Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (16 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

The creek was anticipated to have been a convenience to inland inhabitants of Philadelphia by affording easy transportation of food and goods into the interior of Penn's City of Brotherly Love. The tides regularly flowed inward as far as Chestnut Street, and the Coocanocon was navigable for sloops and schooners as far west as Third Street.

The mouth of Dock Creek was a swampy salt marsh skirted by a low sandy beach. A drawbridge was built to connect the north and south portions of Front Street over the inlet. Wooden bridgesâlater replaced with stone archesâwere placed at Second, Third, Chestnut and Market Streets. Small ships with masts could pass under these spans at low tide.

Some pioneers lived in dugouts along the Coocanocon. The water was clean, the soil was grassy and the view of the Delaware was pleasant. Deer roamed nearby. As merchants flourished in Philadelphia, it became fashionable for them to build mansions on either side of Dock Creek, with lawns and gardens descending toward the banks. The Slate Roof House was one of these. When William Penn came down the Delaware from Pennsbury Manor in Bucks County to stay at the mansion, his boat would be rowed up the creek.

Breweries, lumberyards, slaughterhouses and tanneries were also built along Dock Creek. These industries discharged their putrid refuse into the stream, while the general public used it as a waste receptacle for chamber pots and the like. Like Pegg's Run, the tidal watercourse became polluted and sluggish.

The standing water of this open sewer became a civic concern and was blamed for a variety of public health problems. One of the earliest visitations of yellow fever in Philadelphia was supposed to have had its origin in the creek's filth. A good deal of controversy ensued, much of it cultivated by Benjamin Franklin in 1739, perhaps to initiate a public works project that would improve the cityâor maybe just to sell his newspapers.

Dock Creek's main branch was culverted and paved over in sections beginning in the mid-1700s. The east part of the main branch was confined within stone walls and arched with bricks, while the western part and the secondary branches were filled in, all in keeping with a series of ordinances enacted over the years beginning in 1762. One in 1784 ordered the laying of paving stones to “form a public highway known by the name of Dock Street.”

All this explains why Dock Street is a severely curved street in a city reputed for not having curved streets. Like Willow Street to the north, it follows the course of an old waterway. Dock Street was completed west of Front Street by 1821. The part between Front and the river was finished by 1839, when the first incarnation of Delaware Avenue was laid. Besides being curved, Dock Street is unusually wide (about one hundred feet), reflecting the original breadth of Dock Creek.

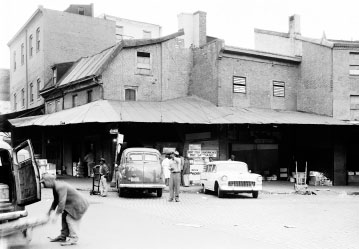

Dock Street eventually became Philadelphia's primary food market and served in that capacity for almost a century. As such, it became as dirty as the creek it replaced. Grimy warehouses and market stalls with tin roofs over the sidewalk lined both sides of the Belgian-blocked street for decades. Food of all kind was unloaded from ships that docked nearby. Dock Street teemed with sellers and buyers and their horse-drawn wagons in the morning. By afternoon, it was desertedâexcept for the rats.

The crowded food distribution center on Dock Street about 1908. This was the street in its heyday. Trucks later made the scene even busier.

Library of Congress

.

When larger motorized trucks replaced smaller wagons, the street was simply not able to handle the traffic. This state of affairs ended in 1959 when the sprawling Food Distribution Center opened on Packer Avenue in South Philadelphia. All the old food warehouses were torn down as Society Hill Towers and the Sheraton Society Hill took over Dock Street.

T

HE

B

LUE

A

NCHOR

T

AVERN

At the mouth of Dock Creek on the Delaware was the Blue Anchor Landing, which functioned as Philadelphia's main public wharf for decades. It was named after the Blue Anchor Tavern, a renowned inn that was under construction but already in business when William Penn first came to Philadelphia in 1682.

Penn arrived by barge from the downriver town of Chester, then called Upland. The tradition that he had a glass of ale at the Blue Anchor when he came ashore did not harm his standing among even the most pious members of the Society of Friends.

The Blue Anchor was a combination beerhouse, merchant exchange, grain market and post office. Its story was written by Thomas Allen Glenn and published in 1896 in the

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

:

For many years previous to William Penn's proprietorship there had been at Philadelphia (later so called) a constant landing of traders and of those inhabitants of West Jersey who were accustomed to go down to the sea in ships. The favorite landing-place was on the bank of the Delaware, between the present Walnut and Dock Streets, and it was directly back of this landing, on the higher bluff, that the Blue Anchor Tavern was subsequently built

.

The first building known as the Blue Anchor Tavern was of brick, was sixteen feet front by about thirty-six feet long, and stood directly in the middle of the present Front Street, then Delaware Front Street, about one hundred and forty-six feet north of Dock Creek, now Dock Street. In front of the Blue Anchor was the primitive wharf whereat Penn came ashore on his arrival from Chester, and which he erected into a public landing-place for the inhabitants of Philadelphia forever

.

The saloon and its landing stood directly in the middle of the present Front Street, about 150 feet north of the former Dock Creek. This would be just a bit north of the current-day Dock Street. As the riverfront developed, the Blue Anchor moved to replacement structures closer to Dock Creek twice, the last time in 1690. This place was a house at the end of a line of row homes put up by builder Thomas Budd. The pub continued to serve fishermen and other customers until 1810, when it was taken down.

Many other taverns and coffeehouses for the benefit of seafaring men were located along this strip of the Delaware during the city's younger days. These establishments were more than merely places to drink and dine. They were where people transacted business, argued politics, got the news and otherwise socialized. Water Street linked them together, all the way to Penny Pot Tavern roughly a mile north.

T

HE

M

AN

F

ULL OF

T

ROUBLE

T

AVERN

At Second and Spruce is a peculiar old Philadelphia pub that still stands: the Man Full of Trouble Tavern. First named the “Man Loaded with Mischief,” it was built in 1759 along with the adjacent house. This is the only surviving pre-Revolutionary tavern in the city.

The widow Martha Smallwood managed the tiny place in the 1790s, as that was when Philadelphia authorities would award tavern licenses only to “widows and decrepit men of good character.” That was also the time when there was one saloon for every fifty men in town.

The Man Full of Trouble was subsequently used as a hotel and wholesale chicken market, surrounded by other ramshackle houses and shops. The low-ceilinged building was on the verge of falling down before a private foundation restored it as a museum in 1965. Unfortunately, it's been closed to the public since 1996. At one time surrounded by unassuming buildings, the tavern now sits all aloneâbut with Society Hill Towers looming high above.

The amusing tavern sign outside the building depicts a dour sea captain with a monkey on his shoulder and a parrot on his hand, walking arm in arm with a genteel lady holding a hatbox. The original sign featured a gaudy woman hoisting a glass of bubbly while carried on the sagging shoulders of an unhappy sailor.

The closed but still standing Man Full of Trouble Tavern. The tavern itself is on the right.

Photo by the author

.

The Man Full of Trouble Tavern in 1958, when it was unrecognizable as a food wholesale place and surrounded by tattered buildings, much like itself.

Library of Congress (HABS)

.

P

IRATES AND

B

URIED

T

REASURE

Besides the dutiful William Penn, the pirate Edward Teach (1680â1718), otherwise known as Blackbeard, was a patron of the Blue Anchor Tavern. Indeed, it was common to see pirates of the Atlantic Coast, including Blackbeard and William “Captain” Kidd (ca. 1645â1701), openly swagger along Water Street and vicinity. Working and retired sea robbers liked being in Philadelphia because of the mild temper of Quaker justice.

But Penn, living in England at the end of the seventeenth century, did not endorse this. In 1697, he wrote to his American agent, William Markhamâwhose daughter married an alleged pirateâthat Londoners maintained that Philadelphians “not onlie wink att but imbrace pirats, shipps and men.” While the Pennsylvania Assembly denied this accusation, it did respond by passing a stringent law for the suppression of piracy and trading with or harboring buccaneers. But this did not halt Blackbeard's nefarious activities or his visits to Philadelphia. The same goes for other pirates.

Rumors of buried treasure along Philadelphia's waterfront persisted for hundreds of years. Watson claimed that a pot of money (at least $5,000) was once found buried in the cellar of a tavern at Front and Spruce Streets. Plus, many people hunted and dug for pirate plunder around where Fairmont Street met Front Street and also along Pegg's Run.

T

HE

F

LOATING

C

HURCH OF THE

R

EDEEMER

The Seamen's Church Institute of Philadelphia was founded in 1843 to address the needs of both saints and scoundrels visiting ports on the Delaware River. The institute, now at 475 North Fifth Street, has had many offices over the years, but its first “building” was actually a boatâthe

Floating Church of the Redeemer

. This unusual and impressive vessel was usually moored at the foot of Dock Street in the early 1850s.