Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris (17 page)

Read Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris Online

Authors: Graham Robb

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France

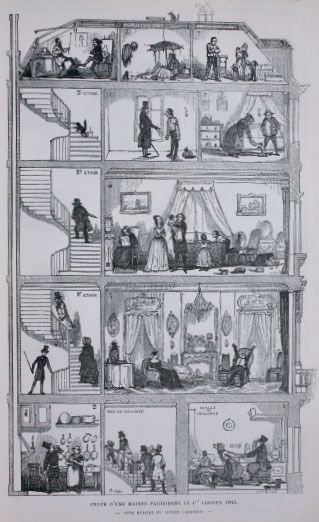

6. ‘Cross-section of a Parisian house on 1 January 1845’, by Bertall (Albert d’Arnoux).

Le Diable à Paris

, vol. II (1846).

7. ‘Le Stryge’ at Notre-Dame (1853), by Charles Nègre. The man is the photographer Henri Le Secq. The streets below were demolished to make way for the new Hôtel-Dieu hospital.

8. The Siege of Paris, 1870, by R. Briant: the Prussian army to the south of Paris, and Thiers’s fortifications, on the line of the present Boulevards des Maréchaux, just inside the Périphérique.

9. The Hôtel de Ville, torched by Communards. June 1871.

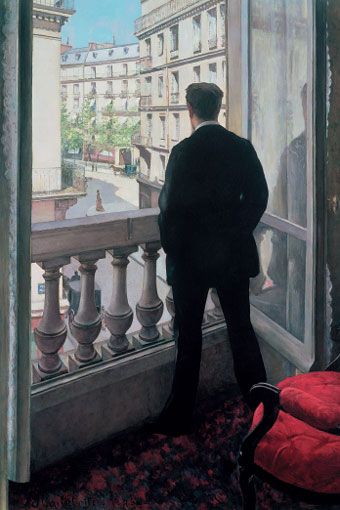

10. Gustave Caillebotte,

Young Man at His Window

(1875): the artist’s brother at the corner of Rue de Miromesnil and Rue de Lisbonne, with Boulevard Malesherbes in the background.

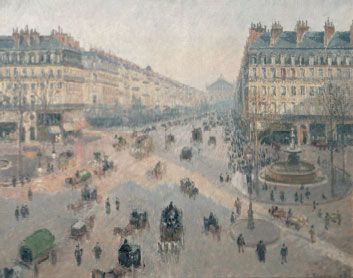

11. Camille Pissarro,

Avenue de l’Opéra, Sun, Winter Morning

(1898), from the Grand Hôtel du Louvre.

12. Universal Exhibition of 1900: Champ de Mars station, Celestial Globe and Maréorama (an attraction simulating a sea voyage from Paris to Yokohama).

When he took the Emperor to see this new gateway to the Latin Quarter, the Emperor looked along the parallel lines of house-fronts, and his eye fell, as planned, on the spire of the Sainte-Chapelle across the river. Then he turned to the Baron and said, with a smile, ‘Now I can see why you were so keen on your symmetrical arrangement. You did it for the view!’

He hears the clatter of horses and guardsmen’s sabres on the square below. The Emperor will see the photographs and perhaps, this time, won’t tease him about his ‘weakness’ for symmetry. He always talks about London, where traffic and troop movements were the essential point. But, as Haussmann reminds him, ‘Parisians are more demanding than Londoners.’ He has been known to triple the width of an avenue for effect, and also, he would admit, to sabotage the paltry designs of the Emperor’s favourite architect, Hittorff. He may be a steam-roller but he understands the principles of beauty. A painting must always have a focal point and a frame, which is why it is now possible to stand in the middle of the Boulevard de Sébastopol and to see the Gare de l’Est at one end and the dome of the Tribunal de Commerce like a full stop at the other–except when the mists are rising from the Seine, filling the avenues and blurring perspectives, turning carriages and pedestrians into a procession of grey ghosts.

T

HE DOUBLE DOORS

are opened to admit His Imperial Majesty Napoleon III.

The man still has the dimensions of the prison cell about him. He lives in palaces but looks as though he could fit into a tiny space at a moment’s notice. There is something about his smallness that commands respect. Baron Haussmann will not be asked to die for his Emperor, but he is prepared to sacrifice his reputation, which is besmirched almost every day–by liberals and socialists, who forget that the poor now have more hospital beds and proper graves; by nostalgic bohemians, who forget everything; and even by his own social equals, who find the inconvenience of moving house too heavy a price to pay for the most beautiful city in the world.

The framed photographs have been arrayed on the table in geographical order.

This makes a nice change from the usual squabbles with architects. (The Emperor speaks in short sentences, like an oracle.) He has sat for many photographers, but this Marville is unknown to him.

The Baron explains–it is unclear whether it was his idea or the Historical Committee’s: Marville is the official photographer of the Louvre. He takes photographs of emperors and pharaohs, Etruscan vases, and medieval cathedrals that are being demolished and rebuilt; he records artefacts that have been disinterred and rescued from the past. Marville was commissioned to photograph the sections of Paris that are about to be buried and forgotten. It might be seen as archaeology in reverse: first the ruins, then the city that covers them up. A copy of the Plan was given to M. Marville, who then set off to erect his tripod at every designated site.

At this, the Emperor turns his head towards the Baron with what could be a quizzical smile: knowledge of the Plan (as their enemies point out) would allow a speculator to buy up properties before the City expropriates them and pays a handsome compensation. But Marville is an artist, not a businessman–so much is clear from the photographs.

They stand at the table and survey the scenes that are about to disappear. They see the wasted space, the lack of uniformity, the corners where rubbish collects and thieves lurk. They sense the provincial hush and the age-old habits. Sometimes, there are flecks that might be bullet-holes in the walls, and scratches on the plate that look like scraps of cloud above a battlefield, but mostly the images are sharp and clean.

They pause over one print in particular, though it has nothing of obvious interest. It shows the back end of a square that looks overpopulated and deserted at the same time. The Baron identifies the tenements on the right as the handiwork of one of his predecessors, Prefect Rambuteau, and makes a rumbling sound of satisfied disapproval. He points to the tenements wedged into the corner of the square and the Rue Saint-André-des-Arts. The photographer has captured the anaemic radiance that fills the Latin Quarter in the early morning. The light that bathes the facade of no. 22 only intensifies the gloom. Its shielded windows suggest some secret life behind.

The building has wooden blinds instead of shutters, hung out over the window railings, which means that the day is warm but not windy. This is the economical style that was used by Prefect Rambuteau in the 1840s, with grooves scored in the plaster to imitate expensive freestone, and, instead of a continuous balcony, iron railings at the foot of each window and a ledge no wider than a kerb. Baron Haussmann remembers the scene from his student days: the area of no particular shape, veering off from the Place Saint-Michel; the bookshop at no. 22 with the puddle in front of it. The image is so vivid that, without thinking, he glances down at his boots.

Only a man who had walked there a thousand times would know that the neighbourhood is bulging with books. No. 22 alone contains one hundred thousand volumes, advertised as

dépareillés

, which means they belong to broken sets. This is a bookshop that can make a mystery of any life. It once shared the building with the publisher of ‘la Bibliothèque Populaire’, a series devoted to antiquities: Chardin’s history of the East Indies; Chanut’s

Campagne de Bonaparte en Égypte et en Syrie

. This is where Champollion-Figeac, brother of the decipherer of hieroglyphics, published his famous treatise on archaeology.

The

quartier

has barely changed. From one of those windows at no. 22, Baudelaire looked out on his first Parisian landscape. He was seven years old. His father was dead, and his mother was still in mourning. He wrote to his mother in 1861 and reminded her of their time together in the Place Saint-André-des-Arts: ‘Long walks and never-ending kindness! I remember the banks of the Seine that were so melancholy in the evening. For me, those were the good old days…I had you all to myself.’

By chance, no. 22 appears on another of the photographs, further along the table, at the foot of an advertisement for kitchen stoves and garden furniture: ‘The Special Billposting and Sign Company is still at 22, Rue Saint-André-des-Arts.’ Some of those advertisements that upset the poet’s mind must have come from his childhood home at no. 22. Coincidences like this are unremarkable in a set of four hundred and twenty-five photographs. If Baron Haussmann notices any of those words on the walls on Paris, it is only because wall space is a source of revenue for the city, and because some of the words are the visible portents of his power: ‘

VENTE DE MOBILIER

’, ‘

FERMETURE POUR CAUSE D’EXPROPRIATION

’, ‘

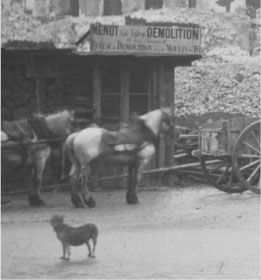

BUREAU DE DÉMOLITION

’.

T

HEY SPEND

much longer than they mean to, staring at the glassy image. The Emperor has no intention of inspecting all four hundred and twenty-five photographs, but he lingers over this one, as though trying to dissolve some difficult thought into the image. The Baron adjusts his position once or twice. He pictures the gaping space that will open up where the masonry blocks the view. He briefly imagines himself standing on the demolition site, recognizing the twisted metal remnant of that balcony in the centre of the picture–if such a cluttered mess can be said to have a centre. He imagines the Emperor’s compliment when he notices the columns of the Odéon Theatre neatly framed at the far end of the new Boulevard Saint-André.

As he wedges a finger under the photograph to turn to the next one, the Emperor raises his hand. Something has occurred to him…He sometimes asks odd questions, perhaps on principle or simply out of distraction, it is hard to tell. He wants to know where the people are. (Marville is not there in person to explain; he has sent a messenger with the photographs.) Why are those daylit streets so empty? Is the

quartier

already half-abandoned?

The answer is obvious. The streets are empty because anything that moves, disappears–the smoke from a pipe, a cart-wheel turning a corner, a bird fluttering down to the cobbles. All movement is lost in long exposures. But this is one of those false gems of historical wisdom (photography has made such rapid progress): the thought of a sitter forced to resist an itch, smile frozen, head clamped…

The first photographic image of a human being in the open air is the scarecrow figure of a man on Daguerre’s photograph of the Boulevard du Temple, taken from the roof of his studio in 1838. This lone pioneer in the photographic past seems to have stopped at the last tree before the corner of the Rue du Temple to have his shoes shined. Everyone else has vanished, along with all the traffic. But in 1838, the shortest exposure time for a daguerreotype was fifteen minutes. Unless the bootblack was unusually conscientious, rubbing and buffing until a faint image of his face appeared on the leather, the man must have been sent down by the photographer to stand still for as long as he could in the river of vanishing pedestrians, to give some human life to the scene.

In 1865, exposure times have been reduced to the blink of an eye. In 1850, Gustave Le Gray was photographing summer landscapes in forty seconds. In 1853, the Emperor’s photographer, Disdéri, removed and replaced the cotton pad in front of the lens as quickly as a conjurer waving his wand: ‘If I count to two, the print is over-exposed.’ He took razor-sharp pictures of children, horses, ducks and a peacock displaying its tail, though, for some reason, he could never make the Emperor’s eyes look focused. Twelve years later, some of Marville’s photographs show dogs going about their business, stuck to the pavement in perfect, four-legged focus.

The streets are empty because this is early morning. But even in the heart of Paris, despite Baron Haussmann’s thirty-two thousand gas lamps, the working day is still regulated by the sun. The horses are standing on their shadows, and the hour is later than it seems. There is still just one ‘business district’–around the new Opéra, where only bank managers and courtesans have nested in the expensive new apartments financed by men with close ties to Baron Haussmann’s son-in-law. Everyone else comes in from leafy

quartier

s in the west. Most Parisians commute to work from round the corner, from one room of the apartment to the next, or from the entresol to the shop below.

Baron Haussmann’s secretaries could produce the statistic in an instant: every minute, on the biggest and busiest boulevards–Capucines, Italiens, Poissonnière, Saint-Denis–at the busiest times of day, fewer than seven vehicles go past in both directions. On the Rue de Rivoli and the Champs-Élysées, one vehicle passes every twenty seconds. Just behind the photographer’s right shoulder, on the new Pont Saint-Michel, only the blind, the deaf, the lame, the distracted and the dithering are in danger from the traffic. Baudelaire was already suffering from premature old age when he wrote ‘To a Passer-By’ in 1860:

The deafening street was roaring all around me…

The woman whose eye he catches is ‘agile’ and ‘fleeting’, ‘lifting and swaying the hem and scallop of her dress’. She is dressed in formal mourning but still able to cross the road with dignity.

A flash…then darkness!…Shall I never see you again

Until eternity begins?

A century later, the passer-by and the poet might have had time to start a conversation while they waited for the lights to change. They might have sat down at the pavement café, or stood still in the rushing crowd. A photographer with a high-speed camera might have caught them kissing…

Baron Haussmann leaves the Emperor’s question unanswered. The Emperor is probably thinking of London–the last place where he deigned to notice the life of the streets, and where he acquired his irksome predilection for ‘squares’ and tarmacadam, which is expensive and difficult to maintain.