Poison (36 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

“No English!” he finally said, pointing to his head, his ears, as though he was also deaf and mute. He pulled a scrap of paper from his pocket and scribbled a phone number on it. “Brother. My brother.”

“How are you?” asked the writer. “How are you feeling? That’s all I want to know.”

Dhillon pointed to his head again, shaking his head. “No. No English.”

All lies and jest,

Still a man hears

What he wants to hear

and disregards the rest.

Still a man hears

What he wants to hear

and disregards the rest.

—

Paul Simon, “The Boxer”

Paul Simon, “The Boxer”

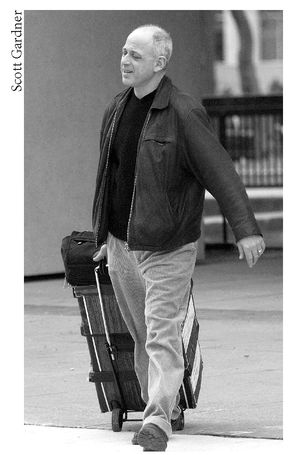

The Toronto defense lawyer with the close-cropped silver hair rose from his chair in the Hamilton courtroom, his physique trim and fit from the hours he spent swimming lengths. Dhillon had found a new defender.

Defense lawyer Russell Silverstein

“Respectfully, Your Honor, enough is enough,” Russell Silverstein said. His client, Sukhwinder Dhillon, sat behind him in the prisoner’s box. It was February 11, 2000. Pretrial motions in the Dhillon case were being heard before Ontario Court Justice C. Stephen Glithero. The Crown had previously recommended moving the entire trial to India to have access to witnesses without the cost of bringing them to Canada. But it had been seven months since the first overture was made to Indian officials, and there still had been no movement. It’s time to give up and begin the trial—start it now, here in Hamilton, said Silverstein, who had taken on the task of convincing a jury that Sukhwinder Dhillon was innocent.

Nearly 20 years earlier, Russell Silverstein had worked behind a piano for a living out west. He was 25 then, had already graduated from the University of Toronto and taken two years off to live in France and teach skiing. After returning to Canada, he enrolled in law school at McGill University, then gone to Columbia University in New York and practiced law in Manhattan. He took another year off in 1980,

as though trying to squeeze in a life before his career took over. He moved to Alberta, virtually lived on the slopes around Banff, paid his way by working as the piano man at a local bar. Then the music stopped and Russell Silverstein returned to the courtroom.

as though trying to squeeze in a life before his career took over. He moved to Alberta, virtually lived on the slopes around Banff, paid his way by working as the piano man at a local bar. Then the music stopped and Russell Silverstein returned to the courtroom.

Now he was 45 years old and the après-ski crowd gathered by the piano had been replaced by a clientele that included drug dealers, wife-beaters and, now, a possible serial killer. He was still working the room. His eyes were dark, deep blue or perhaps gray, their exact color impossible to determine even up close. He was not tall, but appeared athletic and nimble, walked with an assertive air. Today he stood before Judge Glithero on the issue of when and where the trial would begin. He gestured toward assistant Crown attorney Brent Bentham.

“I do appreciate that my friend,” he began with one lawyer’s customary reference to another, “can bring any witness he wants from anywhere in the world—if he can pull it off.”

Silverstein floated back to his seat in his black robe and white collar. He had got off another good line. In one quip he had pointed out the obvious—that Bentham was free to call his witnesses, while at the same time underscoring Bentham’s home-field advantage. Bentham, a.k.a. the Crown, had a bottomless pot of money to fly in witnesses from India or anywhere else. It wasn’t an option that he, Russell Silverstein, could possibly entertain.

Perhaps Judge Glithero, himself a former defense lawyer who certainly knew the disadvantages one faces when taking on the Crown, might consider Silverstein’s inherent underdog status when considering other matters as well. Silverstein had also succeeded in making a point with “if he can pull it off.” In other words, finding and bringing witnesses from India who would say what Bentham expected them to say, would be a chore indeed. Judge Glithero ruled that the trial would not go to India. It would begin in Hamilton, in September.

Seven months later, in September 2000, the trial of Sukhwinder Dhillon got under way at John Sopinka Courthouse in Hamilton

before a jury of seven men and five women. Russell Silverstein had handled many tough cases in his career, but this one gave him little room for optimism. The trial ahead would be a rat’s nest, if the interminable preliminary hearing had been any indication.

before a jury of seven men and five women. Russell Silverstein had handled many tough cases in his career, but this one gave him little room for optimism. The trial ahead would be a rat’s nest, if the interminable preliminary hearing had been any indication.

As for Dhillon, Silverstein would never talk to anyone about any discussions with his client, but observers in court sensed a level of exasperation in the lawyer. Dhillon brought newspaper clippings to court for Silverstein to review, seemed to badger the lawyer in their conversations. A defense lawyer must not present evidence he or she knows to be false or allow a client to commit perjury. But as a matter of ethics, the defender does not have to believe a client is innocent. Did Silverstein believe the professed innocence of his clients?

“I tend not to let myself disbelieve it.”

Russell Silverstein had made a career out of defending some nasty characters. That was okay. You don’t have to become friends with criminals, he would say. “You do your job.” What he thought of some of his clients did not matter. A year earlier, he had handled the Hamilton trial of Mark Laliberte, an accused killer. Silverstein won the case. When he heard he had been acquitted, Laliberte turned to the lawyer and said—“hissed,” said the story in

The Hamilton Spectator

—“What’s that mean? What’s that mean?” Silverstein hugged Laliberte. Laliberte burst into tears, yelling, “Oh Russell, I love you!” as he and his girlfriend, according to the

Spectator

, “whooped with joy.”

The Hamilton Spectator

—“What’s that mean? What’s that mean?” Silverstein hugged Laliberte. Laliberte burst into tears, yelling, “Oh Russell, I love you!” as he and his girlfriend, according to the

Spectator

, “whooped with joy.”

Silverstein chuckled about the newspaper account later, amused once again at the media’s simplistic take on the trial. Not that he was surprised. It’s rare, he thought, for the press to nail down the intricacies of a case.

Case after case, Silverstein saw the tears of victims’ families, heard the gasps of outrage in court as he defended his clients. He watched a widow weep when he called the death of her husband in a drug deal gone bad a “run-of-the-mill murder.” He knew some victims’ families would be upset. It’s sad. And it’s understandable. But emotion cannot deter a lawyer from doing what needs to be done. He saw himself as an avenger, taking on the Crown to keep it from treading upon the rights of others.

In Silverstein’s mind, an innocent person might end up in prison despite his efforts. He could live with that. But he could never accept the burden of prosecuting someone who was not guilty. That would be the hardest thing to handle. When he looked into the dark eyes of Sukhwinder Dhillon, did he see a serial killer or a man wrongly accused? It didn’t matter. It was not relevant. He was here to defend his client with all the legal skill he could muster. He had studied the evidence from every possible perspective. He knew all the facts of the case. The jury did not. But Silverstein also faced two top-drawer Crown lawyers. He was armed only with his understanding of law, his flair, and the assistance of a junior lawyer. Her name was Apple.

“Well, off to defend more criminals.” That was how the 28-year-old lawyer with the unusual name spoke. Fresh out of law school, Apple Newton-Smith was still finishing her bar admissions when she was recruited to start at the Toronto firm of Pinkofsky, Lockyer. Shortly after that she was brought on board to assist Russell Silverstein with a client he was defending. They lost that one, but Silverstein asked if she would work with him on another case—Dhillon. They might even win this one, he said.

As for her name, over the years it became simply routine.

“What’s your name?”

“Oh God, here we go again. Apple.”

“Sorry, what’s that? It sounded like you said your name was Apple.”

“I did. And did I mention my sister’s name is Rain?”

Apple Newton-Smith’s father had studied philosophy; her mother was a writer and teacher. While living in England they had two daughters and divorced in 1981 when Apple was nine. Apple returned to Toronto with her mom. Her name was—“apparently

”

—owing to a connection with Sir Isaac Newton. He was a distant relation, her father said. Another story had it that, while her mother was nine months pregnant, she read Ibsen’s

Peer Gynt

to the class she was teaching. There’s a line in it that says the soul should not be like an onion where you peel back layers, but like an apple, with a core. One of the students said the teacher should call her new baby Apple.

”

—owing to a connection with Sir Isaac Newton. He was a distant relation, her father said. Another story had it that, while her mother was nine months pregnant, she read Ibsen’s

Peer Gynt

to the class she was teaching. There’s a line in it that says the soul should not be like an onion where you peel back layers, but like an apple, with a core. One of the students said the teacher should call her new baby Apple.

Apple eventually majored in English and philosophy at McGill. And she started doing legal work with young offenders. Defending those charged with breaking the law seemed a practical application of philosophy, arguing about rights. Defending the wrongly accused—even better. What she thought of Dhillon, the wife-beater, bigamist, and alleged serial killer was irrelevant. He is the client. You prepare him for trial.

“It’s not as if you have coffee with the guy. You do your job.”

CHAPTER 20

LIES ALL AROUND

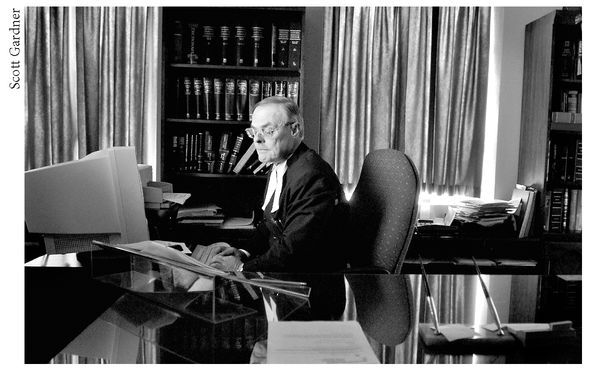

It had been in April 1999 when Superior Court Justice C. Stephen Glithero took the phone call in his Kitchener office. The regional senior justice had a new assignment for him. A double-murder jury trial, accused named Dhillon, Sukhwinder Singh. The prelim alone had been nearly a year.

“It’s going to be a long trial,” he predicted.

Glithero’s disdain for routine cases was well known. He did not shrink from challenges, he welcomed them. It had been back in 1967, September, the first day of the semester, when 21-year-old Steve Glithero stood in the doorway of the law school dean at the University of Western Ontario in London. Steve had applied to get into law school there and had been rejected. He had received letters of acceptance from three other law schools, but Western was where he wanted to go. His wife had a job in London and he liked the city. So he asked the receptionist if he could meet the dean.

“I don’t think you understand,” the dean said. “You didn’t get in. We have refused your application. Good luck to you.”

Steve Glithero left. The dean’s rejection was merely the opening argument. He went back to the office the next day.

“You really don’t get it, do you?” the dean said. “You were not accepted. Now please, I have work to do.”

Two days later, he made his pitch once more. Perhaps the dean would simply get sick of him and give in, he reflected. Or call the police.

“Oh, all right,” the dean finally said, capitulating. “Just get in class.”

Fast-forward 25 years to a late July day. Steve Glithero is a crack defense lawyer in Cambridge and Kitchener, but on this day he is gliding in his boat on Georgian Bay, wind filling the sail. He was alone on the boat, as always. There was no phone, no fax machine. He was gloriously out of touch. He rounded a point and saw a friend waving frantically at him. What was going on? Someone back at the office had called the friend. If you see Steve, get him to a phone. This was important. He docked and went to the cottage. Then he returned the phone call to federal Justice Minister Kim

Campbell in Ottawa. He was no longer Steve Glithero. He was C. Stephen Glithero. Judge.

Campbell in Ottawa. He was no longer Steve Glithero. He was C. Stephen Glithero. Judge.

Superior Court Justice C. Stephen Glithero

Other books

Shrinking Violet (Colors #2) by Jessica Prince

Endangered Species by Barbara Block

In the Sea There are Crocodiles by Fabio Geda

Cry of the Wolf by Dianna Hardy

Midnight Reign by Chris Marie Green

A Free Choice (Ganymede Quartet Book 4.5) by Glass, Darrah

Cloak of Darkness by Helen MacInnes

The Kabbalist by Katz, Yoram

Closed Circles (Sandhamn Murders Book 2) by Sten, Viveca

Reclaiming His Pregnant Widow by Tessa Radley