Oxfordshire Folktales (18 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

This historical story seems more pertinent than ever. I wrote it in the ‘Year of Protest’, 2011, when the Occupy movement was in full swing. To this the day in the area, the Otmoor Uprising is remembered with local pride in such places as The Crown Inn in Charlton-on-Otmoor – this was formerly Higgs’ Beerhouse, the focal point of the rebellion. Here, on the 6th of September 1830, the locals organised their revolt, no doubt fuelled by the local brew and stirred up by the likes of Bartholomew Steer, a local carpenter who preached ‘the politics of Cockayne’, according to scornful accounts in the press. Then, as now, the press was used as a political weapon, but nothing could stem the tide of revolt. Never underestimate the power of the people!

![]()

T

HE

R

OOFS

OF

B

URFORD

The charmingly picturesque town of Burford – one of the gems of the Cotswolds – seems to be the quintessence of genteel middle England. Nothing seems to be out of place and one can imagine the status quo being maintained this way for decades; a pleasant, comfortable sleepiness. And yet the town has some dark stories in its history, revealing a different character to the town. Here are a couple.

* * *

Laurence Tanfield was born in the town in relatively poor circumstances, but through his own efforts and good fortune rose to the heights of society there. However, his story shows that success should not be gained at any cost and one should never forget one’s roots.

His mother managed to get him educated for the Law; his own drive, industry and covetousness advanced him in wealth and dignity. He became sergeant-at-law; a judge; and, finally, Lord Chief Baron.

With his hard-earned wealth, Tanfield purchased and rebuilt Burford Priory, and in 1617 he bought the lordship of the manor and became first resident lord of the manor since the Norman Conquest. How far he had come from his lowly birth! One would think such a reversal of fortune would make a man count his blessings and remember those who helped him on his way. Instead, the wealth and power seems to have turned Tanfield into a cruel-hearted tyrant.

The good citizens of Burford had come to regard their town as a Royal Borough – with its own privileges and rights – they were soon to learn how fickle Fortuna is. In 1620, a

quo warranto

was brought against the Burgesses of Burford by the Attorney-General and they were tried in a court presided over by Sir Laurence Tanfield. By its ruling, the Burgesses were stripped of their ancient rights.

Overnight, Tanfield made himself the most unpopular figure in town.

Hard-nosed as Tanfield was, harder still was his wife, Lady Tanfield. She was infamous for her dislike of the citizens of Burford, saying how she would like to grind them to powder beneath her chariot wheels. In a strange way, her wish came true.

The impact of the Lord Chief Baron’s harsh ruling rippled out to the surrounding towns and villagers, so that the Tanfields were equally despised in Great Tew, Whittington and Wilcote. It was a great relief to the area when the Tanfields shuffled off this mortal coil. But if their wish was to rest in peace, it was not granted.

Lord Tanfield was sometimes seen haunting the backroads of Whittington in his spectral coach – the area became known as ‘Wicked Lord’s Lane’. It boded ill for whoever saw the coach.

And as for Lady Tanfield, she survived her husband by a few years – clinging onto life with the grim stubbornness with which she had coveted her wealth; but finally, she gave up the ghost. Yet even then, her spirit did not find rest. She was said to haunt the town, riding over the distinctive roofs of Burford in a fiery chariot, sometimes with Sir Laurence, foretelling any misfortune likely to overtake the town – like Hayley’s Comet heralding the Norman Conquest.

In the eighteenth century, she became so troublesome that a band of seven clergymen came together to ‘lay’ her troublesome spirit to rest. They succeeded in calling her into church and conjuring her spirit into a bottle – which they corked securely before throwing it into the river, under the first arch. It was believed in times of drought, if the river level sank too low, and the arch ran dry, Lady Tanfield would rise again and once more ride over the roofs of Burford. One summer it was dry for so long, that the river began to ‘hiss and bubble’. The citizens of Burford grew so concerned that they formed a human chain and poured pail after pail of water in from upriver, until, finally, the level started to rise, and the fiery spirit of Lady Burford was cooled once more, saving the town from the infuriating clattering of her chariot.

![]()

This tale bears a passing resemblance to that of ‘Squire Crowdy of Highworth’ – as related by Kirsty Hartsiotis in

Wiltshire Folk Tales

(The History Press, 2011). It seems Burford isn’t the only village that has been forced to exorcise troublesome gentry!

OUGH

M

USIC

Another tale of Burford is far more down-to-earth, yet is another cautionary tale of marital hell…

Back in the day, legal divorce was costly and out of the range of poor folk – but there was another kind of separation involving the rough justice of the streets. It was commonly believed that a man, wishing to dispose of his wife for whatever reason, could put a halter around her neck and offer her for sale in the market place. This was sometimes a mutual arrangement agreeable to all parties, sealed with a drink in the local tavern and a couple of witnesses. But sometimes things weren’t so amicable, and the husband would sell his wife to a stranger.

In 1855, a Burford man sold his wife at Chipping Norton market for the handsome sum of twenty-five pounds – half a crown was the usual going rate for a ‘broken in’ wife!

The cold-hearted husband lived in Simon Wisdom’s Cottages at the bottom of town – down by the bridge. By this time, the town no longer considered this a civilised way to treat one’s spouse and so, when word got out of this ‘market-place divorce’, for three nights running a crowd gathered down by his cottage and made ‘rough music’ with horns, trumpets, tin whistles and cans beaten with sticks. On the third night they burnt a straw effigy of the man outside his door. This was too much for the inhabitant and he burst out of his house with a pitchfork and thrust the mannequin into the river, and a good many of the crowd too.

Yet, when he had cooled down, the man reflected on his actions. Perhaps he had been too hasty, too harsh. He went back to Chipping Norton and there offered to buy his wife back for fifteen pounds, ten pounds less than he asked for originally: depreciation, of course!

![]()

This was recorded by Katherine Briggs, as related by a Mr Hambridge to his daughter, who, as a young boy, had been a part of the ‘rough musicians’ and had ‘splashed through the river and escaped’. He never mentioned any names, for at the time he related the anecdote, ‘some descendants of the people were still living’.

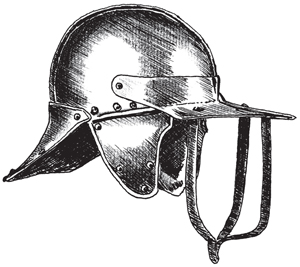

Burford saw even greater turmoil during the Civil War – three hundred and fifty Levellers were captured here as they rested on their way back from a disastrous skirmish with Lord Fairfax’s troops at Salisbury. They were on their way to Banbury, but exhausted by their fight, were forced to rest. Caught sleeping, they surrendered. Four of them were selected for execution. The ringleader capitulated and was pardoned at the eleventh hour. The others were not so lucky: the three Levellers were lined up in front of the church and shot on the 17th of May 1659; the round indentations of the bullet holes can still be seen – a chilling detail in an otherwise charming place.

![]()

T

HE

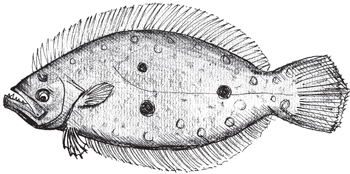

F

ISHERMAN

AND

H

IS

W

IFE