Prime Time (26 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

day you mean one more.

MARGE PIERCY,

excerpted from “The low road”

in

The Moon Is Always Female

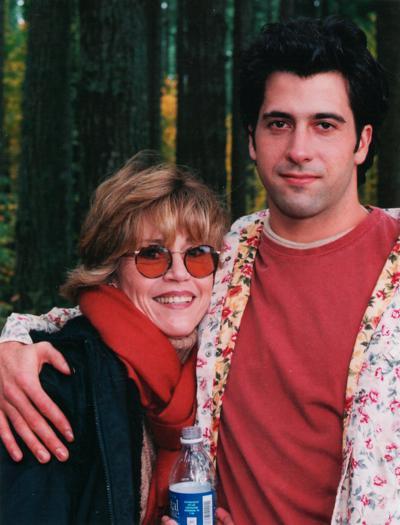

With son Troy on his

Bandits

set

.

Saying “We” and Knowing Who We Mean

It is May 2008. We are in my Atlanta loft having dinner. My brother, Peter, is next to me. He’s flown in from Los Angeles, as have my son, Troy, and daughter-in-law, Simone, along with Bridget Fonda, Peter’s daughter, and her three-year-old son, Oliver, who is sitting on the floor playing with my grandchildren’s toys while they—nine-year-old Malcolm and five-year-old Viva—throw pillows down from the second-floor balcony to build a fort. Their mother, my daughter, Vanessa, is at the table, calm as usual in the midst of raucous children. Odd as it may appear to some, Ted Turner is sitting at the far end of the table with Elizabeth, one of his girlfriends, whom I like. This evening represents a long overdue coming together for my family, and I cannot help but be emotional as I make a toast to love, friendship, and continuity.

The hook that got us all here is the thirteenth annual fund-raiser for my nonprofit, the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention; the theme this year is “Three Generations of Fondas in Film.” Tomorrow the family will be interviewed onstage about our careers by Robert Osborne, the host of Turner Classic Movies, and the evening will end with an homage to Henry Fonda, our father and grandfather.

Malcolm and Viva, all dressed up to go out. Clearly Viva is happier about the dress-up part than Malcolm.

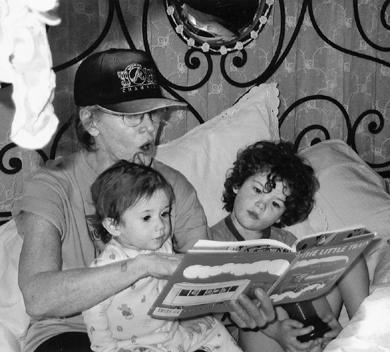

Reading to my grandchildren, Malcolm and Viva, around 2005.

Me with brother Peter, niece Bridget, and son Troy at the Fonda Family Film Festival in Atlanta in 2007.

But the payoff for me is this gathering of the clan, some members of which, because of festering family “issues,” have not been in meaningful contact for more than two years. It was my seventieth birthday last year that launched me into shuttle diplomacy and a commitment to change the situation. I wanted to say “we” and know who I meant. I was tired of not being sure that it included kin. I hated that I hadn’t met Peter’s daughter’s son, my grandnephew, that he didn’t know his second cousins, my grandchildren, that I’d never had a meaningful conversation with Bridget about her five-year absence from film or tried to get to the bottom of what had been going on with Peter. It felt right that a clan gathering include Ted. Over the decade that he and I were together, his children and my children had grown close despite the odd-coupling of the two culturally disparate families—mine inclined to tolerance for tattoos, hip-hop, and a discreet earring, his to “yes ma’am, no sir” manners and following military academy rules. Since our divorce, Ted and I have shared the desire to keep it all as connected as possible. So he was excited when he heard we were coming together and asked to be invited, just as he was invited to my son’s wedding.

I had experienced the pain of losing family before there had been forgiveness and closure. Not wanting this to happen again motivated me to circle the wagons of love while there was still time. When the event that brought us together was over and I sent the West Coasters on their way, we all knew that we would stay connected—and we have.

I’ve come a long way since the days when the Lone Ranger was my role model. This isn’t surprising, considering that the template for the governing ethic of my world growing up was the rugged individualism of my father. It was partly a generational thing, partly his midwestern staunchness; but mostly, my father was reflecting core western values: A fully mature human being is independent and autonomous.

Don’t need anybody. Be tough and self-reliant. Needing is a weakness.

This cultural scaffolding has posed a dilemma for women. We tend not to be rugged individualists. We build networks of friends upon whom we rely for relational sustenance, to boost our spirits, and to keep our secrets. Because of this, women had been considered less mature, irrational, and even pathological in comparison with men.

Wanting to avoid these labels, I tried to be more like men, not recognizing my emotional needs, much less expressing them, and always holding a part of myself in reserve. Men seemed to be where the action was, and being insular like them felt safer. A friend of the French film director Roger Vadim, my first husband, once said of me, “She’s great. Not like most women, more like us.” At the time, I viewed this as a compliment. This independence made me very strong. It also made me very weak, although it took me some sixty years to understand the nature of the dichotomy.

The strength part allowed me to embody that old family motto:

Perseverate.

It let me keep moving despite everything, and experience three marriages to challenging men without getting run over. The weakness part prevented me from experiencing that deep pocket of intimate love—surely the most precious one—which exposes a person to vulnerability. All of which brings me to the Marge Piercy poem that opens this chapter.

I love this poem. It takes me back to the early 1970s, when I first became an activist. I was newly into my Second Act, freshly arrived back home from France, wanting to throw myself into the movement to end the Vietnam War and, on a deeper, barely perceived level, feel that there was meaning to my existence.

At the time, I noticed how different the women activists were from any people I could ever remember meeting. Just being in their presence felt like a haven. I didn’t know I was missing community until I met up with it for the first time. These were the early years of the new women’s movement, and the feminists I spent time with in the trenches were intentional in living their values of noncompetitiveness and sisterhood—and it was powerful.

I remember vividly when I first witnessed this in action. It happened at a GI coffeehouse in 1971. Run by antiwar activists, these coffeehouses were meeting places that were springing up outside major military bases around the country. A few of the men on the staff had gone ahead on their own and passed out leaflets to GIs without consulting the women staffers. One of the women found out and protested. The men put her down for making a fuss, since they knew the contents of the leaflets would have been approved anyway. The other women on staff stood by her: “If we’re trying to model democracy within the staff, then process matters. You’re not entitled to take us for granted.” I’d always sided with the men—the winning side, or so I’d thought—so this brought me up short.

By now I’ve grown accustomed to these acts of solidarity among women, but witnessing the power and beauty of it when it was still so startlingly new to me burned away my individualistic dross and allowed the pure gold of friendships to enrich and cushion me. Today, as the separate skeins of my life weave themselves into its final fabric, I want, above all else, for there to be many threads of love shimmering through. I often think how different, how frightening, aging would be for me had this not happened. I know that I can lose everything but that my friendships with women, together with my family, will always be there, no matter what.

Most of my friends are younger than I am, some by more than twenty years. They are creative people, spiritual people, businesspeople, and activists for social change. We have one another’s backs. When I am down I can talk to them, and their understanding, advice, and encouragement lift me. I try to do the same in return.

When I had hip replacement surgery several years ago, Eve Ensler was at my bedside, massaging my feet, as I surfaced through the haze of anesthesia. “Why are you here?” I asked, unused to being tended to and knowing all too well how unimaginably busy Eve was. “Because I’m your friend,” she laughed. “Of course I’m here. I want to take care of you.” I allowed myself to relax into this caring, but it wasn’t easy. To paraphrase Ursula Le Guin, I am a slow unlearner, but oh my, how I love my unteachers.

1

Eve Ensler in 2011.

PAUL ALLEN