Outposts (14 page)

And then we bump against the rusty hull of the RMS

St Helena

, and clamber up the ladder, and the dinghy turns away with a whoop and a wave from the men aboard. And, with a speed and a suddenness that is as kind as it seems brutal, we sound our valedictory sirens, the telegraphs clang to full ahead, and the island, a tiny cone of rock set in a wild and heaving sea, recedes to a mere shadow in the sky, and then a speck on the horizon, and then but a memory.

Behind us, night and day, gale or calm, for a thousand miles and more flies a great white albatross, a bird that was probably born in the Tristan islands, and is amusing herself by following us, her adopted, sea-bound friends below. But then as we draw near the African coast she suddenly turns and wheels away, and soars up into the leaden skies, back to the lonely mysteries of the South Atlantic, to her companions of the colony set far from everywhere, and utterly alone. And when she has vanished in the great empty skies, I know all my links with Tristan have been severed, and that the most difficult and longest of the journeys is done.

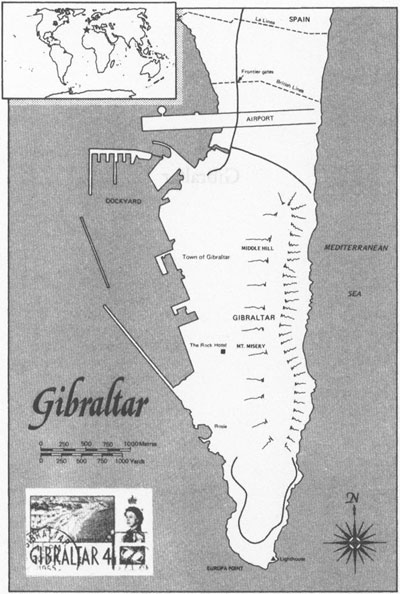

Gibraltar

Gibraltar

‘This dark corner of the world’, Lord Nelson had called Gibraltar. It was a prophetic remark, for it was to Gibraltar, and to the old circular harbour at Rosia at the southern tip of the peninsula, that the Admiral’s body was carried after Trafalgar. He had been pickled in cognac, because there was not enough rum on the

Victory

, and the barrel blew up in the October heat: so at Gibraltar the Navy repaired the damage and loaded his remains back on board his flagship which then, to the beat of muffled drums, set sail again for the sad passage to Greenwich, and the January funeral and the burial in the crypt of St Paul’s.

All the elements of the Rock’s use and meaning are encapsulated in this sad vignette from Imperial history. Gibraltar was, and is, a naval base. Without Gibraltar Britain would quite probably have lost Trafalgar, and Napoleon might have made the British Isles a part of his own French Empire, and never been forced to the ignominy of exile on St Helena. It was, and is, a place for repair, for the treatment of injury, the destination of the dying and the dead. It was, and is, a place of miserable weather, of heat and humidity, of distemper and ill-health. It was, and is, a place of necessity rather than of glory, a place to use rather than to like, a symbol of might and power and domain and steadfastness, a place all utilitarian, and not at all romantic.

And above all, as Nelson scribbled in his log, and as others have noted since, it is a brooding, frowning place, its character delineated and dominated by its towering atmosphere of darkness.

Laurie Lee had it perfectly. He had walked there in the Thirties (all the way from the Cotswolds, in fact) and first saw Gibraltar from the top of a hill behind Algeciras.

Africa, Spain and the great sweep of the Bay all shone with a fierce bronze light. But not Gibraltar; it lay apart like an interloper, as though it had been towed out from Portsmouth and anchored off-shore, still wearing its own grey roof of weather. Slate-coloured, aloof, surrounded by a scattering of warships and fringed by its dockyard cranes, the Rock lay shadowed beneath a plate of cloud, immersed in a private rainstorm.

One recent summer’s day I made my own plans to visit the Rock, which involved approaching it over much the same route, through the hills and on the clifftops of Andalucia. From London I telephoned the Governor’s office at the Convent, Gibraltar (the exchange was called, appropriately, ‘Fortress’). A date was suggested, teatime said to be most suitable, punctuality said to be important since the Governor was a navy man. I flew to San Pablo airport in Sevilla, drove to Cadiz and, after arming myself with a compass, a sheaf of Spanish army maps, a canteen, a stout hazel stick and a foot repair kit, set off to march around the most southerly bastion of Europe to see Britain’s only remaining colony on the Continent. (Britain’s European possessions have never been numerous, despite convenience and closeness. She had Heligoland in the North Sea, and from Port Mahon in Minorca the Royal Navy ran the Balearic Islands. There were the Ionian Islands, and Malta, of course, and Cyprus (though hardly a European possession). And the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, which are not colonies, but direct dependencies of the Crown and lie outside the United Kingdom. Gibraltar is the only unquestioned European colony that remains, and is definitely the only British Imperial possession that there ever has been on the continent of Europe itself.)

It took the best part of a week to climb up from the valley of the Guadalquivir to the limestone mountain chain of which Gibraltar was an outlier. I had to pass through tuna-fishing villages, where I would sip ice-cold

fino

and discuss the price of albacore; I stopped for half a day to inspect the great lighthouse at Cape Trafalgar—where it turned out that only one of a dozen Andalucians I questioned had ever heard of Nelson, or Villeneuve, most Spaniards evidently preferring to linger on Spain’s victories rather than her

defeats. I climbed to the Moorish town of Vejer de la Frontera, and looked down across the fog-filled Straits to see the brown rumps of the Rif mountains, in Africa; and then came closer still to the great continent by marching along the mole in Tarifa, and thus becoming briefly the southernmost inhabitant of Europe. But then I was stopped and turned back by a menacing-looking Spanish soldier; the Campo de Gibraltar, along with the Balearics and the Canaries, is one of Spain’s three principal military zones, crawling with soldiery who are there to show Spain’s determination to protect the vital Straits, and to remind the British that the Crown colony of Gibraltar long has been, still is and always will be claimed by the people of Spain. I was sorry to have to leave the quayside, for there was a most dramatic illustration of the separation of the waters of Atlantic and Mediterranean; on the western side of the mole the water was green and wind-whipped, rose and fell with a long oceanic swell, and looked quite cold; on the eastern inner side the sea was blue and calm, looked warm, and was littered with all the floating debris of the little town.

It was before dawn—deliciously cool, and the best time for a summer’s walk through Andalucia—when I breasted the hill above Algeciras. The old port’s lights twinkled and blinked below, and there were pricks of riding lanterns on the ships at anchor in the Roads. The bay, I could just make out, was a vast semicircle, the lowlands and the refineries to the left, the open sea, and a dusty glimmer of Africa, to the right.

And on the far side, rising like a long and ragged wall of steel, battleship-grey and ready for war, was the Rock. It was indeed, as Laurie Lee had noted, dark and separate from the land beside—rather sinister, rather magnificent. And then, just at that moment, sliding up and over it like a Barbary corsair’s scimitar, was the morning sun. As it rose so the colours changed, from deep burnt orange through gold to the brassy yellow of a Spanish summer day. And as the sunlight became ever more intense, so Gibraltar faded into a rising heat haze, her grey and forbidding aspect becoming muted and pale, and then vanishing altogether into the background blue.

It was a little after seven, and tea at the Convent was at four o’clock sharp. I marched down into Algeciras, crossed the two small rivers, de las Cañas and Guadarranque, hurried under the belching pipework of the refineries at El Mirador and, with the immense wall of the Rock rearing white above me—a Union flag fluttering, proud and familiar, from a summit pole—walked past the shops of La Linea to the frontier.

My watch said almost three, the sun was very hot. But by my reckoning I was now only about two miles from my destination—the old Franciscan friary that had been counting house and Governor’s residence from the first days of Imperial occupation. (It is called ‘the Convent’, but has never housed nuns. King Edward VII thought it an undignified name and had it changed to ‘Government House’ but in 1943 his grandson, George VI, ordered it changed back.) It should have been no problem.

But the couple of miles turned out to be considerably longer, and more costly, than I had supposed. The eccentricities of global politics took over at this point, and what I had expected would be simply a matter of frontier formalities turned into a protracted and amusing farce.

The border was marked by a gate—two pairs of gates, actually, parallel, policing the same entrance, and no more than three inches from each other. The inner gate was clearly the British gate—it was made of black iron, and had limestone pillars, topped with cannonballs. It was wide open.

The other gate—the nearer to Spain, and thus nearer to me—was more modern, made of green-painted steel. Festooned with a ganglion of bolts and padlocks, it was very firmly closed. Beside it was a platoon of Spanish soldiers, and a detachment of the Policía Nacional.

Beyond the two gates lay a territory that was manifestly British. There were two policemen, kitted out exactly as their colleagues in Kensington and Chelsea. The Gibraltar Police, I had read, are the oldest colonial force, formed soon after Robert Peel raised the Metropolitan in London. They have been quite severely criticised by the Gibraltarians for being too timid and gentle. There was a

flagpole with a large Union flag, lazily undulating in the warm breeze. Beside it were two brass cannon, and polishing them a group of half-stripped British infantrymen—members of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment; a couple of their colleagues, in full uniform and holding rifles, stood to attention outside the sentry-posts. Every few moments one would stamp about loudly, and there would be great clatter and drama as he paced out his brief ceremonial route. Then the site would fall silent, except for a murmur of grumbles from the soldiers polishing the guns, and the distant whine of jet engines as a fighter, or perhaps a civil airliner, readied itself for take-off from the runway close behind.

Teatime was near, and I beckoned to one of the policemen. I gave my name, explained that I had an appointment with His Excellency in half an hour, and suggested he might check. He disappeared into his blockhouse, and returned a moment later with a grin. Yes, he said, the Convent was expecting me; the kettle, he implied, was on. Fine, I said—can I come in?

There was a cough, and an embarrassed silence. Policemen looked at soldiers, at me, at the Spanish soldiers—who lounged around, stretching and scratching themselves, and yawning, until every few minutes, when an officer would bellow some unintelligible order and the squad would fall in, brace themselves and march up and down before the gates, their feet clattering unevenly in amiable disagreements over the step. The constable was indeed both gentle and timid in his reply. Yes, he ventured, I was most welcome, and a car would be provided to hurry me into town. But there might be problems with this gentleman approaching. And as I looked round a tall fellow in the brown and black of the National Police was advancing; he smiled warmly, and begged my pardon (he had trained as a hotel manager in Brighton, it seems, before joining the force), but could he possibly have the pleasure of seeing my passport?

Since my arrival at the gate and the attempt to pass through had been in the nature of an experiment I cannot say I was surprised by what happened, though, since I was quite footsore and eager for a cup of tea, I was irritated. The policeman told me firmly that as a

British passport holder I could not, he was sorry to say, cross into the colony by road. If I wanted to visit this charming corner of Spain—he would not accept that its occupation was anything more than temporary—I would have to trek back to Algeciras, take the next hydrofoil to Tangier, and take another similar (in fact, as it turned out, the very same) craft back from Tangier to Gibraltar. In other words I could travel the three inches with pleasure, but only after having made brief obeisance in a third, neutral country, in Africa. It all suddenly seemed rather ludicrous, and I was cross that I was going to be late for tea. (Afternoon tea is not the only British custom still rigorously maintained in the colony. The author Nicholas Luard once met a formidable British nanny near Algeciras. In spite of the heat she was dressed in a severe grey coat and skirt, and wore a grey felt hat, and very sensible shoes, in which she was clumping towards La Linea. Luard offered her a lift, and asked where she was going. ‘Gibraltar,’ she replied, in tones impeccably Home Counties, ‘to buy a reliable kipper.’)

In the event, the excursion was pleasant enough, even though the bullet-like craft only narrowly escaped being run over by a tanker in the thick fog—the cotton-wool-like

taro

—that hangs almost perpetually over the Straits. Our captain, a fat and unshaven Moor, weaseled his machine deftly under the approaching bow, and let fly a string of colourful imprecations at the wall of rusty steel above us. The fog thinned, the roar of the motor settled to a dignified chug, and out of the haze ahead, below the crouching-lion shape of the Rock herself, was the stone magnificence of the old dockyards—the former home of the Royal Navy’s Atlantic Fleet, built for the Admiralty by Messrs. Topham, Jones and Railton, to be the undisputed and ostentatious guardian of the Straits, the Mediterranean, and the route to the Orient. While Bermuda guarded the Atlantic, Simonstown and Trincomalee—‘Trinco’ to the sailors—looked after the Indian Ocean, and Singapore, Hong Kong and Weihaiwei were home to the China Squadrons, so Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria and Aden preserved the integrity of the most vital of all Imperial waterways—the route to India. Small wonder, then, the

sound of bugles from the dockside barracks sounded like a declaration of Imperial intent to any passing strangers: What We Have, they seemed to say, We Hold.

From Trafalgar to the Falklands, from the Malta convoys to the Suez invasion, the dockyards of Gibraltar have long been vital for naval assembly, organisation, coaling, victualling, the loading of munitions and the making of war. Every fleet and every warship of naval note has been there—the

Hood

, the

Nelson

, the

Rodney

and, of course, the

Victory

on her mournful mission. When the Home and the Mediterranean Fleets met in the harbour in 1939, as they would do for spring manoeuvres every year before the war, the bay was an almost solid mass of grey steel, and 200 funnels belched smoke into the sky.

But on this summer morning I could only see the funnel of a single frigate, and the upperworks of another naval vessel, even tinier, buried deep in one of the drydocks. A fellow-passenger, a Gibraltarian, told me that the fleets made little use of Gibraltar now (‘though it was very exciting during the Falklands War. Just like the old days!’) and at the beginning of the Eighties the Admiralty, in a decision that had caused bitter anguish among the Gibraltarians, had decided to sell the dockyards. A private firm, which had promised to employ most of the workforce, was going to try to turn a profit from commercial ship-repairing, but no one was very optimistic. (Gibraltar is now suffering the consequences of a ‘one-crop’ colonial economic policy, common to so many parts of the Empire. The sea lords stopped having their ships mended in the Mediterranean, and the economy, not being based on anything else, went to pieces almost overnight. How much more generous, and how wise it might have been for the home Government to have developed an alternative—some kind of engineering, perhaps. Colonial government, however, is not generally blessed with either generosity or wisdom, and never with foresight.)