include A. M. Jones, Rouget, Nketia, Blacking, Belinga, Carrington, Rycroft, Wachsmann, and Zemp.

33

Some of their work also appears in the main anthropological journals in America.

34

e.g. the well-known work of anthropologists like Boas, Benedict, or Reichard (mainly on American Indian peoples), and more recently Herskovits on Africa and elsewhere. See also the general discussion in Greenway 1964.

35

See especially the bibliographic and other survey articles by Bascom, who is probably doing more than any other single scholar at the present to consolidate the subject as a recognized branch of scholarship, e.g. Bascom 1964, 1965

a

, 1965

b

; cf. also Herskovits 1958, 1961, etc.; Messenger 1959, 1960, 1962; Simmons 1958, 1960

a

, etc. Berry’s useful survey of West African spoken art (1961) draws largely on the findings of this group.

36

That this has not yet gone as far as it might is shown by the very limited recognition of the material of so original a scholar as Nketia, much of whose work has appeared only in local publications.

37

These local scholars include, to mention only a selection, Lasebikan (Yoruba), Abimbola (Yoruba), Owuor (alias Anyumba) (Luo), Mofokeng (Sotho), Nyembezi (Zulu), Hampaté Ba (Fulani), Adali-Mortti (Ewe), Okot (Acholi and Lango).

38

E.g. the somewhat Freudian approaches in Rattray 1930 and Herskovits 1934, or Radin’s more Jungian turn (1952, etc.).

39

An extension both of the functionalist school mentioned earlier and of the ‘structuralist’ approach; see e.g. Beidelman 1961, 1963 (and a number of other articles on the same lines).

40

See the influential and controversial article by C. Lévi-Strauss, ‘The Structural Study of Myth’,

JAF

68, 1955 (not directly concerned with African oral literature but intended to cover it among others); also Dundes 1962; Hamnett 1967. For a useful critique of this approach see Jacobs 1966.

41

Cf. e.g. Arnott 1957, Berry 1961, Andrzejewski 1965, etc., Whiteley 1964, and other work under the auspices of the School of Oriental and African Studies in the university of London.

42

The Oxford Library of African Literature, for instance, (mainly devoted two oral literature) is edited by two anthropologists and a linguist.

43

Notably de Dampierre, Lacroix, and others in the new

Classiques africains

series; cf. also a number of excellent studies in the journal

Cahiers d’études africaines

(Paris, 1960-) and the Unesco series of African texts which has involved the collaboration of a number of scholars, many of them French. As this type of approach interacts with the already established tradition of Islamic and Arabic scholarship in parts of Africa, we may expect further interesting studies in these areas. This has already happened to some extent for indigenous written literature (see e.g. Lacroix 1965, Sow 1966 on Fulani poetry).

44

See especially Vansina 1965, and the general interest in recording texts for primarily historical purposes, e.g. the series of Central Bantu Historical Texts (Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, Lusaka).

3. The Social, Linguistic, and Literary Background

Social and literary background. The linguistic basis—the example of Bantu. Some literary tools. Presentation of the material. The literary complexity of African cultures

.

I

In Africa, as elsewhere, literature is practised in a society. It is obvious that any analysis of African literature must take account of the social and historical context—and never more so than in the case of oral literature. Some aspects of this are discussed in the following chapter on poetry and patronage and in examples in later sections. Clearly a full examination of any one African literature would have to include a detailed discussion of the particularities of that single literature and historical period, and the same in turn for each other instance—a task which cannot be attempted here. Nevertheless, in view of the many prevalent myths about Africa it is worth making some general points in introduction and thus anticipating some of the more glaring over-simplifications about African society.

A common nineteenth-century notion that still has currency today is the idea of Africa as the same in culture in all parts of the continent (or at least that part south of the Sahara); as non-literate, primitive, and pagan; and as unchanging in time throughout the centuries. Thus ‘traditional’ Africa is seen as both uniform and static, and this view still colours much of the writing about Africa.

Such a notion is, however, no longer tenable. In the late nineteenth or earlier twentieth centuries (the period from which a number of the instances here are drawn) the culture and social forms of African societies were far from uniform. They ranged—and to some extent still do—from the small hunting

bands of the Bushmen of the Kalahari desert, to the proud and independent pastoral peoples of parts of the Southern Sudan and East Africa, or the elaborate and varied kingdoms found in many parts of the continent, above all in western Africa and round the Great Lakes in the east. Such kingdoms provided a context in which court poetry and court poets could nourish, and also in some cases a well-established familiarity with Arabic literacy. Again, in the economic field, almost every gradation can be found from the near self-sufficient life of some of the hunting or pastoral peoples to the engagement in far-reaching external trade based on specialization, elaborate markets, and a type of international currency, typical of much of West Africa and the Arab coast of East Africa. The degree of specialization corresponding to these various forms has direct relevance to the position of native composers and performers of oral literature—in some cases leading to the possibility of expert and even professional poets, and of a relatively leisured and sometimes urban class to patronize them. In religion again, there are many different ‘traditional’ forms: the older naive pictures of Africa as uniformly given up to idol-worshipping, fetishes, or totemism are now recognized as totally inadequate. We find areas (like the northerly parts of the Sudan region and the East Coast) where Islam has a centuries-long history; the elaborate pantheons of West African deities with specialized cults and priests to match; the interest in ‘Spirit’ issuing in a special form of monotheism among some of the Nilotic peoples; the blend between belief in the remote position of a far off ‘High God’ and the close power of the dead ancestors in many Bantu areas—and so on. This too may influence the practice of oral art, sometimes providing the context and occasion for particular forms, sometimes the need for expert religious performers.

In some areas we also find a long tradition of Arabic literacy and learning. The east coast and the Sudanic areas of West Africa have seen many centuries of Koranic scholarship and of specialist Arabic scribes and writers using the written word as a tool for correspondence, religion, and literature. To an extent only now being fully realized, these men were responsible for huge numbers of Arabic manuscripts in the form of religious treatises, historical chronicles, and poetry.

1

In fact, even for earlier centuries a nineteenth-century writer on Arabic literature in the Sudan region as a whole can sum up his work:

On peut conclure que, pendant les XIV

e

, XV

e

et XVI

e

siècles, la civilisation et les sciences florissaient au même degré sur presque tous les points du continent que nous étudions; qu’il n’existe peut-être pas une ville, pas une oasis, qu’elles n’aient marquée de leur empreinte ineffaçable, et surtout, que

la race noire n’est pas fatalement réleguée au dernier échelon de l’espèce humaine

(Cherbonneau 1856: 42)

Not only was Arabic itself a vehicle of communication and literature, but many African languages in these areas came to adopt a written form using the Arabic script. Thus in the east we have a long tradition of literacy in Swahili and in the west in Hausa, Fulani, Mandingo, Kanuri, and Songhai. With the exception of Swahili,

2

the native written literature in these languages has not been very much studied,

3

but it seems to be extensive and to include historical and political writings in prose, theological treatises, and long religious and sometimes historical poems. The literary models tend to be those of Arabic literature, and at times paraphrase or even translation seem to have been involved. In other cases local literary traditions have been built up, like the well-established Swahili literature, less directly indebted to Arabic originals but still generally influenced by them in the form and subject-matter of their writings.

In stressing the long literate tradition in certain parts of Africa, we must also remember that this was the preserve of the specialist few and that the vast majority even of those peoples whose languages adopted the Arabic script had no direct access to the written word. In so far as the writings of the scholars reached them at all, it could only be by

oral

transmission. Swahili religious poems were publicly intoned for the enlightenment of the masses (Harries 1962: 24), Fulani poems declaimed aloud (Lacroix i, 1965: 25), and Hausa compositions like ‘the song of Bagaudu’ (Hiskett 1954: 550) memorised in oral form. The situation was totally unlike the kind of mass literacy accompanied by the printing press with which we are more familiar.

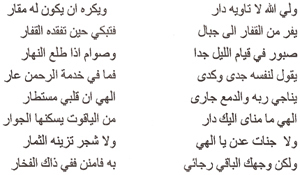

Figure 8. Arabic script of a nineteenth-century poem in Somali (from B. W. Andrzejewski ‘Arabic influence in Somali poetry’ in Finnegan et al 2011).

Besides Arabic forms, there are a few other instances of literate traditions in Africa. These include the now obsolete

tifinagh

script of the Berber peoples of North Africa, among them the Tuareg of the Sahara. Here the written form was probably little used for literary composition, but its existence gave rise to a small lettered class and the interplay between written and oral traditions. Most often it was the women, staying at home while the men travelled, who composed the outstanding panegyric, hortatory, and love poetry of this area.

4

More important is the long written tradition of Ethiopia. This is the literature of a complex and ancient civilization whose association with Christianity probably dates back to about the fourth century. Though probably never in general use, writing was used from an early period. It occurs particularly in a Christian context, so that the history of Ethiopic written literature coincides pretty closely with Christian literature, much of it based on translation. There are chronicles (generally taking the Creation of the World as their starting-point), lives of the saints, and liturgical verse. In addition there are royal chronicles which narrate the great deeds of various kings.

5

The few other minor instances of indigenous scripts for local languages, such as Vai, are of little or no significance for literature and need not be considered here.

The common picture, then, which envisages all sub-Saharan Africa as totally without letters until the coming of the ‘white man’ is misleading. Above all it ignores the vast spread of Islamic and thus Arabic influences over many areas of Africa, profoundly affecting the culture, religion, and literature. It must be repeated, however, that these written traditions were specialist ones unaccompanied by anything approaching mass literacy. The resulting picture is sometimes of a split between learned (or written) and popular (or oral) literature. But in many other cases we find a peculiarly close interaction between oral and written forms. A poem first composed and written down, for instance, may pass into the oral tradition

and be transmitted by word of mouth, parallel to the written form; oral compositions, on the other hand, are sometimes preserved by being written down. In short, the border-line between oral and written in these areas is often by no means clear-cut.

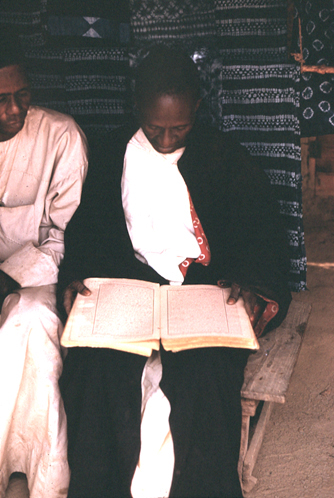

Figure 9. Reading the Bible in up-country Sierra Leone, 1964 (photo David Murray).

The earlier belief that Africa had no history was due to ignorance. Africa is no exception to the crowded sequence of historical events, even though it is only recently that professional historians have turned their attention to this field.

The early impact and continuing spread of Islam, the rise and fall of empires and kingdoms throughout the centuries, diplomatic or economic contacts and contracts within and outside Africa, movement and communication between different peoples, economic and social changes, wars, rebellions, conquests, these are all the stuff of history. No doubt too there have been in the past, as in the present, rising and falling literary fashions, some short-lived, others long-lasting; some drawing their inspiration from foreign sources, others developing from existing local forms. Examples in this volume may give a rather static impression, as if certain ‘traditional’ forms have always been the same throughout the ages; but such an impression is misleading and arises more from lack of evidence than from any necessary immobility in African oral art. Unfortunately there are few if any African societies whose oral literature has been thoroughly studied and recorded even at one period of time, let alone at several periods.

6

But with increasing interest in oral art it may be hoped that enough research will be undertaken to make it feasible, one day, to write detailed literary and intellectual histories of particular cultures.

A further consequence of the facile assumptions about lack of change in Africa until very recently is to lead one to exaggerate the importance of these more recent changes. To one who thinks African society has remained static for, perhaps, thousands of years, recently induced changes must appear revolutionary and upsetting in the extreme. In fact, recent events, important as they are, can be better seen in perspective as merely one phase in a whole series of historical developments. As far as oral literature and communication are concerned, the changes over the last fifty or hundred years are not so radical as they sometimes appear. It is true that these years have seen the imposition and then withdrawal of colonial rule, of new forms of administration and industry, new groups of men in power, and the introduction and spread of Western education accompanied by increasing reliance written forms of communication. But the impact of all this on literature can be over-emphasized. For one thing, neither schools nor industrial development have been evenly spread over the area and many regions have little of either. There is nowhere anything approaching mass literacy. Indeed it has been estimated that some like eight out of ten adults still cannot read or write

7

and where mass primary education

is the rule it will still take years to eradicate adult illiteracy. Bare literacy, furthermore, in what is often a foreign language (e.g. English or French) may not at all mean that school leavers will turn readily to writing as a form of communication, far less as a vehicle of literary expression. Literacy, a paid job, even an urban setting need not necessarily involve repudiation of oral forms for descriptive or aesthetic communication.

There is a tendency to think of two distinct and incompatible types of society (traditional’ and ‘modern’, for instance), and assume that the individual must pass from one to the other by a sort of revolutionary leap. But individuals do not necessarily feel torn between two separate worlds; they exploit the situations in which they find themselves as best they can. There is indeed nothing to be surprised at in a continuing reliance on oral forms. Similarly there is nothing incongruous. in a story being orally narrated about, say, struggling for political office or winning the football pools, or in candidates in a modern election campaign using songs to stir up and inform mass audiences which have no easy access to written propaganda. Again, a traditional migration legend can perfectly well be seized upon and effectively exploited by nationalist elements for their own purposes to bring a sense of political unity among a disorganized population, as in Gabon in the late 1950s.

8

University lecturers seek to further their own standing by hiring praise singers and drummers to attend the parties given for their colleagues to panegyricize orally the virtues of hosts and guests.