Prime Time (7 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

My mother, around age 34.

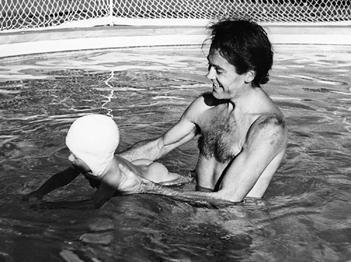

I studied family photographs, honing in on nuances of expression that might provide clues, hoping to recover proof of love in our family, love that was so rarely expressed. Yet I could see it on my father’s face as he played with me, at one year old, in our pool.

So he did love me when I was very little!

But how glum I was in childhood photos with my mother, as though deliberately sending a signal for all who cared to pick up on it that hers was not the team I chose to be on. Compassion opened my heart when I noted the desperation in my mother’s eyes in the photo of our family posed to look as if we were on a picnic, one year before her suicide. Forgiveness began to creep into my heart, forgiveness of her and also of myself.

I remembered how frightened I was of the noise of a motorcycle. During the Second World War, in the newsreels that would be shown in movie theaters before the main feature, Nazis were often shown riding motorcycles, so every time I heard one I would shout, “Get out of the way! Here comes Hitler!”

Dad playing with me in our pool.

Me around age two, making it clear to the camera that Mother’s lap was not where I wanted to be.

Mother, Dad, me, Peter, and Frances, my half-sister. Dad had just come home on leave from the navy during World War II.

I remembered the exhilaration I felt galloping bareback through the avocado groves in Pacific Palisades, California, unafraid, the Lone Ranger!

I tracked down Diana Dunn, my best friend from middle school, whom I had not seen in more than fifty years. She told me stories I’d forgotten, like the one about the time several of us found a dead snake in the road as we walked back from the hockey field. We scooped it up and put it inside the desk of a teacher we didn’t like. When she opened her desk drawer and saw the snake, she went into shock. All of us were called into the principal’s office and asked who was responsible for the snake. My friend told me that I was the only one who admitted to the prank. She recounted a similar experience when, during a sleepover at a friend’s house, we’d knocked over an antique lamp while playing hide-and-seek. Our friend’s mother was very upset and wanted to know who was responsible. I fessed up, and because of my telling the truth, the mother didn’t punish us.

I recalled the girl at summer camp who beat me up and rubbed my face in the dirt as she shouted, “Don’t think you’re special just because Henry Fonda is your father!” I refused to cry, but it lodged in my memory as a terrifying experience.

Newly discovered anecdotes like these gave me confidence, made me feel I had some good qualities after all, that I wasn’t just the lazy, foolish girl my father seemed to see me as. The faint outlines of a brave, resilient, honest little girl began to emerge, and I realized that I liked her, even if her parents hadn’t seemed to be too interested!

PARENTS, GRANDPARENTS, AND FAMILY

Perhaps the most important part of my research on Act I was that which I did on my parents and grandparents. I needed to know who they were behind the parental masks. What did they really care about, and why did they do the things they did? I focused on how my parents were treated by my grandparents, what state of mind my parents might have been in when they married each other and when I was born. I called and met with second and third cousins who knew my parents or grandparents; an aging aunt; and friends of the family who were still alive and reachable. I was like a sleuth, putting together the puzzle of a family, a self, a childhood, piece by piece. I began to see patterns and reasons behind things that had been boarded up in my house of memories.

I knew I was not the sort of person who could have done this life review and this family research much earlier. I needed the challenge of my Third Act to compel me to take the time and be brave enough to face it, to declare a memory open house, to seek the truth about myself and my family. Now I had an added incentive, too: I wanted to get my life right going forward.

Me, around age three.

Thus, I learned that there had likely been a long history of undiagnosed depression in the Fonda men, as well as what my cousins described as an almost pathological abhorrence for heavy women, especially those with thick legs.

Ahh.

My dad!

I learned that my father had always avoided any situation that would cause him to be emotional. He’d even refused to attend his mother’s funeral, choosing instead to stay in New York, where he was performing in a play. Work always came first for him, perhaps as a way to avoid real-life emotion. He didn’t even miss a performance of

Mister Roberts

to be with Peter and me the night our mother killed herself. (I learned that she had not died of a heart attack only when, a year later, I read in a gossip column that it had been suicide.)

My grandfather William Brace, Aunt Harriet, Dad, Aunt Jayne, and Herberta, my grandmother.

Members of the Fonda family, including Sue Fonda, David’s wife; Aunt Harriet; Becky Fonda, Peter’s wife; Peter Fonda; Tina Fonda; David Fonda; me; Cyndi Fonda Dabney; and children, gathered on the porch of Dad’s birth home at the Stuhr Museum in Nebraska.

Family picnic in Omaha, July 1907. Front row, left to right: My father in the lap of my grandmother Herberta, Ethelyn Hinners Fonda holding my aunt Jayne, my grandfather William Brace holding my aunt Harriet. Back row: my great-grandmother “Grammie” Hattie, unknown (could be Hattie’s sister), and my great-grandfather, Ten Eyck Hilton Fonda, Sr.

Dad’s father and mother in front of their home in Omaha.

ACT II

In my second act, the rap on me was that “there was no there there,” that I was only whatever my current husband wanted me to be. In fact, when I asked my daughter, who has made documentary films, to help me with the autobiographical video I was shooting for my sixtieth-birthday party, she said, “Why don’t you just get a chameleon and let it crawl across the screen?” I knew that one important thing I needed to find out through my life review was whether this opinion of me was true. I secretly thought that maybe it was.