Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (14 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

Watson reported that “[i]n 1721, the Grand Jury present, as out of repair and dangerous the Crooked Billet steps, above Chestnut street.” What finally happened to these stairs is unknown, but they seem to have been closed in the mid-nineteenth century, whereupon the ground was likely taken over by neighboring property owners. These environs are all topped by Highway 95 today.

P

HILIP

S

YNG

J

R

.

AND

B

EN

F

RANKLIN

'

S

J

UNTO

Like carver William Rush, silversmith Philip Syng Jr. (1703â1789) was one of countless craftsmen who lived and worked along Front Street. He came to America in 1714 and later moved to this vicinity, where he obviously saw Benjamin Franklin around town. The two became friends. Syng helped Franklin with his electrical research and even made the static electricity machine with which the great scientist experimented in 1747.

Syng joined the Junto, the club of tradesman that Franklin organized in 1727 and which became the first discussion and intellectual club in America. The men of the Junto founded many of Philadelphia's longstanding public and private associations and organizations. They were familiar with the Delaware waterfront, as most lived and earned their livelihoods not far from the river.

Philip Syng designed and crafted an ornate silver inkstand for the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1752. It was this inkstand that members of the Second Continental Congress used to sign the Declaration of Independence and delegates to the Constitutional Convention used to sign the United States Constitution. Now part of the collection at Independence Hall, the Syng inkstand is surely (for what it's worth) the most important inkstand in the world.

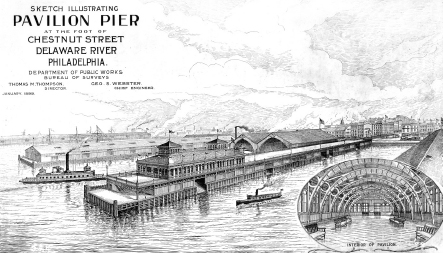

Plans for Chestnut Street Pier, with an inset showing the interior of the pavilion.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

T

HE

C

HESTNUT

S

TREET

P

IER AND

I

TS

N

EIGHBORS

New finger piers were constructed between Market and Chestnut Streets after Delaware Avenue was enlarged to its current width by 1900. Pier 1 South was a covered timber-crib, earth-filled structure that was leased to a contractor for use in moving street dirt and ashes via barges. Pier 3 South processed fruit, grain and general freight for steamship lines trading to foreign and domestic ports.

Pier 5 South at Chestnut Street was owned by the city, which leased it to steamboat companies that handled food and wares. Built in 1899, Chestnut Street Pier had a steel superstructure and, like Race Street Pier, an ornate Victorian pavilion on its upper deck where people could relax by the Delaware. These public places were intended to act as parks alongside the river's edge.

A footbridge over Delaware Avenue provided quick access to the pavilion from the Market-Chestnut station of the Delaware Avenue El. The pavilion was removed in 1922 when Pier 5 South was modernized to become headquarters for the Department of Wharves, Docks and Ferries. Next to Pier 5 were ferry slips of the Delaware River Ferry Company of New Jersey, a service owned by the Reading Railroad.

Along with nearby warehouses, all the piers from Market to South Streets were removed in the 1960s to make way for Penn's Landing and Interstate 95 on this stretch of the river. The Philadelphia waterfront had become moribund by then, long past its prime as a commercial shipping district.

12

C

HESTNUT TO

W

ALNUT

A W

ELCOMING

M

ANSION

(

AND

P

ARK

)

FOR

W

ILLIAM

P

ENN

N

EAR THE

B

IRTH OF THE

M

ARINES

Wynne Street, the first name of Chestnut Street, was taken from Thomas Wynne, William Penn's personal physician and a first purchaser of Philadelphia. Wynne's lot was at Front and Chestnut.

S

AMUEL

C

ARPENTER

'

S

W

HARF

Samuel Carpenter (1649â1714) was an English Quaker from Barbados, a friend of William Penn and a first purchaser. He had bought a small lot along the Delaware between Chestnut and Walnut Streets before coming to Penn's settlement. After his arrival in 1683, he constructed Philadelphia's first wharf there, along with a cottage overlooking the river.

Carpenter's Wharf was a notable landmark in the city's earliest days. William Penn wrote in 1683, “There is a fair key [dock] of about 300 foot square built by Samuel Carpenter to which a ship of five hundred tuns [tons] may lay her broadside.” Gabriel Thomas states in his chronicle

An Historical and Geographical Account of the Province and Country of Pennsylvania

(1698), “There is also a very convenient Wharf called Carpenter's Wharf which hath a fine necessary Crane belonging to it.” This cargo crane was widely praised in writings of the day.

The wharf was expanded over the years with numerous storehouses and other commercial structures, some of which stood for over a century.

C

ARPENTER

'

S

S

TAIRS

William Penn conveyed a larger (204-foot-wide) bank lot to Carpenter on August 4, 1684, the day after issuing his decree that bankers could develop their riverbank property as long as they provided for public access to the Delaware River. This Carpenter plainly did. In an undated letter written that year, he informed Penn:

I am willing to make and maintain forever, 2 pair of stairs, viz., 1 pair from the water up to the wharf and the other from the wharf to the top of the bank, for the comodius passing and repassing of all persons to and from the water, free forever

.

And so were built Carpenter's Stairs, mentioned often in literature. The quote confirms that these steps began on the high river bluff and proceeded down past Carpenter's Wharf and into the Delaware itself. Carpenter's Stairs were on the line of Norris' Alley, later Gothic Street, a modest lane that subsequently became part of Sansom Street.

Sailors, merchants, servants and even slaves climbed Carpenter's Stairs for at least 125 years. Evidence suggests that they lasted until sometime between 1825 and 1847 and that the ground they occupied was incorporated into bordering property tracts. All of this ground is now covered by I-95.

M

ILITARY

M

ATTERS

(II

OF

V): T

UN

T

AVERN AND THE

U.S. M

ARINES

Samuel Carpenter and his brother, Joshua, opened the Tun Tavern brew house and inn at King (Water) Street and Tun Alley in 1685. (The old English word “tun” means a barrel or keg of beer.)

The first meetings of the St. John's No. 1 Lodge of the Grand Lodge of the Masonic Temple were held there in 1732. Benjamin Franklin was its third grand master. The Masonic Temple of Philadelphia recognizes Tun Tavern as the birthplace of Masonic teachings in America. Plus, the St. Andrews Society, a charitable group devoted to assisting Scottish immigrants, was founded there fifteen years later.

Tun Tavern was also, according to tradition, where the United States Marine Corps held its first recruitment drive. On November 10, 1775, the First Continental Congress commissioned Samuel Nicholas, a Quaker innkeeper, to raise two battalions of marines in Philadelphia. The tavern's manager, Robert Mullan, was the head recruiter. Prospective volunteers flocked to the place, enticed by cold beer and the opportunity to join the new corps. The first Continental U.S. Marine unit was composed of one hundred Rhode Islanders commanded by Captain Nicholas. Some three million U.S. Marines have been exposed to the significance of Tun Tavern. Each year on November 10, U.S. Marines worldwide toast the place.

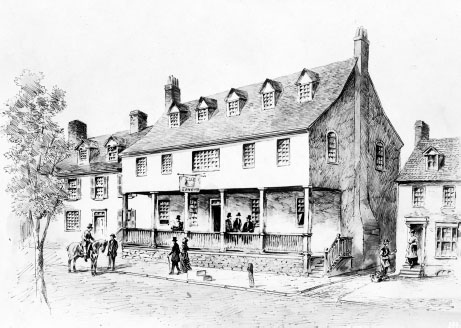

The Tun Tavern, by Frank H. Taylor. This drawing dates from about 1922, almost 150 years after the place burned down.

The Library Company of Philadelphia

.

Fire destroyed the revered colonial inn in 1781. The Delaware Expressway covers the site nowadays.

C

ITY

T

AVERN

Tun Tavern may be gone, but a reasonable facsimile stands at Second and Walnut. This is the City Tavern, a reconstruction of Revolutionary America's finest tavern.

The original City Tavern was put up in 1773 by a group of Philadelphia's most financially and politically prominent individuals who felt that the city deserved an excellent tavern, coffee shop and inn that reflected its status as the most cosmopolitan city in British North America. Merchants' Coffee House, as it was first called, was considered the best establishment of its kind in the colonies. Never one to over praise, John Adams called it “the most genteel” tavern in America.

City Tavern gained fame as the gathering place for members of the Continental Congresses and the Constitutional Convention and federal government officials from 1790 to 1800. The First Continental Congress initially gathered there before moving to Carpenters' Hall. The inn became Philadelphia's commercial center and stock exchange after the London Coffee House became too small and outdated for local businessmen.

Eclipsed as a center for business and politics, City Tavern was demolished in 1854 after a tragic fire involving a bridal party. The present structure is a faithful reconstruction by the National Park Service dating from 1975â76. It has since operated as an eighteenth-century-style tavern serving lunch and dinner daily.

W

ELCOME

P

ARK AND THE

S

LATE

R

OOF

H

OUSE

Welcome Park is directly across Second Street from City Tavern. This urban courtyard presents a re-creation of Thomas Holme's 1682 map of Philadelphia, with the city's street grid laid in marble. A miniature version of the statue of William Penn that crowns Philadelphia City Hall stands on a pedestal in the center. Penn's plans and promotions for Philadelphia are illustrated on a wall enclosing the square, as is a timeline of his life. The place was named after his ship,

Welcome

, which brought Penn and over one hundred passengers, mostly Quakers, to America in 1682.

Welcome Park was dedicated exactly three hundred years later on the site of the Slate Roof House, the famed mansion that Penn used as a city residence during his second visit to America (1699â1701). It was there that Penn wrote and issued his “Charter of Privileges.” This progressive framework for Pennsylvania's government became the model for the United States Constitution and is still the basis of free governments all over the world.

James Logan, the secretary of the Proprietary, also lived in the Slate Roof House and administered the colony of Pennsylvania from there between 1701 and 1704. The mansion became a crumbling object of interest prior to being taken down in 1867.

The Slate Roof House, today the site of Welcome Park.

Author's collection

.