Prime Time (30 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

In an article in the

New York Times,

Tara Parker-Pope reported the results of a study done in 2000 in Vermont after same-sex civil unions were legalized in the state. She noted that “same sex relationships, whether between men or women, were far more egalitarian than heterosexual ones.… While gay and lesbian couples had about the same rate of conflict as the heterosexual ones, they appeared to have more relationship satisfaction, suggesting that the inequality of opposite-sex relationships can take a toll.” Apparently, same-sex couples resolve their conflicts better. In the same article, Robert W. Levenson, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, is quoted as saying, “When they got into these really negative interactions, gay and lesbian couples were able to do things like use humor and affection instead of just exploding.”

7

These findings seem to confirm what I have been saying: that democracy within a relationship is key to the long-term happiness of the couple.

Individuation and androgenization were present in the longterm relationships whose partners I interviewed. You may think, judging from previous chapters, that I am cavalier on the subject of long-term commitment, whether in marriage or in loving partnerships. I am actually a true believer. I regret that I’ve not stayed married to one man for the long haul, but I’ve made some fairly deep transitions over the course of my life so far, and the men I was with either didn’t want to transition with me, or couldn’t, or were transitioning in a different direction. As Lillian Hellman once said, “People change and forget to tell each other.”

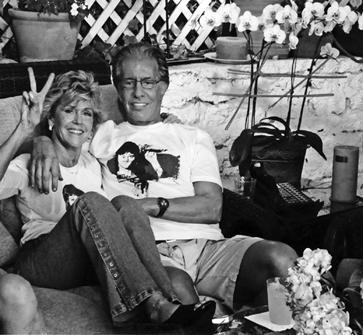

Richard and me in 2009.

Then again, on my side, I think that up until my sixties I was challenged in the intimacy department because I lacked the individuation and androgenization factors. I knew that I risked dying without ever really experiencing the kind of deeply intimate relationship with a man that I have experienced with women. That would be my big regret. (I am speaking not of sex but of emotional intimacy!) So I’ve worked on myself. Writing my memoirs was part of it. I am in a relationship now that has the potential I seek. I cannot know for sure. It’s only been sixteen months, as of this writing. I am with a man who is not at all in a spiritual transition. We are actually very different. But he isn’t afraid of intimacy, and I have become a freestanding adult, and maybe, just maybe, this relationship can be a crucible in which I get to heal myself even further.

8

He’s younger than I by five years, but old enough to feel the need, as I do, of doing all he can to forge something real and—well, not long-lasting; it’s not like there’s all that much time left! Something real and meaningful is what we’re after. We’ve both had a lot of experience with relationships. We’ve both either chosen inappropriately or lacked the know-how to work through what was wrong and get it to work. Time is running out … there’s twenty years or a bit more at best.

It takes being intentional to keep passionate intimacy alive and well. For example, romantic time needs to be scheduled. So does talking things through. In the past, I would often stuff down my feelings about things my partner did that I didn’t like, because I was scared he’d leave, and then where would I be? Now when something my partner has done upsets me, I schedule a sit-down to talk about it … or he forces us to talk about it when he feels something’s not right. Invariably we come away from these talks stronger than before. I’ve told him what I like about him and what I have problems with. I am realistic enough to know that there are things he can’t change and things I’m too old to want to fix. Like Suzanna, I’m tired of trying to fix a mate. (Not that I don’t bite my tongue sometimes!) But I feel that at this point, if he wants this to work enough, he will make an effort to do certain things differently if they are deal breakers for me, and I am prepared to do the same for him.

I sometimes feel guilty because I want so much in a relationship. In my grandparents’ day, couples seemed to accept that after a while romance would be replaced by companionship. But back then companionship didn’t get that old, because

people

didn’t get that old. They died. Instead of getting bored and divorcing, people died and the remaining spouse remarried—or not. Terrence Real, in his wonderful book

The New Rules of Marriage,

suggests that the change in the nature of what was desired in long-term relationships really began in the 1970s with the women’s movement. Women entered the workplace, became more financially independent, attended consciousness-raising groups, gained a modicum of political power, and discovered in the process that when they brought their innate gifts of empathy and intimacy into their workplaces and relationships, healing would happen, problems would be solved—differently, more easily—and it felt good. Who doesn’t want to feel good? Real says, “We have grafted onto the companionship marriage of the previous century the expectations and mores of a lover relationship—the kind of passion, attention, and emotional closeness that we most commonly associate with youth, and with the early stages of a relationship.”

9

The five tactics he suggests for cultivating this kind of relationship are:

- Reclaim romantic space. (This is easier to do now, when the children have left home and there is more time and job flexibility.)

- Tell the truth. (This is easier for a woman to do if she has confidence and individuation.)

- Cultivate sharing. (Intellectually, emotionally, physically, sexually, and spiritually.)

- Cherish your partner. (Develop your “lover energy”—the energy that goes into loving. Don’t just feel it; act on it.)

- Become partners in health. (Share a commitment to relational practice. As I have said, an intimate, passionate, long-term relationship doesn’t happen spontaneously. It requires commitment to engaging in relational practice.)

10

Sociologists say that marriage seems to encourage stability, a sense of obligation to the other, a barrier to loneliness, more financial security because of pooled resources, and better health. “Married people are less likely to get pneumonia, have surgery, develop cancer or have heart attacks. A group of Swedish researchers has found that being married or co-habitating at midlife is associated with lower risk for dementia,” notes Tara Parker-Pope, who writes the

Well

blog for the

New York Times.

Parker-Pope goes on to say, however, that a bad, stressful marriage can leave a person far worse off than if they’d never married at all. In fact, it can be “as bad for the heart as a regular smoking habit.”

11

Obviously, though, marriage is not for everyone. If you have found that there is no room in your marriage for a fully awakened, authentic you, it may be far healthier to leave than to swallow your unhappiness and shrink yourself back into a half life. If along the way you’ve stopped facing your real feelings and needs, stopped being truthful to yourself, you will inevitably go numb—the best, most potentially vital parts of you will shut off. You will also be angry, although this, too, may be covered over. Studies show that a bad marriage, with its potentially toxic stress, is especially bad for the wife’s health. A fifteen-year Oregon study cited by Suzanne Braun Levine in

Inventing the Rest of Our Lives

found that “having unequal decision-making power was associated with higher health risks for women, but not for men, perhaps,” Levine conjectures, “because women don’t have the other opportunities to exercise power that men traditionally do. Powerlessness is a major contributor to stress and depression.”

12

Marriage brings more benefits to men than it does to women, since women do the lion’s share of the emotional nurturing, child rearing, housekeeping, and meal cooking—which, perhaps, is why married men live longer than single men and divorced women do better than divorced men. Despite the emotional, financial, and social hardships that divorce can entail, “increasingly,” Suzanne Brown Levine notes, “women are initiating divorce and regretting it less.”

13

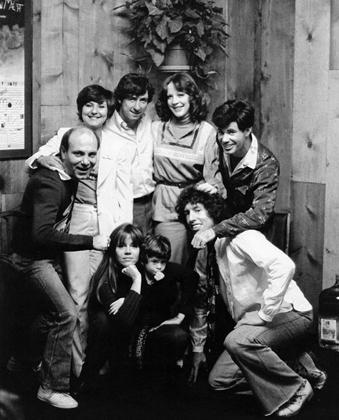

If a woman does decide later in life to take another chance at love, it is commonly with someone she knew previously. I met my current mate, Richard Perry, thirty-seven years ago, when he helped arrange for the musical group The Manhattan Transfer, which he was producing, to perform a fund-raising concert for my then-husband, Tom Hayden, who was campaigning for U.S. Senate. Here we all are in his recording studio in 1975. Richard is kneeling next to my son, Troy, and me. Tom is standing between Janis Siegel and Laurel Massey.

Me, Troy, Richard, and Tom (back row, center) with Tim Hauser, Janis Siegel, Laurel Massey, and Alan Paul of The Manhattan Transfer.

Long-Term Relationships

I have long been fascinated by how couples in long-term marriages have managed to adjust to the dramatic shifts that occur over the years, especially in the final third. It was one thing when our life span was twenty years shorter; I find it truly miraculous when a man who was “Mr. Right” during the years of building a family and raising children is still the right partner thirty, forty, or fifty years later. I am in awe, frankly.

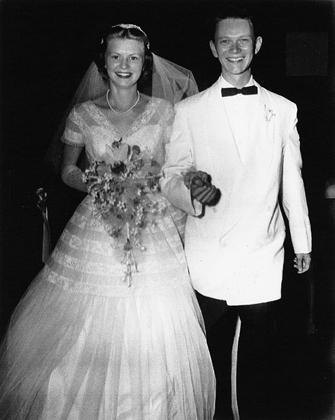

One such story is that of Bill and Kathy Stayton, who have been married for fifty-five years and have four children. Bill, seventy-six when I interviewed him, is an impish, courageous Baptist minister and sex therapist. I first met him a number of years ago, when I asked him to speak at a workshop on gender, sexuality, and religion at an annual conference of the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention.

Kathy Stayton, seventy-four, was an athlete in her younger days, and a school leader, and has kept her trim figure and natural beauty. Sitting next to Bill, quiet and attentive, she seemed the image of an old-fashioned, take-the-backseat homemaker. During our three hours together, however, I discovered a woman who, inspired by the peace activism of her family of origin, has, from girlhood, had her own firm voice.

I interviewed Kathy and Bill in their bright, one-story home in a newish development in Atlanta’s growing suburbs.

For eleven years, Bill had been a Baptist minister in Massachusetts. He found himself unprepared for the sexuality issues that came to him from his parishioners and from people in the community. He told me, “Sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, sexual dysfunction, multiple relationships, polyamory, and open marriage were life’s experiences presented to me—stories of things I didn’t even know existed and I was not prepared to help with. I’d go home and say, ‘Kathy, do you know people who do this?’ ” They both laughed at the memory. “I became really passionate about clergy being trained in human sexuality, no matter what,” Bill said. “So, I started taking courses in sexuality myself, became a doctor of theology in the field of psychology. I helped to found the Center for Sexuality and Religion. In 1997, the faculty and students voted to move the human sexuality program to Widener University, in Chester, Pennsylvania, where I served as professor and director. In 2006, I became the executive director of the Center for Sexuality and Religion, eventually at the University of Pennsylvania.”

In 2008, former U.S. surgeon general Dr. David Satcher invited Bill to come to Atlanta and merge the Center for Sexuality and Religion with the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine. Bill recently retired from being a professor at the medical school and assistant director of its Center of Excellence for Sexual Health.