Oxfordshire Folktales (17 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

On the first Monday in July local farmers in the district, who, through being born and bred in the neighbourhood, have mowing rights in the meadows, assemble to draw the lots. They used to do this down on the meadow, but these days it transpires at the Grapes Inn – maybe too many wettings or not enough! The Head Meadsman arranges for the drawing of the Balls and for the cutting of the hay. He needs to be a sharp ‘un for its a mighty fierce doings, measuring out the various lots. I’ll try my best to describe it to you, so listen close.

The meadows were divided into strips known as customary acres – or as much as a man may mow in a day. Locally, this was called ‘one man’s mowth’. These strips were divided between the thirteen farmers whose names appeared on the original Balls. Then as the farms disappeared, and only eight remained in the village, the strips were absorbed by them. Consequently, some farmers had more hay than they required and so sold the surplus before the actual mowing day arrived and, when the Balls were drawn, the purchasers claimed the strips they had bought.

Following it so far?

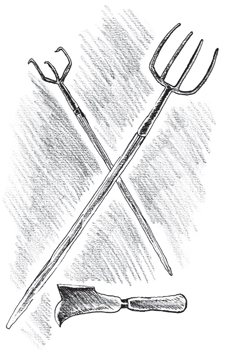

Solemn as pallbearers, the two head meadsmen would then proceed to a certain spot in the meadow about to be mown – they would walk a stately pace, but that might have been just the cider. A Ball would be drawn from the bag, and its name loudly proclaimed. A man with a scythe would cut about six foot of hay in a few sweeps, and another man quickly cut out the initials of the claimant in the ground. Then they would all proceed to the next lot and a Ball would be drawn again and another man’s initials inscribed amid the freshly mown hay. This continued until all the lots were marked and, all the while, another meadsman would carefully note down the details of each strip and its owner to avoid dispute later on. In order to distinguish the boundary between the strips, a number of men would tread up and down them – this was called running the treads.

The meadows had lovely names: Oxhay, Picksey (now Pixy), Little Hayday, Great Hayday, Big Couch, Little Couch, The Hope Yard, The Ship and West Mead. They lie on the north bank of Old Father Thames – one hundred and seventeen acres I’m told. Eight of these were tithed to vicars and the scholars of Exeter College, and they were known as Tithals or Tidals.

There, you keep listening and you’ll keep learning!

In order to cut the meadows in one day, which was no mean feat, about one hundred labourers were imported into the village. Large quantities of liquor were kept close by, and in the hedges – so that the thirsty men could stop frequently, quench their thirst, and carry on with renewed vigour. On the completion of the mowing, they were very merry indeed and the races, which always wound up the proceedings, were often run by many pairs of unsteady legs. The main race was for the honour of securing a garland, which the winner placed in the church, there to remain for one year.

Yet when men and drink mix, things soon turn foolish. The fair got rowdier and rowdier. Once, there were riots and a man was killed. That was a terrible day. The vicar preached fire and brimstone at us the following Sunday.

After that they spread the mowing over three days – to water it down, so to speak – and things became more civil.

I imagine a few of them rioters ended up at Stock Trees. Three mighty trees once grew there, by the village stocks. I remember them poor lads getting a proper pelting, and perhaps I joined in too. Garden refuse and rotten fruit, cowpats, the lot! Then they were marched across the road by old Farmer, the village constable with his black baton, to spend a night in the lock-up, a guest of the magistrate. That soon sobered ‘em up!

Well, the wheel turns and village life gets back to normal pretty sharpish after the Fair days. Work to be done. The Mead Balls are put away ‘til the following year.

We don’t let the grass grow under our feet around here!

What? You cheeky so-and-so! Off with you, before I cuff you round the lobes. I’m not too old to cut you down to size. I’m a Yarnton girl. We know how to swing scythes round here.

![]()

Although the tradition at Yarnton has become a low-key affair, mowing fairs still take place in some parts of the country, such as the Somerset Scythe Fair – where one can get a flavour of times past. A mowing match is held there every summer. I have imagined the Mowing Fair at Yarnton from the point of view of one of the old villagers, based upon an account I read:

Grandmothers’ Tales,

a story by Joan Roe published around 1981 about Yarnton life. There is a curious footnote to all of this.

Yarnton was known for many years as the grave of the mammoths. Records exist telling of enormous animals such as wild oxen, large deer and hippopotami, which roamed the district seeking water. It was at a time when the whole country was drying up, and eventually the only water left for them was in Portmeadow. There they assembled, a vast army of huge animals, awaiting their last drink. Such masses of bones and phosphate of lime has been found that geologists say the animals lay in heaps, and all died practically at the same time. And from the bones of dragons grows the good green grass of Yarnton meadow.

T

HE

O

TMOOR

U

PRISING

I remember my father telling me all about it, as clear as yesterday. Did he take part in those September riots at St Giles Fair? So he did. Buy me a pint of Flowers and I’ll tell you the long and the short of it…

It all started with a young upstart called Coke. Lord so-and-so stoked the fires alright. He wrote a scandalous pamphlet called … let me get this right: ‘A short view of the Possibility and Advantages of draining, dividing and enclosing Otmoor.’ Wicked it was. Why? Because it would drive us off our land and take away our commoners’ rights, to gather and graze fuel for hearth, fodder for cattle – that’s why! Otmoor might not look much to the outsider; some call it a marshy wasteland! Can ‘ee imagine? Well, perhaps you can, but on a summer day there’s nowhere more lovely on God’s good Earth. We’d drive our herds out there to pasture on the open plain; us littl’ uns would tend the flocks of geese which loved to peck on the roughage; old nans scraped up the cow dung to sell for a few pennies; ducklings splashed in the pools; fish leapt in the streams, and, standing tall round it, the seven towns of Otmoor: Charlton, Oddington, Beckley, Noke, Horton, Fencott and Murcott. Like a kingdom unto itself. How could they take that away? Not without a fight, that’s for sure…

And, by thunder, they got ’un!

We tore down Coke’s notices wherever we saw ‘em – made good kindling. Yet the young fool persisted. High and mighty, he would sound off so: ‘To let four thousand acres of good land lie barren and desolate for about a dozen old women to pick up a scanty livelihood from cow dung and goslings is too great an absurdity to be supported.’ But supported it was – we got ourselves an ally in the form of Lord Abingdon no less, God bless him, who championed our corner. He stopped Coke’s plan in court good and proper.

But the fool’s plans would not go away – even when Coke did, to Nova Scotia. Had enough of us mardy Otmoors! When we get a feeling in our water, we’re like the Moor-Evil – gets right into your bones on a claggy day. Nothing can shift ’un. And nothing can shift us!

It took ‘em fourteen years to get started. The results of their folly was plain to see straight away – by playing with the drainage they’d flooded the farmers’ fields. My, they weren’t happy, I can tell ‘ee! They went in the dark and threw down them embankments! Released the waters from the dykes. As soon as a fence was put up it was thrown down again. There was that young hotspur Price, whipping the men up with his fighting talk, here at The Crown – used to be Higgs’ Beerhouse back then. Josiah Jones, an outsider, came to stir up trouble even more. And even a gentleman, Richard Smith, placed an appeal in the newspaper, which ruffled a few feathers.

It wasn’t long before there was a crowd of some say a thousand – men, women, and children – walking out onto the moor together in protest. What a sight it was! The whole moor was covered with people tearing down fences; pulling up hedges; un-enclosing the land. That was the summer of 1830. Everyone round here remembers it. Harvest time. Back then, you could hear the scythes singing through the fields – the whole village would put their backs into it. And here we were, gathering in a different harvest. Yeomanry arrived and arrested forty odd, carting them off to Oxford Castle. But it just happened to be St Giles’ Fair – first Monday in September, the way it has been for centuries. There, the crowds had been fired up by the likes of Price and Jones and were ready for a fight. They chanted ‘Otmoor forever!’ again and again. Sticks and stones started flying left, right and centre. The Guard struggled to frogmarch their prisoners through the press to the castle. They were kicked and punched by men and women alike – my father and me amongst them. It seemed like a great game to me. A carnival. By the time they reached Beaumont Street the Yeoman were in a sorry state and all their prisoners had slipped the collar. Victory to the people!

How we sang and danced that night – drunk on success!

But we celebrated too soon. We had won the battle, but not the war. They kept rebuilding the fences, planting the hedges, raising the banks, and, stubborn as mules, we kept pulling ‘em down! We got ourselves organised – under the cover of darkness and in disguise small teams would go off ‘on business’. I’d never forget the times my father would come back with his face blacked up like a mummer or, once, even dressed as a woman! They were handy, those night-raiders – once they tumbled a stone bridge!

The magistrates tried to recruit Parish constables to help patrol the moors, but no local would risk swearing in if he knew what was good for him. One of the constabulary was even on our side. A few backhanders here, a few pints there and it was ‘business as usual’.

But that all changed when they brought in Layard of the Law – that’s what they called him, though we called him something else – who whipped his team of fourteen into shape. It was hard to get away with the night-raids then. Nobody wanted to end up in gaol; or, worse, losing the roof over your head, what with mouths to feed and all. But there were concerns about the cost of this special constabulary defending what was, in effect, a private property speculation. The numbers were dropped to four and our raids began again in earnest – until the numbers were raised again. And so on. Right old game of cat and mouse it were!

This lasted for four years. But by 1835 the county no longer had a police force, for the rioting had ceased. The farmers had been talked round – they had their own property and land and livelihoods to worry about and couldn’t risk losing it by being involved in anything illegal, like. Folk burn out, move on, or simply get old. Bones begin to ache until it’s not so much fun, running around on a dark moor, in the mud and mist.

And so the protests died away. The moors were finally enclosed – Coke’s fool-plan finally came true, twenty years on, but it never brought profit to the landowners, so, in a way, we were vindicated. The common folk had the common sense all along.

And to this day, the Otmoor uprising is remembered round these parts as an example of what folk can do when they work together and stand up to the foolish powers who are meant to rule us: ‘Otmoor Forever!’

![]()