Outposts (22 page)

Every nut and bolt of the Imperial machine remains in St Helena, preserved in the amber of her isolation. There is a colonial policeman, in charge of a police force known as the Toys. The last chief came from Birmingham, and by marrying a local girl quite scandalised the island Establishment (though the Attorney-General did the same, and promptly took the stunningly pretty Saint off to a new posting on the Caribbean island of Anguilla). One advantage of the chief’s marriage is that he became wholly accepted by the island community, to the point of being given a nickname. Islanders take nicknames quite seriously: there was a Conger Kidneys, a Cheese, a Fishcake, a Biffer and a Bumper. The police chief, for reasons perhaps better known to his wife, was called Pink Balls.

There is a fully-fledged bishop, too, and a cathedral that was prefabricated in England and brought out to the island on a ship.

The bishop presides over the smallest diocese in the Anglican communion (though the largest in area—it extends all the way up to Ascension Island, and while only having 7,000 souls, looks after an almighty stretch of ocean). He and his priests, who are recruited in England for thirty-month contracts, seem not the slightest bit reluctant to marry off young islanders who quite cheerfully bring a baby or two along to the wedding ceremony. Half the children born on the island are, technically, illegitimate. The islanders who dote upon all children call them ‘spares’, and if they are old enough to take part in the bacchanal that usually follows an island wedding, are welcomed like old and much-favoured relatives. Since the ceremony legitimises them they, too, have something to celebrate.

Both police and church worry about the growing crime rate. Some blame the fact that many islanders now work on Ascension, and come back full of American ideas (many of the jobs on the dependency being for the US Navy, or NASA, or PanAm). Some say video cassette recorders, of which there are a number on the island, bring evil in their train. Whatever the cause, there has been a dismal increase in misbehaviour. There have been three murders since 1980 (the previous killing was eighty years before; in some intervening years so little crime was committed that the magistrates were presented with white silk gloves as a token of island innocence). Murder trials, almost without precedent in living memory, are major events: a judge has to come from Gibraltar, defence lawyers must be brought out from England, and on conviction the prisoner must be taken to Parkhurst to serve his time—the island prison being too small and insecure. The St Helena Governor petitions the Home Office in London under the terms of the Colonial Prisoners (Removal) Act.

All the institutions that provide a link with ‘home’ are lovingly nurtured. There are Boy Scouts (the 1st Jamestown Troop, shorts still worn, and socks with flashes) and their Guides, an Armistice Day parade, an Agricultural Show, a St Helena Band and a specially composed St Helena march. And there is cricket, played on the only piece of level ground on the island, about the size of a postage stamp (one of the island’s only ways of making money is through

the sale of stamps) and with deep ravines on all four sides. (They say that if they could find another piece of level ground they would build an airfield, which might solve the island’s problems overnight.) The ravines have caused problems in the past: during one match a fielder, running backwards for a high ball, fell off the edge and was killed. The scorecard, as laconically as befits the sport, recorded his passing by writing ‘

Retired, Dead

’. The Governor of the day built a fence along the boundary, and a ball that falls down the cliff scores six.

And along with the trappings of Empire, so also a real affection for its leaders. It is rare to find a house in St Helena, no matter how humble a shack, without its picture of the Queen, or the Queen Mother, or Princess Diana and Prince Charles, pinned over the mantel. Sometimes it is an official portrait, bought from Solomon’s store; more usually it is a gravure print torn carefully from the likes of

Woman’s Own

. Once I called at a small house on Piccolo Hill and asked the woman, in passing, if she had a portrait. She reddened, and looked briefly terror-struck. ‘I’m terrible sorry but I’ve not,’ she stammered. ‘I had no idea they’d be sending anybody up to check.’ It took some time to convince her I was not from the Castle, testing the loyalty of Her Majesty’s most distant subjects.

In every apparent way, then, St Helena is, or seems to be, British. The people, from whatever ethnic origin, all sound like friends of Sam Weller; they have their own version of the BBC relayed down to them each day; they get the

Telegraph

and the

Observer

at the local library; there are still Humbers and Veloxes and Minis parked on the streets; people eat marmalade, and fishcakes, and stop in mid-afternoon for tea.

But there are two signal differences between the citizenry of St Helena and Her Majesty’s subjects back home in Britain.

The Saints, first, are poor. There is no work for them, barring a few jobs in the vestigial fishing industry (an industry which by rights should take off—the island is surrounded by rich fishing grounds, and one day I sat next to a man with a bamboo pole and a hook and who pulled tunny out of the sea at the rate of one every two

seconds). Almost all capable males, aside from those who go to Ascension, or crew ships away at sea, are employed by the Government—digging holes and filling them in again, in effect.

London complains that its aid to the island amounts to about a thousand pounds per head—more than to anywhere else on earth (except the Falkland Islands since the 1982 war). But in effect most of that money is paid out in wages—and, by British standards, derisory wages they are, too. I spent some time with a man who lived in a tiny cottage overlooking Sandy Bay. His family of ten and his eight cats lived with him. He worked as a labourer for the Public Works Department, and was paid twenty-six pounds a week—‘hardly enough’ he admitted. The nearest shop was five miles away, and sometimes one of his daughters walked the entire way barefoot. Living, he said, was ‘very hard’.

And yet he was loyal, did have a picture of Prince Charles hanging in the living room, thought the Falklands War was an excellent thing and was sorry not to have gone himself. He would have done anything to fight for Her Majesty, to show how British and loyal he was. The only thing was…

And then he raised the second point—a point which came up again and again during my stay. Why—just why—were the islanders not counted as Britons by the Government back home? The Falklanders and the Gibraltarians were: why not the Saints? ‘These are not primitive tribesmen or coolies,’ as the South African, Lawrence Green, put it two decades ago. ‘These are a unique and truly multi-racial community of considerable natural intelligence and loyalty…’ So why does Britain not take them in—more precisely, why, by the passage of the British Nationality Act, did Britain seek to exclude them from the privileges of Britishness, and yet still rule them?

After all, islanders would keep mentioning to me—the Charter was our guarantee. The Charter promised we would have rights.

I first learned about the famous Charter—famous, that is, to every St Helenian—one sunny afternoon, when I was strolling up Napoleon Street in Jamestown. I was passing a little café, where motherly waitresses bring tea and buns each afternoon (and

barracuda fishcakes for supper), and where the customers are slow old ladies in enormous summery hats who look like refugees from a Women’s Institute in England, only rather more tanned. One lady stepped out of the shadows as I passed and, with a quick look up and down the street to make sure no one was watching, thrust an envelope into my hand.

Inside was a letter, and a leatherette-covered diary for the year half gone, with more writing inside, and a five-pound note. It asked me to send a copy of my researches to a Saint who now lived in Yorkshire, and to make sure that ‘the sad matter of our Nationality is raised back in London. The Charter says we are British, and can come to Britain any time we want. But we can’t. The Government won’t let us. They won’t admit we are full citizens. It is very unjust. We were colonised by British people, from Britain. And now they turn us away. We want to know why?’

The document, preserved in the Castle, is written in the name of King Charles II. It is very long. The section that most Saints know by heart—or have since the Nationality Act was passed in London—runs as follows:

Wee do for us, our heirs and successors declare…that all and every the persons being our subjects which do or shall inhabit within the said port or island, and every their children and posterity which shall happen to be borne within the presincts thereof shall have and enjoy all liberties, franchises, immunities, capacities and abilities, of franchises and natural subjects within any of our dominions, to all intents and purposes as if they had been abiding and borne within this our realms of England or in any of our dominions…

In other words, the Saints are, by ancient right, as British as had they been born in Sevenoaks, or Knotty Ash. So why have they had their privileges stripped from them? And will they get them back?

A long and energetic campaign has been mounted on their behalf. (The island’s Anglican synod sent a telegram to Downing Street, which raised some eyebrows.) Calculations were made showing that even if they were handed proper British passports, and not the

half-worthless ersatz papers they have today, only about 800 would ever come to settle in Britain. ‘Hardly a flood,’ said one islander. ‘You’ve nothing to be afear’d of.’

But the Government seems in no mood to budge. There was a debate in the House of Lords late in 1984, at which friends of the island, men such as Lord Buxton and Lord Cledwyn (who went there in 1958, returned home shocked at the poverty and neglect, and wrote an article in the

Daily Mirror

entitled ‘Paradise on the Dole’), spoke with passion and eloquence about the sad fate of this most enchanting island. But Lady Young, representing the polite but unyielding face of Mrs Thatcher’s immigration policy, said she had no plans to change the law. Of Britain’s remaining colonies only the Falklands and Gibraltar enjoyed the privilege of total national equality; the remainder—Hong Kong, in particular, which promises millions of Cantonese at Heathrow should the strictures be relaxed—are, to all intents and purposes, peopled by aliens. (Unkinder critics noted that the Falkland Islanders and the Gibraltarians enjoy one other unique quality within the Empire—a quality which may or may not have been wholly unconnected with the decision to reserve the privilege of full British nationality to them. They are white. The Foreign Office regards such suggestions as unworthy.)

So—a ‘ridiculous dwarf of a Colony’ a ‘Cinderella’ ‘Paradise on the Dole’ ‘Distress on St Helena’ ‘Bleak Outlook—Colonial Office largely responsible’ ‘Hard Times on Forgotten Isle’ ‘Famous Island the World has forgotten’. These were all headlines from the Forties and Fifties. And there were smaller, more human tragedies—like the story of the island’s only leper, who lived alone on Rupert’s Bay, and who was sent a second-hand gramophone by a well-meaning lady in Eastbourne. The Government charged him threepence duty on every single record.

Or the time there was a bus crash on Christmas Eve, and ten islanders were hurt. The Governor found he couldn’t alert anyone in the Foreign Office for seven days, and it took the best part of a month before a doctor came out. The only recorded remark from

an island Colonial Service man was that he was sorry for some friends of his, because the crash had meant they had lost a good cook. Delays in answering telegrams are still considerable; John Massingham, a recent Governor, complained publicly of the second-rate clerks who manned the island ‘desk’ in London, and said it often took months, and several reminders, before a simple request would be answered, or even acknowledged.

Successive British Governments, in short, have little to be proud of in their running of this lovely place. Poor decisions, ignorance, insouciance, obstruction and unkindness have characterised British rule in the past. It seems so unfair a lot for so good-hearted and so loyal a people.

The memory of them that will remain with me for a long, long while is of a Sunday morning at the Sandy Bay Baptist Church, a tiny stone chapel perched on a bluff overlooking the ocean. Twelve people had toiled up the hills to Matins, and the old minister, his ancient and threadbare suit buttoned, his shoes lovingly polished, was leading them in song. There was no organ, nor a piano. Just thirteen devout old islanders, dogged, perspiring in the summer heat. Their thin voices rose out into the valley. ‘Lead us, Heavenly Father, lead us…’ they sang.

It might have been Devon, or Cumberland, or Suffolk, on a summer Sunday morning. When the service was over the people shook the minister’s hand and then, in small family groups, straggled off down the hillside, and back for a Sunday lunch of tuna and rice, blackberry duff and island-brewed beer.

Life continues to a noble and unmistakably British routine on St Helena. It has for 300 years. It probably will for many more, though times will get harder, the suits will get a little shabbier, lunches will get more frugal still. As it was for Napoleon, so this island has become a rock of exile for a British way of life—a way of life now only to be found in Britain in isolated rural retreats.

Unwittingly the St Helenians have preserved it and, come what may, they seem determined to preserve it for a long while still to come. Five thousand miles from their imagined home the Saints, forgotten and forlorn, go marching on.

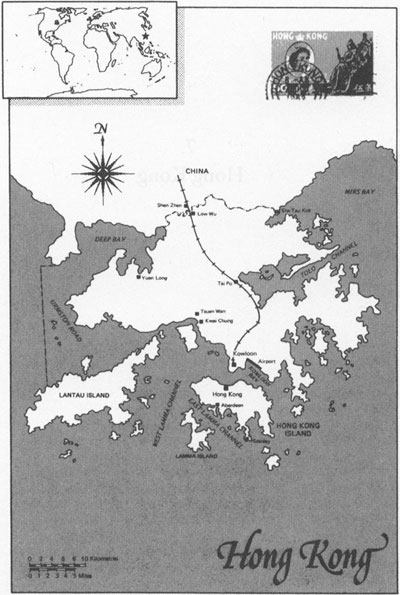

Hong Kong