Oral Literature in Africa (5 page)

Read Oral Literature in Africa Online

Authors: Ruth Finnegan

Acknowledgements: Addendum 2012

A slightly abridged version of Chapter 1 appeared in Finnegan 2007. As before, Ibadan Library’s Africana collection, the Doke collection in southern Africa and the blessedly summer-opening libraries of the great universities of southern England have played their indispensible part. So too have national and international conferences, and the innumerable students and scholars in between who have followed up this work. I am also much indebted to the scholars who have commented on the new Preface and added their suggestions of references and website or supplemented the additional resources for this volume (

www.oralliterature.org/OLA

), among them Jeff Opland, Russell Kaschula, Bob Cancel, Ursula Baumgardt and Jean Derive (the last two the more welcome as the first edition was coloured more by English than French scholarship) and Harold Scheub.

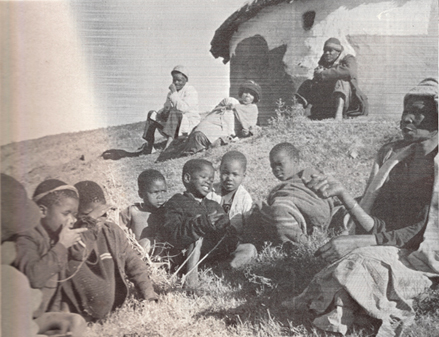

Unlike the first edition, when I do not think the Clarendon Press would have welcomed suggestions of images, this edition contains illustrations. They are of variable quality, location and date (though some date back to the period when the first edition was being written, or reflect the fieldwork that so influenced my approach). Some are from earlier still. But they should at least serve to remind us of the multi-sensory nature of African oral literatures—realised not just in text but in performance and individual artisty.

Old Bletchley, UK, 2012

Abbreviations

Besides the normal abbreviations conventional in scholarly discourse the following abbreviations have been used:

AA | African Abstracts |

Afr. (in journal title) | African/africain(e)(s) [etc]. |

Aft. u. Übersee | Afrika und Übersee |

Am. Anthrop | American Anthropologist |

AMR AC | Musée royal de I’Afrique centrale. Annales (sciences humaines) |

AMRCB | Musée royal du Congo beige. Annales (sciences humaines) |

AMRCB-L | Musée royal du Congo beige. Annales (sciences de I’homme, linguistique) |

Ann. et mém. Com ét. AOF | Annuaire et memoires du Comite d’études historiques et scientifiques de I’AOF |

Anth. Ling | Anthropological Linguistics |

Anth. Quart | Anthropological Quarterly |

ARSC | Académie royale des sciences coloniales (sciences morales) |

ARSOM | Brussels. Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer. Mémoires |

ARSOM Bull | Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer. Bulletin des séances |

BSO(A)S | Bulletin of the School of Oriental (and African) Studies |

Bull. Com. et. AOF | Bulletin du Comité d’études historiques et scientifiques de l’AOF |

Bull. IF AN (B) | Institut français d’Afrique noire Bulletin (serie B) |

Cah. étud. afr | Cahiers d’études africaines |

CEPSI | Bulletin trimestriel du Centre d’étude des problèmes sociaux indigènes |

IAI | International African Institute |

IFAN | Institut français d’Afrique noire |

IRCB Bull | Institut royal colonial beige. Bulletin des séances |

IRCB Mem | Institut royal colonial beige |

JAF | Journal of American Folklore |

JRAI | Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute |

J. Soc. africanistes Mem | Journal de la Société des africanistes |

IFAN | Institut français d’Afrique noire |

Mitt. Inst. Orientforsch | Mitteilungen des Instituts für Orientforschung |

MSOS | Mitteilungen des Seminars für orientalische Sprachen zu Berlin |

OLAL | Oxford Library of African Literature |

Rass. studi etiop | Rassegna di studi etiopici |

SOAS | School of Oriental and African Studies University of London. |

SWJA | Southwestern Journal of Anthropology |

TMIE | Travaux et mémoires de l’Institut d’ethnologie |

Trans. Hist. Soc. Ghana | Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana |

ZA(O)S | Zeitschrift für afrikanische (und oceanische) Sprachen |

ZES | Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen |

ZKS | Zeitschrift für Kolonial-Sprachen |

Note on Sources and References

Only the more obvious sources have been used. Where I have come across unpublished material I have taken account of it but have not made a systematic search. The sources are all documentary with the exception of some comments arising from fieldwork among the Limba of Sierra Leone and a few points from personal observation in Western Nigeria; gramophone recordings have also occasionally been used. In general, I have tried not to take my main examples from books that are already very easily accessible to the general reader. I have, for instance, given references to, but not lengthy quotations from, the ‘Oxford Library of African Literature’ series or the French ‘Classiques africains’.

In time, I have not tried to cover work appearing after the end of 1967 (though references to a few 1968 publications that I happen to have seen are included). This means that the book will already be dated by the time it appears, but obviously I had to break off at some point.

References are given in two forms: (1) the general bibliography at the end, covering works I have made particular use of or consider of particular importance (referred to in the text merely by author and date); and (2) more specialized works not included in the general bibliography (full references given ad loc.). This is to avoid burdening the bibliography at the end with too many references of only detailed or secondary relevance. With a handful of exceptions I have seen the works I cite. Where this is not so, I have indicated it either directly or by giving the source of the reference in brackets. Where I have seen an abstract but not the article itself, this is shown by giving the volume and number of

African Abstracts (AA)

in brackets after the reference.

The bibliography and references are only selective. It would have been out of the question to have attempted a comprehensive bibliography.

I. INTRODUCTION

1. The ‘Oral’ Nature of African Unwritten Literature

The significance of performance in actualization, transmission, and composition. Audience and occasion. Implications for the study of oral literature. Oral art as literature

.

Africa possesses both written and unwritten traditions. The former are relatively well known—at any rate the recent writings in European languages (much work remains to be publicized on earlier Arabic and local written literatures in Africa). The unwritten forms, however, are far less widely known and appreciated. Such forms do not fit neatly into the familiar categories of literate cultures, they are harder to record and present, and, for a superficial observer at least, they are easier to overlook than the corresponding written material.

The concept of an

oral

literature is an unfamiliar one to most people brought up in cultures which, like those of contemporary Europe, lay stress on the idea of literacy and written tradition. In the popular view it seems to convey on the one hand the idea of mystery, on the other that of crude and artistically undeveloped formulations. In fact, neither of these assumptions is generally valid. Nevertheless, there are certain definite characteristics of this form of art which arise from its oral nature, and it is important at the outset to point to the implications of these. They need to be understood before we can appreciate the status and qualities of many of these African literary forms.

It is only necessary here to speak of the relatively simple oral and literary characteristics of this literature. I am not attempting to contribute to any more ambitious generalized theory of oral literature in terms of its suggested stylistic or structural characteristics

1

or of the particular

type of mentality alleged to go with reliance on oral rather than written communication.

2

These larger questions I leave on one side to concentrate on the more obvious properties of unwritten literature.

3

Figure 3. Nongelini Masithathu Zenani, Xhosa story-teller creating a dramatic and subtle story (photo Harold Scheub).

I

There is no mystery about the first and most basic characteristic of oral literature—even though it is constantly overlooked in collections and analyses. This is the significance of the actual performance. Oral literature is by definition dependent on a performer who formulates it in words on a specific occasion—there is no other way in which it can be realized as a literary product. In the case of

written

literature a literary work can be

said to have an independent and tangible existence in even one copy, so that questions about, say, the format, number, and publicizing of other written copies can, though not irrelevant, be treated to some extent as secondary; there is, that is, a distinction between the actual creation of a written literary form and its further transmission. The case of oral literature is different. There the connection between transmission and very existence is a much more intimate one, and questions about the means of actual communication are of the first importance—without its oral realization and direct rendition by singer or speaker, an unwritten literary piece cannot easily be said to have any continued or independent existence at all. In this respect the parallel is less to written literature than to music and dance; for these too are art forms which in the last analysis are actualized in and through their performance and, furthermore, in a sense depend on repeated performances for their continued existence.

The significance of performance in oral literature goes beyond a mere matter of definition: for the nature of the performance itself can make an important contribution to the impact of the particular literary form being exhibited. This point is obvious if we consider literary forms designed to be delivered to an audience even in more familiar literate cultures. If we take forms like a play, a sermon, ‘jazz poetry’, even something as trivial as an after-dinner witty anecdote—in all these cases the actual delivery is a significant aspect of the whole. Even though it is true that these instances may

also

exist in written form, they only attain their true fulfilment when actually performed.

The same clearly applies to African oral literature. In, for example, the brief Akan dirge

Amaago, won’t you look?

Won’t you look at my face?

When you are absent, we ask of you.

You have been away long: your children are waiting for you (Nketia 1955: 184)

the printed words alone represent only a shadow of the full actualization of the poem as an aesthetic experience for poet and audience. For, quite apart from the separate question of the overtones and symbolic associations of words and phrases, the actual enactment of the poem also involves the emotional situation of a funeral, the singer’s beauty of voice, her sobs, facial expression, vocal expressiveness and movements (all indicating the sincerity of her grief), and, not least, the musical setting of the poem. In fact, all the variegated aspects we think of as contributing to the effectiveness

of performance in the case of more familiar literary forms may also play their part in the delivery of unwritten pieces—expressiveness of tone, gesture, facial expression, dramatic use of pause and rhythm, the interplay of passion, dignity, or humour, receptivity to the reactions of the audience, etc., etc. Such devices are not mere embellishments superadded to the already existent literary work—as we think of them in regard to written literature—but an integral as well as flexible part of its full realization as a work of art.

Unfortunately it is precisely this aspect which is most often overlooked in recording and interpreting instances of oral literature. This is partly due, no doubt, to practical difficulties; but even more to the unconscious reference constantly made by both recorders and readers to more familiar written forms. This model leads us to think of the

written

element as the primary and thus somehow the most fundamental material in every kind of literature—a concentration on the

words

to the exclusion of the vital and essential aspect of performance. It cannot be too often emphasized that this insidious model is a profoundly misleading one in the case of oral literature.

This point comes across the more forcibly when one considers the various resources available to the performer of African literary works to exploit the oral potentialities of his medium. The linguistic basis of much African literature is treated in Chapter 3; but we must at least note in passing the striking consequences of the highly tonal nature of many African languages. Tone is sometimes used as a structural element in literary expression and can be exploited by the oral artist in ways somewhat analogous to the use of rhyme or rhythm in written European poetry. Many instances of this can be cited from African poetry, proverbs, and above all drum literature. This stylistic aspect is almost completely unrepresented in written versions or studies of oral literature, and yet is clearly one which can be manipulated in a subtle and effective way in the actual process of delivery (see Ch. 3). The exploitation of musical resources can also play an important part, varying of course according to the artistic conventions of the particular genre in question. Most stories and proverbs tend to be delivered as spoken prose. But the Southern Bantu praise poems, for instance, and the Yoruba hunters’

ijala

poetry are chanted in various kinds of recitative, employing a semi-musical framework. Other forms draw fully on musical resources and make use of singing by soloist or soloists, not infrequently accompanied or supplemented by a chorus or in some cases instruments. Indeed, much of what is normally classed as poetry in African oral literature is designed to

be performed in a musical setting, and the musical and verbal elements are thus interdependent. An appreciation, therefore, of these sung forms (and to some extent the chanted ones also) depends on at least some awareness of the musical material on which the artist draws, and we cannot hope fully to understand their impact or subtlety if we consider only the bare words on a printed page.

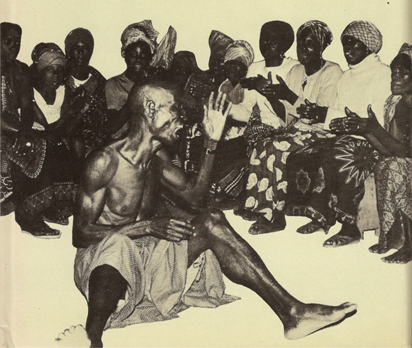

In addition the performer has various visual resources at his disposal. The artist is typically face to face with his public and can take advantage of this to enhance the impact and even sometimes the content of his words. In many stories, for example, the characterization of both leading and secondary figures may appear slight; but what in literate cultures must be written, explicitly or implicitly, into the text can in orally delivered forms be conveyed by more visible means—by the speaker’s gestures, expression, and mimicry. A particular atmosphere—whether of dignity for a king’s official poet, light-hearted enjoyment for an evening story-teller, grief for a woman dirge singer—can be conveyed not only by a verbal evocation of mood but also by the dress, accoutrements, or observed bearing of the performer. This visual aspect is sometimes taken even further than gesture and dramatic bodily movement and is expressed in the form of a dance, often joined by members of the audience (or chorus). In these cases the verbal content now represents only one element in a complete opera-like performance which combines words, music, and dance. Though this extreme type is not characteristic of most forms of oral literature discussed in this volume, it is nevertheless not uncommon; and even in cases where the verbal element seems to predominate (sometimes in co-ordination with music), the actual delivery and movement of the performer may partake of something of the element of dancing in a way which to both performer and audience enhances the aesthetic effectiveness of the occasion.

Much more could be said about the many other means which the oral performer can employ to project his literary products—his use, for instance, of vivid ideophones or of dramatized dialogue, or his manipulation of the audience’s sense of humour or susceptibility (when played on by a skilled performer) to be amazed, or shocked, or moved, or enthralled at appropriate moments. But it should be clear that oral literature has somewhat different potentialities from written literature, and additional resources which the oral artist can develop for his own purposes; and that this aspect is of primary significance for its appreciation as a mode of aesthetic expression.

Figure 4. Mende performer, Sierra Leone, 1982. Note the performer’s gestures and the clapping audience/chorus, essential for the performance (photo Donald Cosentino).

The detailed way in which the performer enacts the literary product of his art naturally varies both from culture to culture and also among the different literary genres of one language. Not all types of performance involve the extremes of dramatization. Sometimes indeed the artistic conventions demand the exact opposite—a dignified aloof bearing, and emphasis on continuity of delivery rather than on studied and receptive style in the exact choice of words. This is so, for instance, of the professional reciter of historical Rwanda poetry, an official conscious of his intellectual superiority over amateurs and audience alike:

Contrairement à l’amateur, qui gesticule du corps et de la voix, le récitant professionnel adopte une attitude impassible, un débit rapide et monotone. Si 1’auditoire réagit en riant ou en exprimant son admiration pour un passage particulièrement brillant, il suspend la voix avec détachement jusqu’à ce que le silence soit rétabli.

(Coupez and Kamanzi 1962: 8)

This might seem the antithesis of a reliance on the arts of performance for the projection of the poem. In fact it is part of this particular convention

and, for the audience, an essential part. To this kind of austere style of delivery we can contrast the highly emotional atmosphere in which the southern Sotho praise poet is expected to pour out his panegyric. Out of the background of song by solo and chorus, working up to a pitch of excitement and highly charged emotion,

the chorus increases in its loudness to be brought to a sudden stop with shrills of whistles and a voice (of the praise poet) is heard: ‘Ka-mo-hopola mor’a-Nyeo!’ (I remember the son of so-and-so!)

Behind that sentence lurks all the stored up emotions and without pausing, the name … is followed by an outburst of uninterrupted praises, save perhaps by a shout from one of the listeners: ‘Ke-ne ke-le teng’ (I was present) as if to lend authenticity to the narration. The praiser continues his recitation working himself to a pitch, till he jumps this way and that way while his mates cheer him … and finally when his emotion has subsided he looks at his mates and shouts: ‘Ntjeng, Banna’ (lit. Eat me, you men). After this he may burst again into another ecstasy to be stopped by a shout from him or from his friends: ‘Ha e nye bolokoe kaofela!’ or ‘Ha e nye lesolanka!’ a sign that he should stop.