Pompeii (13 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

In many ways the schematic plan of the Pompeian street system, so often reproduced, is misleading. For, just as today many motorists find that a simple map of an unfamiliar town may fail to warn them of the pedestrianised precincts or the one-way streets, so this plan tends to conceal the actual pattern of movement around ancient Pompeii. The picture of free circulation implied by the diagram is contradicted by the evidence on the ground. Here too we find traffic-free zones and, it seems, some control of the direction of traffic flow. Recent work – looking very carefully again at the ruts and stepping stones – has even suggested that we can begin to reconstruct the Pompeian one-way street system.

23. Traffic barriers old and new. These three stone blocks emphasize the ban on traffic travelling between the Forum, which lies behind us, and the Via dell’Abbondanza, which stretches into the distance. On the left, the modern site authorities use plastic fencing to keep visitors from buildings under restoration.

The streets of Pompeii could be closed to wheeled transport by simple devices: by large stone bollards fixed in the roadway, by the placing of fountains or other obstructions across the traffic path, or by steps or other changes of level that were impassable to carts. Every one of these was used to ensure that, at least in its final phases, the Pompeian Forum was a pedestrian area. We should put out of our minds any fanciful reconstruction of the central piazza criss-crossed by chariots and carts. Each entry point to the Forum was blocked to wheeled traffic: at the Via dell’Abbondanza by three bollards and a high kerb, at the south-east entrance by a strategically positioned water fountain, and so on. Interestingly, it was not only wheeled transport whose access to the Forum could be controlled. At every entrance point, fittings for some form of barrier or gate can still be made out, closing the area off even to those on foot. The precise purpose of these gates is unknown. Perhaps they were to close the area at night (though they would have to have been formidable barriers to put off a determined vandal). Perhaps, as one recent suggestion has it, they were used when elections were taking place in the Forum, as a means of controlling entrance to the elections and of excluding those without the right to vote.

A pedestrianised central square is one thing. But the Pompeian traffic schemes went beyond that. For the Via dell’Abbondanza is also blocked to wheeled transport almost 300 metres further along, at its junction with the Via Stabiana, where an abrupt drop of more than 30 centimetres makes it impassable to even the most sturdy cart. This stretch of the street between the Forum and Via Stabiana was not completely traffic-free, as it could be accessed from some of the intersections to north and south. But it obviously did not provide the easy through-route across the town that the map at first sight suggests. Its comparatively shallow cart ruts also indicate that it did not carry a large volume of traffic (although one sceptic has argued that the relative absence of ruts is equally well explained by the road having been repaved not long before 79). There are other signs too that this piece of road was in some way special. Part of it, the section in front of the Stabian Baths, is unusually wide: in effect it forms a small triangular piazza at the entrance to the Baths. And it was, of course, this stretch of road where, unlike the section to the east, we noted the almost complete absence of bars and taverns.

Exactly what was ‘special’ about it is harder to say. But one good guess is that it has something to do with the position of this stretch of the Via dell’Abbondanza between the theatres and ancient Temple of Minerva and Hercules to the south and the main Forum, with its temples and other public buildings. Little-used for day-to-day traffic, and not the main transport artery that most people now imagine, perhaps it formed part of a processional route from one civic centre to the other, from Forum to Theatre, or from Theatre to Temple of Jupiter? Processions were a staple of public and religious life in the Roman world: a means of celebrating the gods, parading divine images and sacred symbols before the people, honouring the city and its leaders. The details and calendar of these ceremonies at Pompeii are lost to us, but we maybe have the traces of one favoured route.

There are, however, still more road blockings along the Via dell’Abbondanza. Moving from the Via Stabiana towards the eastern gate (the Sarno Gate, so called after the river which flows on this side of the town), most of the road intersections to the south and some to the north are either completely impassable to carts or steeply ramped but still – as the ruts running over them make clear – accessible to wheeled transport. Part of the purpose of this must have been traffic control, but the other part was, once again, the control of water. The Via dell’Abbondanza runs across the town about two thirds of the way down the slope on which the city rests: the streets below it must have been particularly liable to nuisance and damage by the torrents flowing down from above. Hence these ramps and blockings, which would have prevented much of that water flowing into the lower region of the town, directing it instead into the Via dell’Abbondanza and channelling it out at the Sarno Gate. Part of this street may have been a ‘processional way’; another part was certainly a major drain.

Pompeian traffic was then reduced or, in modern terms, ‘calmed’ by the creation of cul-de-sacs, and other kinds of road block. But there remains the more general problem of narrow streets and what would happen if two carts should meet in those many roads which were wide enough only for one. Needless to say, reversing a cart drawn by a pair of mules, down a road impeded by stepping stones, would have been an impossible feat. So how did the ancient Pompeians avoid repeated stand-offs, between carts meeting head-to-head? How did they prevent a narrow street being reduced to an impasse?

One possible answer is a combination of loudly ringing bells, shouts and boys sent ahead to ensure the path was clear. The horse trappings found with the cart in the House of the Menander certainly included some harness bells which would have made a distinct jingle to warn of approaching traffic. But there are signs that a system of one-way streets was in operation in the town, to keep the carts moving freely. The evidence for this comes from some of the most painstaking efforts in Pompeian archaeology over the last decade or so, and from the clever idea that the precise pattern of the street ruts, and the exact position of the marks produced by carts colliding with the stepping stones, or grazing the kerb at corners, could tell you which way the ancient traffic was moving along a particular stretch of road.

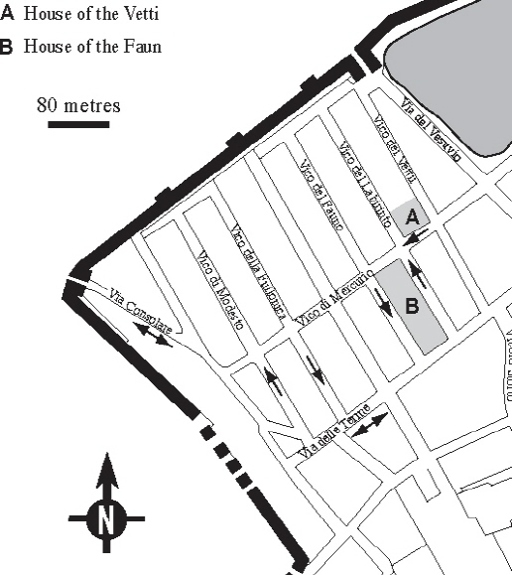

One of the most convincing examples of this occurs in the north-west part of the town, on the way from the Herculaneum Gate to the Forum, where the road we now know as the Via Consolare meets the narrow Vico di Mercurio (Fig. 5). Here the combination of the collision marks on the south-west side of the stepping stone in the middle of the Vico di Mercurio and the precise pattern of grinding on the kerbstone to the north indicates that traffic was coming along the Vico di Mercurio from the east and mostly turning north when it met the two-way Via Consolare at the junction. The Vico di Mercurio was, in other words, a one-way street, running east to west. Traffic coming down the Via Consolare, wanting to take a left turn towards the east, would have to wait until it reached the broad Via delle Terme – which was a two-way street. Similar evidence has been taken to suggest that there are clear distinctions on the north–south streets in the area too: the Vico di Modesto and Vico del Labirinto carrying northbound traffic, the Vico della Fullonica and Vico del Fauno southbound.

Figure 5

. The road system in the north-west of Pompeii: the conjectural lay-out of one-way streets.

Whether the degree of systematisation is quite so rigid as the most enthusiastic modern archaeologists would have us believe, I am rather doubtful. When they write, on the basis of apparently conflicting evidence in some places, that the Vico di Mercurio had originally carried traffic in the other direction and that it ‘underwent a reversal from an eastbound to a westbound route’, it is hard to imagine how such a reversal would have been brought about. Who decided? And how would they have enforced the decision? Ancient cities had no traffic police or transport department. Nor have we found any trace of traffic signs, in a town where there are plenty of other kinds of public notices. Nonetheless, there seems little doubt that there was a pattern of traffic direction generally observed, even if only enforced by common usage. By following the agreed routes, the cart drivers of Pompeii had a better chance of avoiding a complete jam than if they merely rang their bells loudly and hoped that nothing was coming round the corner.

Pavements: public and private

The pavement was the borderland between the public world of the street and the more private world behind the thresholds of houses and shops – a ‘liminal zone’, as anthropologists would call it, between outside and inside. At busy taverns, facing onto the street, the pavement provided overspill space for customers who ‘propped up the bar’, or waited for food and drink to take away. For drivers of animals, making deliveries or simply taking a break, and for visitors arriving on horseback at large houses, it also offered convenient tethering posts, or rather tethering

holes

. All over the city, in front of bakeries, workshops, taverns and stores, as well as at the entrance to private residences, you can still find small holes drilled through the very edge of the pavement, hundreds of them altogether.

Puzzling to archaeologists, these were once thought to be the fixing points for sun blinds to provide shade for the open premises behind – an idea drawn in part from the practice in historical Naples of draping awnings over shop fronts. If this were the case, it would have turned the pavements, on sunny days at least, into a forest of fabric, and dark, makeshift tunnels between shop and kerbside. Maybe that is how it was. But a much simpler idea, and one that fits better with the distribution of these holes, is to think of them as places to tie up animals (and if not here, then where else?). Even this would hint at another awkward picture of Pompeian street life: the delivery man’s donkeys, tethered to the edge of the narrow street, being forced to join the pedestrians on the pavement in order to clear the way for a cart squeezing its way through.

Awnings or not, the sun must sometimes have made the city’s pavements unpleasantly hot, even if two-storey houses on both sides of the road (especially where the upper storeys were built out at an overhang) did offer more shade than weary visitors find in the ruined streets today. Unsurprisingly some householders took remedial action. Across the frontage of some of the larger residences canopies once jutted out from the façade, providing extra shade not only for those entering the property, but for any passer-by. Stone benches were sometimes added on either side of the front door, also taking advantage of the shade provided. Exactly who we are to imagine sitting on these depends on our view of the mentality of the Pompeian elite. They may have been installed, partly at least, as an act of generosity to the local community: a resting place for one and all. They may, however, have been intended solely for visitors waiting to be admitted to the house itself. In fact, it’s not at all difficult to picture the porter emerging from behind those vast front doors to chase off the riff-raff who had chosen to sit down there uninvited.

Walking around the town today, we can spot all kinds of other examples of private property, and its amenities, encroaching onto the pavement. Some owners turned the pavement in front of their houses into a ramp, to allow carts easy access inside. That, at least, was how the landlord of one of the inns or lodging houses near the Herculaneum Gate catered for the needs of his guests – allowing them easily to bring their carts, belongings and merchandise into the security of the inner court. Others used it to construct themselves even more monumental entrances than usual. One large property at the far east end of the Via dell’Abbondanza, now known as the Estate (

Praedia

) of Julia Felix, after the woman who once owned it, was given a pretentious stepped walkway, built right over the pavement. Further up the same street towards the Forum, the front door of the House of Epidius Rufus opened onto an extra terrace, more than a metre high, which was set on top of the already elevated pavement – giving the house a lofty remoteness from the life of the street beneath. With a more practical aim in view, the owners of the House of the Vettii inserted a series of bollards into the street along the side wall of their mansion. The roadway was narrow and there was no pavement to act as a barrier between house and road. They must have been worried about the damage that might be done by passing carts, carelessly driven.