Pompeii (14 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

Some of these encroachments may have received permission from the town council or the local aediles. A handful of painted notices found on the outside of the Amphitheatre suggest that it was the aediles who authorised the street vendors plying their trade underneath the monument’s arches, and assigned their pitches: ‘By permission of the aediles. Licensed to Caius Aninius Fortunatus’ etc., as the faint and fragmentary Latin seems to say. Maybe the better-off made a similar application to the authorities. Or maybe they simply assumed the right to do much as they pleased with the pavements in front of their houses.

The householders might have had good reason to make that assumption – to judge from some tell-tale traces in the pavements themselves. Most city pavements, ancient or modern, are much less homogeneous than the casual passer-by tends to recognise. Their surfaces have been laid at different periods; they have been repaired in patches, often with not much care to make a match with the surrounding material. This is as true of Pompeii as it is of modern London or New York. Yet in Pompeii a closer look reveals rather more systematic discrepancies. In some streets the pavements seem originally to have been laid in different materials (volcanic rock, limestone, tufa) – and in stretches corresponding to the frontages of houses. In places there are even blocks set into the pavement marking the division between one property (and its pavement) and the next.

The conclusion is obvious. Even though they must have been planned by some central city authority, their width and height fixed to an agreed standard, some of these pavements were paid for on a private basis, by an individual householder, or by a group of them clubbing together – the choice of material to be used left up to those who were footing the bill. It is logical to imagine that their upkeep was similarly privatised. That idea is supported by a surviving Roman law (inscribed on bronze and found in the far south of Italy) which gives the regulations for, amongst other things, the upkeep of roads and pavements in the city of Rome itself. The basic principle was that each householder was responsible for the pavement frontage of his own property, and if he did not maintain it properly the aediles could themselves contract the maintenance work out and then recover the cost from the defaulter. Interestingly, an additional obligation on the householder at Rome was to make sure that water did not collect so as to inconvenience people in the street. It was not only Pompeii that had trouble with overspills.

The people in the streets

So far the people in the Pompeian streets have been rather shadowy figures. We have spotted the traces they left behind them: the scrawls on the walls, the hands on the fountains, the scratches and scrapes left by the carts on the kerbsides. But we have not seen the men, women and children face to face; we have not caught them at their daily business.

We can in fact get one step closer to them, thanks to an extraordinary series of paintings found in the Estate of Julia Felix. At the time of the eruption this large property, with its imposing entrance that we have already noted, covered the whole of what had once been two city blocks not far from the Amphitheatre. It included a number of different units: a privately run, commercial bathing establishment, a number of rental apartments, shops, bars and dining rooms, a large orchard and a medium-sized private house. One large room in this establishment (an inner courtyard or atrium, just over 9 metres by 6) was decorated with a painted frieze, two and a half metres above the ground, apparently showing scenes of life in the Pompeian Forum. This was uncovered by eighteenth-century excavators who removed to the museum about 11 metres of it, in small, broken sections, leaving just a couple of fragments on the wall. What happened to the rest, or even how much more there was (it’s only an assumption that it once extended around the whole room), we do not know. But it is a likely guess that much of it fell victim to the robust excavation techniques of the time.

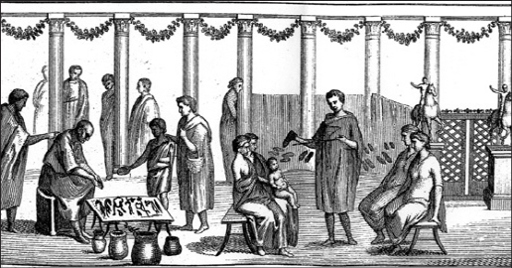

24. This eighteenth-century engraving preserves details of the now faded painted scenes of life in the Forum. Behind the traders it is interesting to see how the bare columns of the Forum colonnade might have appeared in the ancient world itself: decorated with hanging festoons and used to support temporary partitions and gates.

The paintings are now badly faded. Even so, they offer as vivid a picture as we could hope for of life on the Pompeian streets – particularly when combined with engravings of them made soon after they were found which help to throw light on some of the murkier sections. They are not, of course, strictly realistic. The background architecture is a rather rough-and-ready version of the two-storey Forum colonnade (though the position of the statues and their relationship to the columns matches up quite closely to the remains on the ground). The intense bustle of activity at every point almost certainly goes well beyond what would be found even on the busiest market day. This is not daily life, but an imaginative re-creation of it. It is a Pompeian street scene in the mind’s eye of a Pompeian painter: beggars, hucksters, schoolkids, fast food, ladies out shopping ...

In one of the most detailed sections (Ill. 24) we get a glimpse of a couple of street traders at work, with varying degrees of enterprise. On the left of the scene is a dozy ironmonger. His table is set out with what look like hammers and pincers, which he has brought to his stall in the baskets lined up at the front (or are they metal jars for sale?). He has a couple of customers: a young boy with an older man, shopping basket on his arm. A sale is in the offing. But it looks as if the ironmonger has nodded off, and needs a wake-up call from the man behind him. On the right, a shoemaker in a bright red tunic is doing much more active trade, pitching his wares to a group of four ladies and a baby, who sit on the benches he has provided for his customers. Behind him, his range of shoes are on show in a way that baffled our eighteenth-century copyist (who depicts them floating in mid-air) and is now impossible to make out on the original. Most likely he has fixed up some display stands, propped against the columns behind. These run all along the back of the scene, festoons hanging between them. On the right, behind a couple of diminutive statues of men on horseback (in this position, probably local bigwigs – emperors would be given a more prominent setting), the space between two columns is closed by a gate. All of this is a good antidote to the austere, uncluttered, lifeless appearance of the colonnade today.

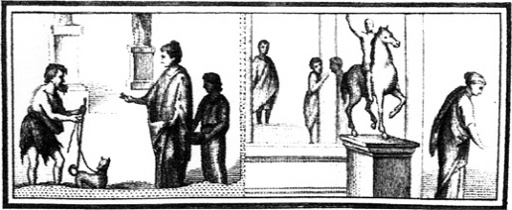

25. Buying and selling. On the left a couple of women are negotiating for the sale of some cloth. On the right a man, who has come shopping with his son, is buying a pan.

26. While a lady gives a handout to a scruffy beggar (plus dog), in the background a pair of children play peek-a-boo around a column. In the foreground is one of the many statues that stood around the Forum.

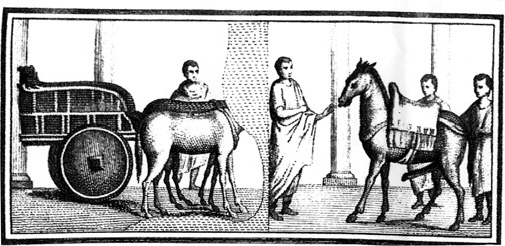

27. Methods of transport. On the right a donkey or mule is laden with a heavy saddle (note there are no stirrups). On the left is the kind of cart that once trundled the streets of the town.

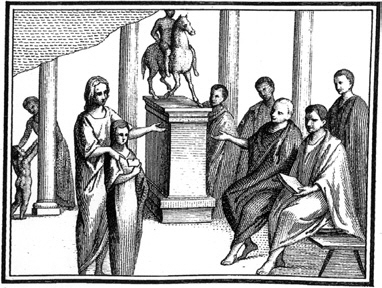

28. A couple of men sitting on a bench under the Forum colonnade are perhaps adjudicating some legal case. Three men behind watch the proceedings with some care, but in the background is a more domestic scene: a Pompeian toddler asks his mother or carer to pick him up.

We are given plenty of other vignettes of buying and selling. In one section (Ill. 25), women negotiate with salesmen over pieces of cloth; a man (one of the relatively few characters here to be dressed in a toga – although it is red rather than white) chooses a metal saucepan, while his young son carries the shopping basket; and a baker serves a pair of men with what appears to be a basket of rolls. Elsewhere, in the shadow of an arch, a greengrocer has a magnificent collection of figs for sale, while a food vendor has rigged up a brazier and is busy selling hot drinks or snacks. But it is not only commercial activities that the painter has shown. There is a touch of low life (Ill. 26): an elegant lady, plus slave or child, appears to be helping the homeless, by offering cash to a very ragged beggar with a dog. And there are several glimpses of the Pompeian traffic in the shape of mules and carts (Ill. 27). Given that, as we have seen, the Forum was a pedestrianised area, is the cart artistic licence? Or were there ways – ramps over the steps perhaps – of allowing wheeled transport into the area on some occasions, or at certain times?

Local politics too plays a significant part in this vision of Pompeian life. In one scene (Plate 7), some men are reading a long public notice, written on a board or scroll, which has been fixed across the bases of three more equestrian statues (this time, perhaps members of the imperial house, shown as military heroes). Elsewhere it looks as if some kind of legal case is going on (Ill. 28). A couple of men, dressed in togas, are seated, concentrating hard as they are addressed by a standing figure – often identified as a woman, but the traces are too ambiguous to be sure of the sex. He, or she, is making a particular point, gesturing to a tablet held by a young girl who stands in front. Whether, as some have thought, this girl is meant to be the subject of the case (an issue of guardianship perhaps), or whether she is merely a convenient prop for the evidence in question, it is impossible to tell. Behind looms another of those ubiquitous equestrian statues.