Outposts (18 page)

One day I flew with my schoolfriend to the Falkland Islands. He was the pilot of a Hercules carrying several tons of freight and fifty Fusiliers down to Stanley. We rose at three—it was still hot, and a warm wind stirred the ash beside the roads—and had breakfast in a

tent by the runway. There were innumerable briefings, weather checks, radio messages, orders. At five, while it was still dark, we clambered up into the aircraft.

Two Victor jet bombers, old-fashioned, strangely shaped monsters, zoomed into the air a few moments later; and when they were safely airborne we lumbered off and into the twinkling dawn. The bombers were the first of our refuelling tankers. They met us out in mid-ocean, after we had been going for three hours. One fuelled us, the other fuelled him, and both then turned away for home. Six hours further south, when we were well down in the latitudes, and the sea below was covered by low storm clouds, the bombers met us again—three of them this time, one for us, one for him, and the third to top up the second. Then they wheeled away and back up to their cinder-topped base, and we trundled wearily on to Stanley. It took nearly fourteen miserable hours to get us and our cargo from Ascension to the Falkland Islands; five refuelling tankers had been needed, and a small army of logistics men and planners; and had the British not been able to use Ascension the operation would not have been possible at all. I was not entirely convinced the effort on this occasion had been entirely worthwhile: one of the objects we were carrying was a fan for the desk of an army officer—a man who might have thought he was being sent out to deal with an insurrection in the Sudan, but was in fact stationed in one of the coolest, and windiest, parts of the Empire ever known.

Since the Falklands War the island has become furiously busy. Planes howl in and out every day, at any hour. The mess at the American base serves gigantic meals—steaks, jello, milk, instant potatoes—to pilots and technicians all day and all night. Generators rattle, bored soldiers shine machine-guns, warships slip in and out of harbour, replenishment vessels come and lie at anchor two miles offshore, and let a litter of smaller craft suck hungrily at their nozzles of petrol, or water, or aviation spirit. Up on the volcano-sides radar dishes and strangely shaped aerials whir and nod; and wherever the clinker is nearly flat there are graders and bulldozers levelling it still further to make way for yet more new housing, new headquarters buildings,

new mess centres. There has never been anything like it—except that there is no one who has lived on Ascension long enough to be able to compare the daily rounds of 1984 with those of the time before April 1982, when the colony underwent the greatest sea-change of its short career.

Away from the military operations centres, though, much is unchanged. The cable operators still have an office on Ascension, though they run the world’s conversations through satellites today, and the dozens of men who were needed to maintain the circuits of old and keep each other company have dwindled to a very few. In their place there are the men with the very ordinary names—Mr Dunne, Mr Turner, Mr Evans, Mr Davies, Mr Little—who have a very extraordinary job: they work for what is called the Composite Signals Organisation, a secret British Government organisation that makes it its business to find out what other interesting traffic is passing through the satellites and around the ether, and which may be of some use to the West. Messrs Dunne, Turner, Evans and their scores of colleagues, who maintain a polite but scrupulous guard on everything they say, are electronic spies, and Ascension is full of them. There are American spies too, working for a much bigger organisation called the National Security Agency. But while the existence of the British CSO staff is officially acknowledged, the American technicians are not admitted to being on the island, not by anyone.

I toured around the island by helicopter one day—buzzing the lush slopes of Green Mountain, the satellite station on Donkey Plain, the tracking station on the Devil’s Ashpit, the strange volcanic rings of the Devil’s Riding School. We arrived above a cluster of white aerials on the eastern side of the island, near a cliff called Hummock Point. I pointed down, and asked the pilot what they were—and he started, and whirled his craft away, and we roared back to the north of Ascension, leaving the aerials to their secrets. It is said—but then it is always said—that there are vast underground bunkers, crammed with electronic code-breaking machines, and staffed by pale-skinned troglodytes who rarely surface into the sun. All that can be said with certainty is that Ascension is an important little island, and that it derives its importance for more than being a

convenient staging post, halfway between the training grounds of Salisbury Plain and the fighting grounds of East Falkland. It is manifestly not an island that Britain—or America, for that matter—would abandon without a struggle. Happily no one—least of all the island population, which comes on short-term and highly lucrative contracts—wants Ascension to break away from the motherland. (Some of the more radical St Helenians, however, wonder why Britain cannot persuade the Americans to pay rent for their bases on Ascension, and thus help the crippled St Helena economy. Britain refuses even to discuss the matter.)

But HMS

Ascension

is not all warship. It is a floating radio programme, too. On the northern tip, beside one of the few bays that is protected from the man-eating sharks that roam the coastal waters, is a smart white office building with a tall white warehouse next door. This is the Atlantic Relay Station of the BBC; the office teems with administrators, the warehouse with transmitters, and the men sent out to keep them running. There are six short-wave transmitters which broadcast the World Service and the various foreign languages of the oceanside countries (Spanish and Portuguese for Latin America, Hausa, French and Swahili for Africa). I had expected the transmitters to be compact, rather unimpressive machines, all solid-state and disc-driven; instead there were six monstrous grey cabinets, which looked like refugees from a Victorian power station, and which opened to reveal a mass of hot, humming valveware, with long and curiously shaped horns that snap in and out depending upon which frequency band the Corporation wishes to use for transmissions that day. Some of the valves are two feet tall, weigh a hundred kilogrammes, cost thousands of pounds each and put out showers of vivid blue sparks and flames while they are busying themselves with getting the

News in Swahili

to the far side of Africa, or sending

Calling the Falklands

to the sister colony halfway down the same cold ocean.

The last time I arrived in Ascension I came by boat. A school of dolphins had joined us two hours before, and had played joyously under the bows as we ploughed ponderously towards the small

speck of Imperial volcano. We dropped anchor in eight fathoms, a mile off the Georgetown jetty; for fully five minutes I stood enthralled at this strange sight—this mass of reddish-brown rock, rising abruptly from the ocean, its peaks festooned with delicate filigrees of radio masts, with globes and radar dishes and odder, inexplicable devices for talking and listening to the outer reaches of the cosmos. The additions had made the island look unreal, as though it were an outlandishly shaped submarine that had briefly come to the surface to take on air, and would soon sink into the depths once more and sidle off on some mysterious mission.

But I went ashore—nearly drowning myself as I leapt for the rope at the bottom of the Tartar Steps, missed, and slipped on the slime—and took a car to the Residency, up on the slopes of Green Mountain. (It was not always so easy. The wife of a resident naval officer once arrived at the same jetty and haughtily demanded of a rating where on earth Government House might be, and where was the carriage she had expected would be awaiting her pleasure. ‘There’s the captain’s cottage, ma’am,’ returned the sailor, ‘and this here is the island cart.’)

The Residency here was once the Mountain Hospital, for as soon as Napoleon had died Ascension was turned into a huge sanatorium, dotted with hospitals and sick bays where men of the West Africa Squadron could be taken if they fell sick while on anti-slaving duties off the Guinea Coast. It was used as a coaling station, too—yellow-fever and coal being the principal colonial ‘industries’ until the cables came at the end of the century. To get to the Residency involves a long climb—I went past One Boat, past Two Boats, past a water tank called ‘God-Be-Thanked’ and up a helter-skelter of ramps and slopes and hairpins more fearsome than any this side of the Alps.

It would be idle to pretend that the man who fetches up as tenant of the Residency, Ascension, is likely to be a figure on the cutting edge of British diplomacy. It was always one of the least favoured posts in the remit of the Colonial Office, and remains as unpopular today. The Administrator himself has very little to do. He looks after the police force, sets the weekly exchange rate for the St Helena

pound, and issues instructions about road closures and sittings of the magistrate’s court. Meanwhile the civil administration of the island is now actually carried out by the BBC; the Royal Air Force and the various American agencies run the military side.

But assuming he is able to cast off his memories of ambition, the Ascension Administrator can savour a place of unusual loveliness. His house is more beautifully sited than any other in the remaining Empire: its gardens sweep down to cliffs from which most of the island can be seen, and the ocean stretches to the horizon on every side. At night the sky is ablaze with stars, and the island below pricked with the golden oases of light among the black volcanic shadows. There are wonderful vegetables and exotic fruits; and up here, on the high slopes, the weather is pleasant all the year round.

I walked up from the Residency one afternoon, through the groves of trees the sailors and the cable men had brought—eucalyptus, juniper, monkey-puzzle, acacia, Port Jackson willows. Then, as the road wound higher, so the hedges became as tall and as fragrant as any in Devon in summertime. The old farm, with its stables and milking halls and clock tower (where the naval rum was issued), came into view—a granite testament to the amazing energies of the Victorian sailors and marines. The very thought of building a Sussex farmhouse, with a clock, 2,000 feet up the side of a volcano in the middle of the equatorial Atlantic!

Up here was a world quite different from the harsh clinker desert below, where there was no grass, and just a wretched collection of beasts that included spitting wild cats, land crabs, goats and donkeys, and massive Brazilian turtles clambering wearily on to the blazing beaches to lay eggs. Up here there were palm groves and banana clumps, gardens with raspberries and ginger, and fields of grass and gorse. The trade winds, cool at this altitude, swept in across meadows where dairy cattle (administered by an official of the BBC in London, no less!) grazed contentedly. I climbed a stile, and headed on upwards into bamboo forest, where it was dark and cool, and the path was thick and slippery with clean brown mud. I took off my shoes and socks, and waded ever upwards, to the summit of Green Mountain.

At the top, in the tiny old crater, was the dew pond—made by the Navy to catch water, stocked by the Navy to be beautiful. There were blue lilies in flower the day I was there and large goldfish swam lazily through the dappled waters. The remains of an old anchor-chain lay beside the pond, and I had read somewhere that it was the custom to hold it, close your eyes, and wish…

At the far end of the pool, on the topmost point of the island, 2,817 feet above the sea, was a wooden box, with a visitors’ book inside, and I signed it: the last climber had been a wing commander, from Northumberland. Most, indeed, had been military men: two years before the entries were by young soldiers trying to keep themselves fit for war; now they were officers, curious, and with time on their hands. They had come striding up stick in hand, pipe clenched between teeth; in 1982 the men had come running and puffing, with a drill sergeant in hot pursuit, and no doubt they hated the summit, and cursed the slime and the knife-edges of the bamboo leaves, and the crazy accidents of creation that put such ghastly hills out here in the tranquil flatness of the sea.

But this afternoon no one else was in sight. I had Green Mountain all to myself. The only sound was the sighing of the trade winds through the bamboos, and the occasional quiet chatter of canaries down in the meadows. Truly, I found myself thinking, of all the forgotten corners of the Empire this was both the most lovely, and the most strange. Below me was all the machinery and technology of war, and the encrypted chatter of half the world’s spymasters. Down there—and I could glimpse the wastes of lava, and catch the glint of a radar dome—was that hell with the fire put out; up here, where the sailors of Admiral Fisher’s grand Imperial Navy had built a farm and a water supply, and had planted some trees, was something close to heaven. This, these few forgotten acres of hillside, showed to me what the Empire really could be when it tried—Rosebery’s great and secular force for good, which left memorials behind of which everyone could be proud, and for which everyone could be thankful.

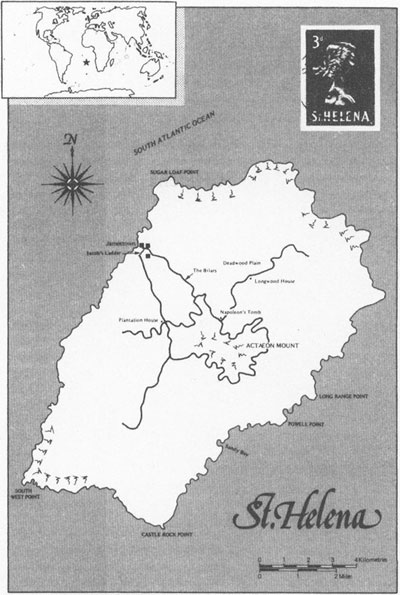

St Helena