Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris (16 page)

Read Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris Online

Authors: Graham Robb

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France

I

N HIS OFFICIAL OFFICE

above the Seine–not the private study next to his bedroom, but the state room with three large windows looking onto the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville–the model inhabitant of New Paris sits at a large desk. It is, without a shadow of a doubt, a glorious morning. His shoes are spotless; he is breathing easily. No one has arrived late for work. A statistic can be brought to him within minutes. A garden of Mediterranean shrubs and sub-tropical flowers separates his building from the river.

Georges-Eugène Haussmann almost dwarfs his desk, which occupies the centre of the room. When he wears his medals, as he does today, his chest looks like an expensive apartment block. He can imagine–he has seen enough caricatures of Baron Haussmann the demolition man, the trowel-wielding beaver, the monumental henchman of Napoleon III–his forehead supported by caryatids. When the Emperor arrives, he will have to stoop to compensate for the difference in height.

Behind him, mounted on rolling frames, the specially engraved 1:5000 map of Paris (not sold in shops) stands ready to be wheeled into the light. It forms his backdrop when he sits at the desk. He often turns around and becomes absorbed in it. Notre-Dame, which is now exposed and visible across the river, precisely where it ought to be in relation to everything else, is the size of his thumbprint; the rectangle of the Louvre and the Tuileries is contained within the compass of his index finger and his pinkie.

He looks down at the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville and sees the accelerated movement of carriages across the square. He understands the flow of traffic, the vents and flumes of intersections, the multiple valves of his radiating, starry squares, of which there are now twenty-one in Paris.

Thanks to him, parts of Paris have seen the sky for the first time since the city was a swamp. Twenty per cent of the city now consists of roads and open spaces; thirty per cent if one includes the Bois de Boulogne and the Bois de Vincennes. For every square metre of land there are six square metres of floor space. The outer suburbs have been incorporated into the city, which is now fifty per cent larger than it was before 1860.

Recently, he has been asked to redesign Rome. The irony is not lost on him, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the son of Alsatian Protestants. The Archbishop of Paris paid him a compliment that is engraved in his memory and that he would like to see engraved on a plinth:

Your mission supports mine. In broad, straight streets that are bathed in light, people do not behave in the same slovenly fashion as in streets that are narrow, twisted and dark. To bring air, light and water to the pauper’s hovel not only restores physical health, it promotes good housekeeping and cleanliness, and thus improves morality.

It also allows a busy man like Baron Haussmann to reach any part of Paris within the hour and in a presentable condition. It means that he can dovetail his duties as a father and a husband with official functions, and with the performances of Mlle Cellier at the Opéra–the actress he dresses like his daughter–and Marie-Roze at the Opéra-Comique. He has created a city for lovers who also have families and jobs.

He was brought in as a steam-roller, as a man of experience and grit. He knows that a regime founders, not on barricades, but on committee tables. The Emperor would rather not disband the Conseil Municipal, but he would like to see it behave with one mind (his own). Baron Haussmann has no intention of running budgets like a petit bourgeois. The days of cautious, paternalistic Préfets are over. A great city like Paris must be allowed her whims and extravagance. Paris is a courtesan who demands a tribute of millions and a fully coordinated residence: flower-beds, kiosks, litter-bins, advertising columns, street furniture,

chalets de nécessité

. She will not be satisfied with small-scale improvements.

Later that month, his childhood home will be demolished.

He is often asked (though not as often as he would like) how he manages to run the city and to rebuild it at the same time. He tells them what he told his accountants and his engineers when he took over as Préfet de la Seine, thirteen years ago:

There is more time than most people think in twenty-four hours. Many things can be fitted in between six in the morning and midnight when one has an active body, an alert and open mind, an excellent memory, and especially when one needs only a modicum of sleep. Remember, too, that there are also Sundays, of which a year contains fifty-two.

Since he grasped the reins of power in 1853, three Heads of Accounting have died of exhaustion.

He looks down at the square and sees a row of taxi-cabs and a small detachment of cavalry. The Emperor is due to arrive, to view the commissioned photographs. His carriage will encounter a stretch of unrepaired tarmacadam where the Avenue Victoria meets the Rue Saint-Martin, and he will arrive approximately three minutes late.

Seventeen years ago, Louis-Napoléon arrived at the Gare du Nord with a map of Paris in his pocket, on which non-existent avenues were marked in blue, red, yellow and green pencil, according to the degree of urgency. Nearly all of those avenues have now been built or scheduled, and many of the Baron’s own ideas have enhanced the original plan. The Île de la Cité, where twenty thousand people lived like rats, is now an island of administrative buildings with the Morgue at its tip. The waters of the River Dhuys have been brought sixty miles by aqueduct, and Parisians are no longer forced to drink their own filth, pumped from the Seine or filtered through the corpses of their ancestors.

Haussmann told the Emperor about the conversation that took place after the council meeting–because the Emperor likes to hear about his steam-roller getting the better of ministers and civil servants:

‘You should have been a duke by now, Haussmann.’

‘Duke of what?’

‘Oh, I don’t know, Duc de la Dhuys.’

‘In that case,

duc

would not suffice.’‘Is that so? What should it be, then? Prince?…’

‘No, I should have to be made an

aqueduc

, and that title is not to be found in the list of nobiliary titles!’

Some people say that the Emperor never laughs, but he laughed when he heard about the aqueduke.

Anything that binds him to the Emperor is good for Paris. That year, his daughter gave birth to the Emperor’s child, three days before her marriage, to which the Emperor gave his blessing. His Majesty even offered to pay for a dowry, which the Baron refused, because no one must be able to accuse him of corruption.

H

E STANDS WHERE

the mirror shows him in his entirety, from bald head to polished boot. At times like this, when a few extra minutes have been built into the schedule, he allows himself the luxury of remembering. He remembers the boy with the body of a man and an incongruous susceptibility to asthma. He remembers–in this order–his home in the quiet Quartier Beaujon, the boots that stood waiting for him every morning, the walk to lectures in the Latin Quarter, the depressing view that faced him like an insult from the arch of the old Pont Saint-Michel, and the state of his boots after the square where the drains of the Latin Quarter had their muddy confluence.

All that ugliness will vanish from one edition of the map to the next. The Boulevard Saint-Michel has smashed through the warren of streets, and the new Boulevard Saint-André will erase the Place Saint-André-des-Arts. The ends of the buildings exposed by the Boulevard Saint-Michel have been cauterized with a fountain on which a snarling Satan (too small for the Baron’s liking) is trampled by a Saint Michael with wings as beautiful as a waterproof cloak. He calls this his revenge on the past.

1. From the ‘Plan Turgot’, by Louis Bretez (map commissioned by Michel-Étienne Turgot), 1734–39.

2. Louis-Léopold Boilly,

The Galleries of the Palais Royal

(1809; the original version, now lost, was shown at the 1804 Paris Salon). Some of the gentlemen may be British visitors, taking advantage of the Peace of Amiens (1802–03).

3.

View taken from under the Arch of Givry

(1807), by John Claude Nattes, engraved by John Hill: Pont au Change, Conciergerie and Tour de l’Horloge. The arcades, flooded at high tide, ran under the Quai de Gesvres and later formed part of a tunnel in the Métro.

4. ‘Monsieur, someone has robbed me of a thousand-franc note’: Honoré Daumier’s view of Vidocq’s Bureau des Renseignements.

Le Charivari

, 6 November 1836.

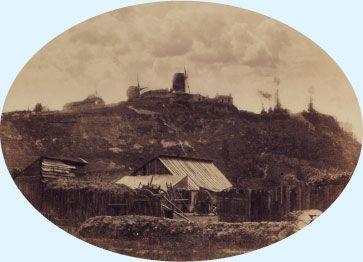

5. Gustave Le Gray,

Paris, View of Montmartre

(a montage: cityscape, c. 1849–50; sky, c. 1855–56).