Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (39 page)

Chrystie’s boat has lost an oarlock and is drifting helplessly downstream while one of his officers attempts to hold an oar in place. None of these regulars is familiar with the river; all are dependent upon a pilot to guide them. But as they come under musket fire from the Canadian bank the pilot, groaning in terror, turns about and makes for the American side. Chrystie, wounded in the hand by grape-shot, struggles with him to no avail. The boat lands several hundred yards below the embarkation point, to which Chrystie and the others must return on foot.

In Solomon Van Rensselaer’s later opinion, this is the turning point of the battle. Chrystie’s return and the heavy fire from the opposite shore “damped the hitherto irrepressible ardor of the militia.” The very men who the previous day were so eager to do battle—hoping, perhaps, that a quick victory would allow them to return to their homes—now remember that they are not required to fight on foreign soil. One militia major suddenly loses his zest for combat and discovers that he is too ill to lead his detachment across the river.

At the embarkation point, Chrystie finds chaos. No one, apparently, has been put in charge of directing the boats or the boatmen, most of whom have forsaken their duty. Some are already returning without orders or permission, landing wherever convenient, leaving the boats where they touch the shore. Others are leaping into bateaux on their own, crossing over, then abandoning the craft to drift downriver. Many are swiftly taken prisoner by the British. Charles Askin, lying abed in the Hamilton house suffering from boils, hears that some of the militia have cheerfully given themselves up in the belief that they will be allowed to go home as the militia captured at Detroit were. When told they will be taken to Quebec, they are distressed. Askin believes that had they known of this very few would have put a foot on the Canadian shore.

As Chrystie struggles to collect the missing bateaux, his fellow commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Fenwick, in charge of the second assault wave, arrives only to learn that he cannot cross for lack of boats. Exposed to a spray of grape- and canister-shot, Fenwick herds his men back into the shelter of the ravine until he manages to secure enough craft to move the second wave out onto the river. The crossing is a disaster. Lieutenant John Ball of the 49th directs the fire of one of his little three-pounders, known as “grasshoppers,” against the bateaux. One is knocked out of the water with a loss of fifteen men. Three others, holding some eighty men, drift into a hollow just below the Hamilton house. All are slaughtered or taken prisoner, Fenwick among them. Terribly wounded in the eye, the right side, and the thigh, he counts nine additional bullet holes in his cloak.

None of the regular commanders has yet been able to cross the narrow Niagara. On the opposite shore under the sheltering bank, Solomon Van Rensselaer, growing weaker from his wounds, is attempting to rally his followers, still pinned down by the cannon fire from the gun in the redan and the muskets of Captain Dennis’s small force on the bank above. Captain John E. Wool, a young officer of the 13th Infantry, approaches with a plan. Unless something is done, and done quickly, he says, all will be prisoners. The key to victory or defeat is the gun in the redan. It must be seized. Its capture could signal a turning point in the battle that would relieve the attackers while the fire could be redirected, with dreadful effect, among the defenders. But how can it be silenced? A frontal attack is out of the question, a flanking attack impossible, for the heights are known to be unscalable from the river side. Or are they? Young Captain Wool has heard of a fisherman’s path upriver leading to the heights above the gun emplacement. He believes he can bring an attacking force

up the slopes and now asks Solomon Van Rensselaer’s permission to attempt the feat.

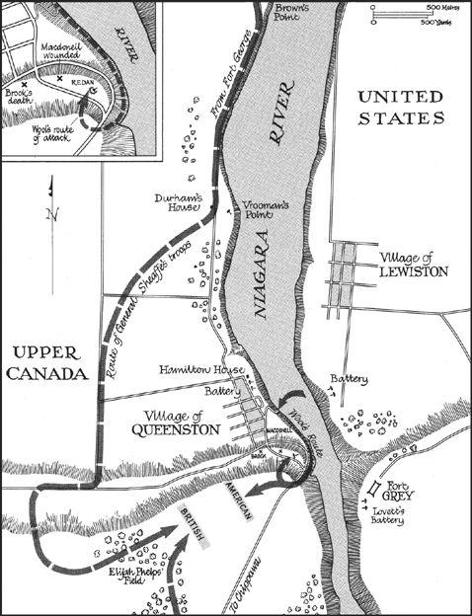

The Battle of Queenston Heights

Wool is twenty-three, a lithe, light youth of little experience but considerable ambition. One day he will be a general. The fact that he has been shot through the buttocks does not dampen his enthusiasm. With his bleeding commander’s permission, he sets off with sixty men and officers, moving undetected through a screen of bushes below the river bank. Solomon Van Rensselaer’s last order to him is to shoot the first man in the company who tries to turn tail. Then, as Wool departs, the Colonel slumps to the ground among a pile of dead and wounded, a borrowed greatcoat concealing the seriousness of his injuries from his wet and shivering force. Shortly afterwards he is evacuated.

Captain Wool, meanwhile, finds the path and gazes up at the heights rising almost vertically more than three hundred feet above him. Creased by gullies, blocked by projecting ledges of shale and sandstone, tangled with shrubs, vines, trees and roots clinging to the clefts, they look forbidding, but the Americans manage to claw their way to the crest.

Wool, buttocks smarting from his embarrassing wound, looks about. An empty plateau, bordered by maples and basswood, stretches before him. But where are the British? Their shelters are deserted. Below, to his right, half-hidden by a screen of yellowing foliage, he sees a flash of scarlet, realizes that the gun in the redan is guarded by the merest handful of regulars. Brock, who is a great reader of military history, must surely have studied Wolfe’s famous secret ascent to the Plains of Abraham, yet, like the vanquished Montcalm, he has been assured that the heights are safe. He has brought his men down to reinforce the village, an error that will cost him dear. Wool’s men, gazing down at the red-coated figures manning the big gun, cannot fail to see the tall officer with the cocked hat in their midst. It is the General himself. A few minutes later, when all are assembled, their young commander gives the order to charge.

AT FORT GEORGE, BROCK

has awakened in the dark to the distant booming of cannon. What is happening? Is it a feint near Queenston or a major attack? He is inclined to the former possibility, for he has anticipated Van Rensselaer’s original strategy and does not know of Smyth’s obstinacy. Brock is up in an instant, dressed, and on his grey horse Alfred, dashing out the main gate, waiting for no one, not even his two aides, who are themselves hurriedly pulling on their boots. Later someone will spread a story about Brock stopping for a stirrup cup of coffee from the hands of Sophia Shaw, a general’s daughter, said to be his fiancée. It is not convincing. On this dark morning, with the wind gusting sleet into his face and the southern sky lit by flashes of cannon, he will stop for nobody.

As he hurries through the mud toward Queenston, he encounters young Samuel Jarvis, a subaltern in his favourite militia unit, the York Volunteers. Jarvis, galloping so fast in the opposite direction that he cannot stop in time, finally reins his horse, wheels about, tells his general that the enemy has landed in force at the main Queenston dock. Jarvis’s mission ought not to be necessary because of Brock’s system of signal fires, but in the heat of battle nobody has remembered to light them.

Brock gallops on in the pre-dawn murk, past harvested grain fields, soft meadows, luxuriant orchards, the trees still heavy with fruit. The York Volunteers, stationed at Brown’s Point, are already moving toward Queenston. Brock dashes past, waving them on. A few minutes later his two aides also gallop by. John Beverley Robinson, marching with his company, recognizes John Macdonell, Brock’s provincial aide and his own senior in the York legal firm to which the young volunteer is articled. Brock has reason to be proud of the York militia, who answered his call to arms with alacrity, accompanied him on the embarkation to Amherstburg, were present at Detroit’s downfall, and are now here on the Niagara frontier after six hundred miles of travel by boat and on foot.

A few minutes after Brock passes, Robinson and his comrades encounter groups of American prisoners staggering toward Fort George under guard. The road is lined with groaning men suffering

from wounds of all descriptions, some, unable to walk, crawling toward nearby farmhouses, seeking shelter. It is the first time that these volunteers have actually witnessed the grisly by-products of battle, and the sight sickens them. But it also convinces them, wrongly, that the engagement is all but over.

Dawn is breaking, a few red streaks tinting the sullen storm clouds, a fog rising from the hissing river as Brock, spattered with mud from boots to collar, gallops through Queenston to the cheers of the men of his old regiment, the 49th. The village consists of about twenty scattered houses separated by orchards, small gardens, stone walls, snake fences. Above hangs the brooding escarpment, the margin of a prehistoric glacial lake. Brock does not slacken his pace but spurs Alfred up the incline to the redan, where eight gunners are sweating over their eighteen-pounder.

From this vantage point the General has an overview of the engagement. The panorama of Niagara stretches out below him—one of the world’s natural wonders now half-obscured by black musket and cannon smoke. Directly below he can see Captain Dennis’s small force pinning down the Americans crouching under the riverbank at the landing dock. Enemy shells are pouring into the village from John Lovett’s battery on the Lewiston heights, but Dennis is holding. A company of light infantry occupies the crest directly above the redan. Unable to see Wool’s men scaling the cliffs, Brock orders it down to reinforce Dennis. Across the swirling river, at the rear of the village of Lewiston, the General glimpses battalion upon battalion of American troops in reserve. On the American shore several regiments are preparing to embark. At last Brock realizes that this is no feint.

He instantly dispatches messages to Fort George and to Chippawa to the south asking for reinforcements. Some of the shells from the eighteen-pounder in the redan are exploding short of their target, and Brock tells one of the gunners to use a longer fuse. As he does so, the General hears a ragged cheer from the unguarded crest above and, looking up, sees Wool’s men charging down upon him, bayonets glittering in the wan light of dawn. He and the gunners have

time for one swift action: they hammer a ramrod into the touchhole of the eighteen-pounder and break it off, thus effectively spiking it. Then, leading Alfred by the neck reins, for he has no time to remount, the Commander-in-Chief and Administrator of Upper Canada scuttles ingloriously down the hillside with his men.

In an instant the odds have changed. Until Wool’s surprise attack, the British were in charge of the battle. Dennis had taken one hundred and fifty prisoners; the gun in the redan was playing havoc with the enemy; Brock’s forces controlled the heights. Now Dennis is retreating through the village and Wool’s band is being reinforced by a steady stream of Americans.

Brock takes shelter at the far end of the town in the garden of the Hamilton house. It would be prudent, perhaps, to wait for the reinforcements, but Brock is not prudent, not used to waiting. As he conceives it, hesitation will lose him the battle: once the Americans consolidate their position in the village and on the heights they will be almost impossible to dislodge.

It is this that spurs him to renewed action—the conviction that he must counterattack while the enemy is still off balance, before more Americans can cross the river and scale the heights. For Brock believes that whoever controls the heights controls Upper Canada: they dominate the river, could turn it into an American waterway; they cover the road to Fort Erie; possession of the high ground and the village will slice the thin British forces in two, give the Americans warm winter quarters, allow them to build up their invading army for the spring campaign. If the heights are lost the province is lost.

He has managed to rally some two hundred men from the 49th and the militia. “Follow me, boys,” he cries, as he wheels his horse back toward the foot of the ridge. He reaches a stone wall, takes cover behind it, dismounts. “Take a breath, boys,” he says; “you will need it in a few moments.” They give him a cheer for that.

He has stripped the village of its defenders, including Captain Dennis, bleeding from several wounds but still on his feet. He sends some men under Captain John Williams in a flanking movement to attack Wool’s left. Then he vaults the stone fence and, leading

Alfred by the bridle, heads up the slope at a fast pace, intent on retaking the gun in the redan.