Prime Time (11 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

I am always alert to people whose genetic inheritance makes them positive, able to turn lemons into lemonade. I try to hang with these types as often as possible, because their attitude rubs off. And, as you will learn in

Chapter 9

, most of us have a fair chance of becoming such people in our Third Act, even if we didn’t start out that way. On the other hand, I try to steer clear of people who walk around with a perpetual dark rain cloud over their heads, like Eeyore, the “woe is me” donkey in

Winnie-the-Pooh.

Often such people’s conversation focuses on themselves and their problems and how unfair the world is to them. They embody the Victim Motif. When I am with such types, I invariably wonder if they are aware of their negative vibe and if they’ve ever tried to get help moving out from under their cloud. It was only in the last decade of my Act II that I became aware of my own cloud and realized I had to try to do something about it. That is when I began taking medication, which helped me change gears and allowed me to open up to the benefits of talk therapy, after which I no longer needed the meds. We need some mileage under our belts before we are able to see that it is ourselves rather than others who are responsible for our willingness to accept rain clouds instead of going for the sun.

Me, fly-fishing with my golden retriever, Roxy, in 2001.

© VERONIQUE VIAL

I know that some of you reading this book don’t believe in therapy; maybe you view it as self-indulgent, the way my father did. But, according to author and therapist Terrence Real, “most psychological conditions can be significantly improved with the right care. Treatment for depression, for example, has been shown to be 90 percent effective. Yet only two in five depressed people ever get help.”

6

If temperament is inherited and relatively immutable, why are so many of us able to change how we feel and behave? My interest in the possibility of change stems from a sense I had, starting in my late twenties, that if I was to make my life all that it could be, I would have to change certain things about myself. My belief in the possibility of behavioral change is also what motivated me to found two nonprofits that aim at reducing risky sexual behavior among teenagers—the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention and the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health at Emory University’s School of Medicine.

In Georgia, around 1997, with some of the young men and women my nonprofit, the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention, worked with.

ON CHARACTER

Dr. George Vaillant addresses the issue of personal change in his book

Aging Well.

He says that while “temperament to a large extent is set in plaster,”

7

our character does change because it is influenced by environment and by our resilience, assuming we have inherited any. Resilience means that we can commandeer the resources, the good coping mechanisms, to deal with stressful situations. An example would be a forty-year-old woman who, in her young years, was sexually abused by her father. Instead of marrying a fourth abusive husband, she decides to run a shelter for abused women. I like Vaillant’s definition of resilience. He says it “reflects individuals who metaphorically resemble a twig with a fresh, green living core. When twisted out of shape, such a twig bends, but it does not break; instead, it springs back and continues growing.”

8

When I reviewed my Act I, I could see that I was blessed with resilience. My mother may have been MIA when it came to parenting, but my radar was constantly scanning the horizon in search of a warm, nurturing person from whom I could receive love and learning. Usually it came from the mothers of my best girlfriends. A child who lacks resilience may be in the presence of love but unable to take it in, to “metabolize” it, as George Vaillant puts it.

ON PERSONALITY

Okay. I have discussed temperament (permanent) and character (able to evolve). Where, then, does personality fit in? According to Dr. Vaillant, personality is the sum of temperament and character. This means that some of our personality is permanent (my needing solitude and my tendency to melancholy, which has been banished to a corner, yes, but hasn’t disappeared) and some is changeable (I am less judgmental and negative and more optimistic and loving).

Cognitive therapy has been shown to alter a person’s behavior. Working with a talented cognitive therapist, a person can begin to think differently about the past, for instance, and over time this new thinking activates different structures in the brain. This is referred to as “cognitive restructuring.” With practice and time, a person can begin to automatically think—and act—differently.

During their First Acts, most people are too young to think much about whether and how their character and personality ought to change. They haven’t had enough time to experience the ways in which they affect other people, to become aware of their behavioral patterns. Perhaps that can happen in Act II. As the playwright Nigel Howard once said, “The beautiful thing about learning a theory of your own personality is then you are free to disobey it.”

CHAPTER 4

Act II: A Time of Building and of In-Betweenness

Perhaps the practice of crossing the boundaries of work and rest, the habit of navigating transitions, of trying on new roles and personas, should be established earlier, allowing people to become familiar with, and adept at, reinventing themselves.

—SARA LAWRENCE-LIGHTFOOT

We now have an opportunity to exchange the wish to control life for a willingness to engage in living.

—ZEN PRIEST JOAN HALIFAX

Marching for welfare rights in Las Vegas in 1971.

I

N MY VIEW, ACT II SPANS AGES THIRTY TO FIFTY-NINE, AND DURING those three decades most of us go through a number of very significant transitions. These can be particularly dramatic for women.

Transitions

You may be looking back over this time in a life review, or, if you’re young, looking forward to it; in either case, these years typically can include the transition into parenting, then suddenly out of it, when you face the empty-nest syndrome (which can be a wonderful time for a couple, or hard to adjust to); the transition into more power in a job, then perhaps less, or losing a job altogether; and the hormonal shifts that mark the beginning of menopause, which may make us feel we are losing our minds. I felt this way! Because so many of us have postponed motherhood due to careers—births to women ages forty to forty-four increased 71 percent between 1990 an 1999—many of us go through the menopausal transition while we are still trying to cope with our teenagers’ own hormonal turmoil, and these difficult-to-navigate events may coincide with our being laid off from work because of age and our—in the company’s view—onerous seniority! To add to all this, we may find ourselves having to care for ailing parents and in-laws. All these things, together with potential changes in looks, weight, and self-image, can make us feel that our lives have peaked, that it will all be downhill from here on. That is certainly how I felt at this stage! But trust me, for many if not most of us, the best may be yet to come.

Try to think of this time as noted ob-gyn Dr. Christiane Northrup does when she calls it the “springtime of the second half of life.” I will write later about why this can be so!

In 1969, holding my daughter, Vanessa.

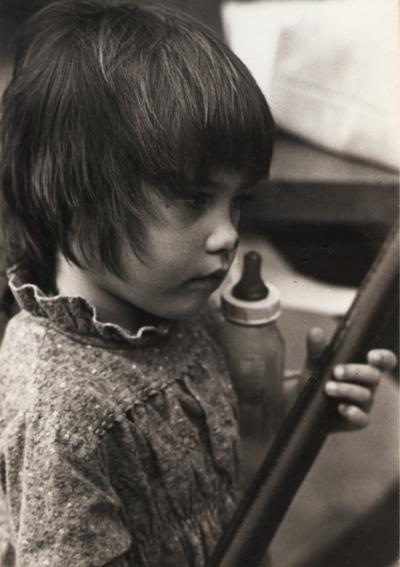

Vanessa in 1970.