Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (11 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

Front Street today, showing Penn's View Hotel/Ristorante Panorama, Old City Mercantile (Girard's Warehouses) and the Nathan Trotter and Frank Winne buildings. All structures are from the early to mid-1800s. Note how I-95 cuts off Front Street.

Photo by the author

.

S

TEPHEN

G

IRARD

'

S

W

ILL

(I

OF

III)

Stephen Girard left the City of Philadelphia some $500,000âan immense sum in the 1830sâfor use in improving the riverfront area east of Front Street. Almost the whole rise in importance of the Port of Philadelphia is traceable to this bequest.

Girard was obviously well acquainted with Penn's stairways, given that he lived among them and one abutted his home. In his will, after explaining his understanding of how the bank steps and alleys came to be public property, Girard expressed dismay that some were no longer accessible:

[O]

wing to neglect or to some other cause on the part of those who have had the care of the city property, several encroachments have been made on them by individuals, by wholly occupying, or building over them, or otherwise

.

This was a time when both rich and poor lived alongside one another, a common occurrence in Philadelphia until the end of the 1800s. So it's not surprising that Girard was concerned about the detrimental effect this was having on the health of people who lived on the crammed riverbank: “[I]n that way, the inhabitants, more particularly those who reside in the neighbourhood, are deprived of the benefit of that wholesome air, which [the alleys'] opening and cleansing throughout would afford.”

Some modern accounts have it that the bank steps were built under the terms of Girard's will, but this is not the case. Later chapters will address the will further.

O

LD

C

ITY

M

ERCANTILE

/P

ENN

'

S

V

IEW

H

OTEL

/R

ISTORANTE

P

ANORAMA

Delaware Avenue in front of Pier 3 Condominium occupies the space where Stephen Girard's docks and wharves were located long ago.

Some of his warehouses still stand on the west side of Front Street (20â30 North Front) and have been converted into residential apartments. Called the Old City Mercantile, this development is a splendid restoration of a group of Greek Revivalâstyle buildings that had been on the brink of collapse for years. They were originally constructed between 1828 and 1834 by Girard and his estate.

Penn's View Hotel is next on Front Street on the south side of Church Street. This boutique hotel is home to Ristorante Panorama, an eatery serving fine Italian cuisine. Wine lovers around the globe have heard about its cruvinet, the world's largest wine preservation and dispensing system.

The structure that makes up the Penn's View Hotel was built as a shipping warehouse in 1828. It became a hardware store around the turn of the twentieth century and then a coffeehouse in the 1950s. The building sat vacant until chef Carlo C. Sena (1922â2011) bought and refurbished it as a hotel in 1989. Penn's View is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Sena had previously opened La Famiglia Ristorante at 8 South Front in 1976. This was a daring undertaking since Old City Philadelphia had not yet become a dining destination. The restaurateur arrived in Philadelphia as an Italian immigrant only nine years before. Carlo Sena found success only a few doors away from where Frenchman Stephen Girard and Quaker Nathan Trotter had found theirs.

Other dining venues along Front Street include: Swanky Bubbles at 14 South Front; Spasso Italian Grill a few doors south; Downey's at Front and South since 1976; Catahoula Bar & Restaurant at 775 South Front; and the dozens of other places in Old City, Society Hill and Queen Village. Parking, the scourge of the modern city, took down many old commercial buildings to allow for convenient access to these establishments.

T

HE

D

ELAWARE

A

VENUE

E

LEVATED

(

THE

F

ERRY

B

RANCH

)

Clifford's Alley was later called Filbert Street, and the Filbert Street Steps were apparently at 37 North Water. They were removed in 1907â08 by the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRTC) for the building of the Market Street Subway. The following is from a PRTC report issued in 1908:

Filbert Street, an 8 foot passageway for pedestrians, was closed by authority of Councils and made the site of the abutment at the south end of the concrete viaduct. Front Street is so much higher than Water Street that the second stories of the properties facing on Water Street formed the cellars on the Front Street side

.

The “8 foot passageway” was the Penn stairwell at Filbert Street.

The Market Street Subway turned north at Front Street and exited the ground at a transition portalâbetween the subway and elevated portionsâjust north of Market Street. The shed covering this portal was used as a freight station for the PRTC's trolleys, which ran on both Market and Front Streets. The Front and Market Station was a lively spot in the days when freight trolleys delivered milk, newspapers, packages and other time-critical items.

The Market Street Line continued up an incline to an elevated steel structure and then turned 180 degrees in hairpin fashion above Arch Street to reach Delaware Avenue. It then proceeded over the boulevard's southbound lanes all the way to South Street, where the line stub-ended. This was the Delaware Avenue Elevated, also known as the “Ferry Branch” or “Ferry Line,” since its stations served the many ferries to New Jersey. There were two stops: one at Market-Chestnut and another at South Street.

The Ferry Line lost passengers as ferry traffic diminished after the Delaware River Bridge opened in 1926. Most ferries had ceased operating by 1938, and the Ferry Branch stopped running the following year. The elevated structure atop Delaware Avenue was then dismantled. Not a single trace remains.

The Delaware Avenue El alternated service to Sixty-ninth Street with the Frankford Elevated Line, which connected to the Market Street Subway at Arch Street. Built by the city between 1915 and 1922, the Frankford Line ran north atop Front Street toward Philadelphia's Frankford sectionâand still does so.

A view of the waterfront looking north about 1930, showing the Delaware Avenue Elevated atop Delaware Avenue, the El's terminus at South Street, the density of finger piers along the river and the Ben Franklin Bridge.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

The Delaware Avenue Elevated, looking south from Chestnut Street.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

Construction of Interstate 95 forced the removal of the transition portal on Water Street. The portal's siteâonce the location of the Filbert Street Stepsâwas then covered by the freeway. Furthermore, the Frankford El's overhead structure on Front Street was removed for over a mile north of Arch Street in the mid-1970s. (This stretch of Front had not seen the light of day in half a century.) The route of the MarketâFrankford line was relocated to within the median of I-95 during the highway's construction.

P

IER

3 N

ORTH AND

P

IER

5 N

ORTH

(

THE

N

EW

G

IRARD

G

ROUP

P

IERS

)

The Department of Wharves, Docks and Ferries built Piers 3 and 5 North in 1922 and 1923 as the last element of a fifteen-year phase of improvements to the Port of Philadelphia. These warehouse piers were specifically designed to: 1) handle ships with much greater draw, 2) enable the loading and unloading of more than one ship simultaneously and 3) facilitate the rapid transfer of cargo to railroads, wagons and trucks. The city spent $4.5 million to construct these sister piers.

Piers 3 and 5 were raised on the site of several obsolete wooden wharves that were put up in the late nineteenth century with money left to the city by Stephen Girard. These old piers were dubbed the “Girard Group” (or “Girard Piers”), so the replacement structures were officially called the New Girard Group Piers. Completed first, Pier 3 was officially dedicated by Mayor J. Hampton Moore on June 29, 1922.

The Clyde Steamship Company, which provided passenger and freight service between New York and southern ports, operated both the old and the new piers. Philadelphia was a port of call for the Clyde Lines for years and years.

The New Girard Piers were made of steel and concrete with brick and limestone facing and stand on timbers driven into the riverbed; some eight thousand poles support Pier 3 alone. Both structures extend about 550 feet into the Delaware River channel, which is as far as federal law allows to ensure safe navigation. (Being a navigable interstate river, the Delaware falls under federal jurisdiction.)

This is how cargo was transferred between ships and docks in the old days.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

Municipal Piers 3 and 5 came about right at the zenith of the central Delaware River corridor's role in Philadelphia's maritime activity, a period when the slogan “Ship Via Philadelphia” was a city mantra. The Great Depression diminished port operations considerably, although things picked up during World War II. But that was the last hurrah for this portion of the Delaware as a shipping center.

After decades of faithful service, Piers 3 and 5 North succumbed to more modern methods of port operations and cargo handling. They lingered on into the 1970s, after which they stood forsaken and neglectedâand rat infestedâsquarely in the area that was then being transformed into Penn's Landing.

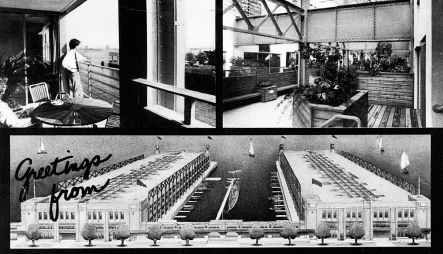

In a stroke of genius and a leap of faith, a group of developers began converting the two outmoded warehouse piers into residences beginning in 1985. While plans were drawn, the now old New Girard Group piers were added to the National Register of Historic Places in recognition of their early Art Deco architecture. A component of the adaptive reuse project was removing the roof of both buildings to create a tree-filled atrium in each complex. The ground floor of each structure, where rail cars used to enter, is now parking.