Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (13 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

Christ Church steeple was financed first by subscription and then by two lotteries managed by Benjamin Franklin and other leading Philadelphians. The slim white tower was built by Robert Smith and was finished in 1755, when bells from Great Britain were installed. It pierced the sky at 196 feet high and was the tallest structure in North America for almost one hundred years. John Adams wrote in his diary of climbing the tower's ladders to gaze upon the new nation in 1776.

Christ Church and its steeple in 1939. The church looks the same today.

Library of Congress (HABS)

.

The “Philadelphia Steeple,” as it was commonly called, could be seen from miles away by seafarers sailing up the Delaware toward Philadelphia and was a beacon that guided ship captains. Even now, Christ Church steeple is a prominent landmark on the Philadelphia skyline.

Christ Church could no longer be an Anglican church due to the American Revolution. An agreement was reached between English officials of church and state and the U.S. Congress and American Anglicans to establish the Episcopal Church in America. As a result, this church is the birthplace of the Episcopal Church in the United States.

The baptismal font at Christ Church is the very one in which William Penn was baptized in 1644. It was sent to Philadelphia in 1697 from All Hallow's Church in London.

O

LD

C

ITY

P

HILADELPHIA

Second and Market is still the heart of Old City Philadelphia, one of the most historic neighborhoods in the United States. Besides being among the first areas settled by Europeans in the mid-1600s and later the core of William Penn's town on the Delaware, this was undoubtedly the nation's first great crucible of commerce, finance, culture, religion and government.

The original part of Philadelphia became a temporary home to the new federal government in the eighteenth century, as well as the home and workplace of historical figures like Franklin, Washington, Adams and Girard. Both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were drafted and approved in this neighborhood. And Bank Row on lower Chestnut Street became the nation's primary financial districtâthe first Wall Street, as it were.

The old part of town lost its standing as the city expanded in the 1800s. It became the commercial center of Philadelphia, filled with stores, hotels and light manufacturing. Well-heeled Quakers moved out and immigrants moved in. Many Old City residents left the area in the twentieth century as it evolved into a wholesale distribution center (focusing primarily on restaurant kitchen supply). By the 1960s, the worn-out district had completely outlived its usefulness for commercial/maritime activity, much like the bordering waterfront.

In 1971, the Philadelphia Planning Commission surveyed eight hundred warehouses and other structures and found that over half were decayed, vandalized or unoccupied. Following some favorable zoning changes, most of Old City's vacant and dilapidated nineteenth-century buildings were rehabilitated. Residents, retail and restaurants moved in where they had not been for a long time.

Today, Old City Philadelphia has over fifty restaurants serving every possible cuisine. Boutique stores provide shoppers with a wide range of choices, including the largest concentration of art galleries on the East Coast. All this is set in one of the country's greatest collections of cast-iron industrial loft buildings. The neighborhood's historical allure and its contemporary flair make Old City the place to see what's new in Philadelphia. A sometimes-boisterous crowd usually does so on Friday and Saturday nights.

A good example of this change is the 100 block of Chestnut Street. It retains much of its commercial look from one hundred years ago, including the Belgian-blocked surface. But the street's structures used to house mercantile establishments and the like, not ritzy nightclubs and Turkish restaurants (with belly dancing).

Note that there's no

e

in Old City. “Olde City” is an affectation that started accidentally in the 1970s.

F

ERRIES

C

ROSSING THE

D

ELAWARE

(II

OF

II)

Several railroads ran through New Jersey to coastal towns on the Atlantic Ocean, taking passengers to seaside resorts for a day, weekend or week of leisure. The railroads operated ferry routes plying from Philadelphia to Camden and other Jersey towns on the Delaware River. The ferry terminals of these railroads were concentrated near the Market Street Wharf.

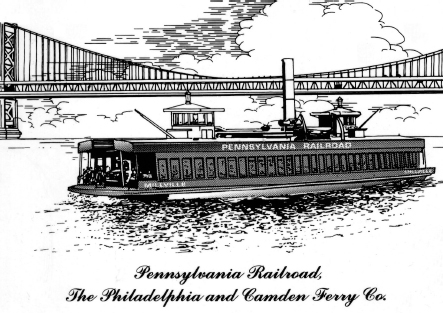

The Pennsylvania Railroad's ferry unit was the Philadelphia and Camden Ferry Company, known far and wide for its fleet of eight steam ferries that transported passengers and vehicles to Camden's Federal Street Terminal. Walt Whitman, the Good Gray Poet, was a frequent user of this ferry, visiting from Camden to stroll around Philadelphia or to merely sit at the docks and watch people come and go.

The West Jersey Railroad, a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad, gained control of the Camden and Atlantic Railroad in 1883. Thirteen years later, the Pennsylvania consolidated its southern New Jersey lines into the West Jersey and Seashore Railroad. This is how the Pennsylvania Railroad wound up owning most of the ferry landings near the Market Street Wharf by the 1900s.

A ferry of the Pennsylvania Railroad's PhiladelphiaâCamden line.

Author's collection

.

Delaware River ferries carried people, cars, trucks and busses well into the twentieth century. Over 100,000 passengers were transported daily at the height of ferry business in 1925. There was a departure from each side of the river every three minutes during peak periods. Over five million vehicles were carried at the apex of ferry activity.

The Benjamin Franklin Bridge and the assent of the automobile supplanted all the ferries that had crossed the Delaware since before the arrival of William Penn. This happened fairly quickly after the Second World War. The last regular PhiladelphiaâCamden ferry to operate was the Pennsylvania Railroad's, which held out until 1952âafter 114 years of nonstop operation.

The bridge and the automobile also diminished railroad traffic between Camden and Atlantic City. The Depression did not help matters. So, in 1932, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Railroad joined their southern Jersey operations into one company, the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines. Service lingered on until the 1970s.

The Philadelphia and Camden Ferry's four-slip terminal's head house at the base of Market Street was built in the 1890s by the Pennsylvania Railroad. This elaborate Victorian structure with a four-sided, clock-equipped cupola appears in many old photographs of Philadelphia's waterfront. It became a food market in the 1950s and was ultimately removed for the construction of Penn's Landing.

The Pennsylvania Railroad's PhiladelphiaâCamden Ferry Terminal about 1910. Picture taken from the Delaware Avenue El.

Library of Congress

.

A lone tourist-oriented ferryboat between Penn's Landing and the Camden waterfront is a small connection to the past. This is the RiverLink Ferry, operated since the 1990s by the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation.

T

HE

P

OLLUTED

D

ELAWARE

In the heyday of ferry service, as many as 200,000 people would begin their annual trip to New Jersey's shore towns from the ferries on the central Delaware riverfront. Some would wait hours for the fifteen-minute ride across the channel. The trip was often unpleasant, as the Delaware had earned a reputation by the mid-twentieth century for being dirty and smelling bad.

Upstream industries had polluted the water to the point that longshoremen became ill from the smell of hydrogen sulfide. The shad that the Lenni-Lenape and others once harvested died in scores as the oxygen-depleted river itself died. Saturated with chemicals and other pollutants, the Delaware had not frozen over in a long time, let alone two feet thick as in the days when ice skaters and sleighs had a field day. It was so bad that paint would peel off the hulls of ships. People avoided being on or near the river unless they absolutely had to.

The Delaware River's industrial saga was much the same as that of Pegg's Run or Dock Creek (discussed later). Yet unlike those polluted local streams, the river was a beneficiary of the Environmental Revolution of the 1970s, becoming cleaner after federal and state environmental regulations took effect. Philadelphia's de-industrialization, for good or bad, also helped reduce water pollution in the Delaware. Shad and other fish have returned, and it's not unusual these days to see people fishing along the water's edge.

11

M

ARKET TO

C

HESTNUT

O

F

A

NCIENT

T

AVERNS AND

F

RANKLIN

'

S

F

RIENDS ON THE

C

ENTRAL

R

IVERFRONT

Interspersed among the major streets of Old City are a number of charming alleys and courtyards with handsome commercial and residential structures from the nineteenth century. It's well worth wandering down Bank, Bread, Church, Cuthbert, Ionic, Quarry or Strawberry, all narrow and quaint in the Old Philadelphia way.

T

HE

B

LACK

H

ORSE

âT

AVERN AND

S

TEPS

Black Horse Alley, an extremely narrow passageway a bit south of Market between Front and Second Streets, is an unnoticed alley of special interest. Originally called Ewer's Alley, it was renamed from the sign of a tavern later in the middle of that city block.

There were two Penn stairways between Chestnut and Market Streets. The northernmost one was the Black Horse Alley Steps, a continuation of Black Horse Alley. It's likely that these bank steps survived until the building of I-95, for they do appear on a 1962 Philadelphia Land Use map.

Also within the block is Letitia Street, once at the center of Letitia Court. This courtyard was intimately connected to the lore of William Penn. He reserved the whole city block for his personal use and then gave it to his daughter, Letitia, who later sold it off piecemeal. One parcel became home to the London Coffee House. The full story of Letitia Court is part of a larger tale too involved to convey here.

T

HE

C

ROOKED

B

ILLET

âT

AVERN AND

S

TEPS

The other embankment staircase on this block was the Crooked Billet Steps, as it led to a tavern by that name on the Crooked Billet Wharf. This pier extended from Water Street onto the Delaware River roughly one hundred feet north of the bottom of Chestnut Street. The narrow space behind the tavern coupled with the wharf's irregular shape caused many peopleâmaybe some inebriatedâto fall into the river and drown.

Alice Guest arrived in Philadelphia in 1683 and began keeping a saloon in a cave on her bank lot facing the Delaware. Within ten years, she had built a wharf, warehouses and an inn: the Crooked Billet. This place was where Benjamin Franklin had his first hot meal and spent his first night in Philadelphia.