Prime Time (10 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

Like many girls, I first began to experience anxiety and depression during adolescence. That is also when my twenty-year-long battle with anorexia and bulimia began. As I know all too personally, this doesn’t end with adolescence but is a pattern of disembodiment that, unless consciously broken, can make intimate relationships nigh impossible; we are not bringing our whole selves to the table—literally and figuratively! If we manage to break the pattern of anxiety, disembodiment, and addiction, then, in our Third Acts, we will be able, as the psychologist Carol Gilligan says, to find our way back to the spirited ten- and eleven-year-old girls we once were,

before

our voices went underground—only better, wiser.

If you are a woman, think about your own adolescence. Did you feel you had to conform to culturally imposed stereotypes of femininity, or did you have an authentic relationship to your sexuality and to your gender? Did you

own

it? Were you able to embody your sexuality because someone made sure you understood that sexuality isn’t just about the act of sex, it’s also about sensuality and feelings? Were you made to feel you had to look and behave a certain way if you were to earn love? Were you supposed to be seen and not heard? Did you have someone who made you understand that your feelings and ideas were as valuable as a boy’s? That you could be strong and brave as well as caring and giving? What kind of role model was your mother? Did she express her own opinions? Take some time for herself? Did your father rule the roost and your mother always acquiesce? How did your father respond to your adolescence? Did you feel you weren’t pretty enough or good enough or thin enough?

This is all so subjective, isn’t it? Some of the most beautiful women I know think they are unattractive because of early messages, and some not traditionally attractive women exude confidence and beauty because that’s how they were made to feel growing up. Did one or both of your parents act as a buffer to the misogynist media? Did they talk to you about how ridiculous it is that so often advertisements use ultrathin, stereotypically sexy girls and women or macho, super-buff men to sell things? Ads can make women and men feel anxious about how they are (real life) in order to persuade them to buy things that, the implication is, will make them more acceptable—like the models.

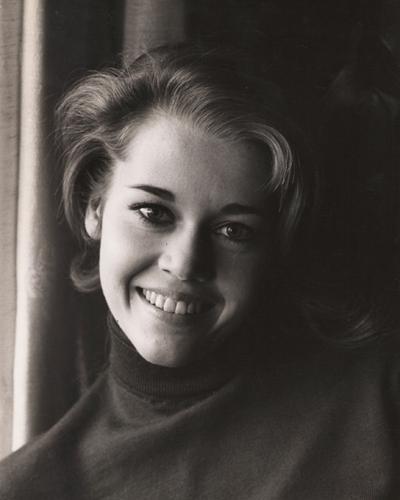

Me, age 22.

BOYS

From my friend Carol Gilligan, a psychologist, a writer, and the mother of three sons, I learned that one of the big differences between girls and boys is that girls’

voices

go underground at adolescence, whereas boys’

hearts

go underground when they are around five or six years old, the age when they begin formal schooling, leave home, and are exposed to the broader culture. If you are a man, did your parents or your teachers make you feel like a sissy if you cried, or a momma’s boy if you walked away from a fight? Were you taught that a “real man” would never let anyone get away with shaming him and that shaming had to be met with violence? Did your template for manhood mean having to choose between a nonthinking, nonfeeling macho man and a New Age wimp? Did you have an adult who helped you understand your uniqueness, that you weren’t better than girls but wonderfully different? Did they instill in you an admiration for attributes like being present, brave, trustworthy, focused, goal-oriented, or a good team player? These are positive masculine qualities (good for women, too!). As a boy, did you feel it was okay to be wrong? Did you find it hard to ask for support? Did you believe that asking for help showed weakness and vulnerability? Did you feel pressure to prove your manhood and, if so, did you ever wonder why it needed to be proven as opposed to its being assumed as a part of your innate, authentic self? Were you helped to believe that a real man or woman is one who refuses to be casual about sex, who respects his or her own body enough to not be nonchalant about giving it away?

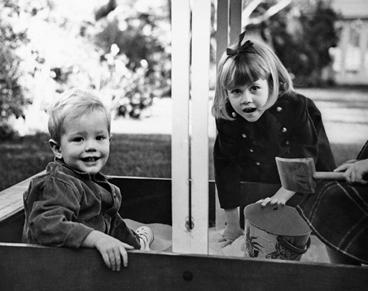

At around age four with Peter, my brother—two years younger—playing in the sandbox.

It is at this early age that so many boys are encouraged to bifurcate head and heart so that they will be “real men.” They become emotionally illiterate to the point where they often don’t even know what they are feeling and they lose their capacity for empathy, the ability to feel what others are feeling. And it happens so early that for men it is just the way things are. They can’t remember a time when they felt differently. The psychologist Terrence Real, in his wonderful book about men and depression,

I Don’t Want to Talk About It,

writes, “Recent research indicates that in this society most males have difficulty not just in expressing but even in identifying their feelings. The psychiatric term for this impairment is alexithymia and psychologist Bon Levant estimates that close to eighty percent of men in our society have a mild to severe form of it.”

4

For boys, this can manifest in signs of depression, learning disorders, speech impediments, and out-of-touch and out-of-control behavior.

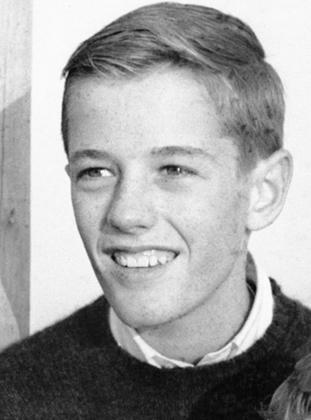

Brother Peter as a young teenager.

Obviously, not all boys experience the early trauma of manhood. It seems that a warm, loving, structured home and school environment can act as a vaccine, helping boys stay whole. Were you lucky enough to be surrounded by adults who showed you explicitly or by example that being a man means being a whole human being—strong

and

emotional, brave

and

compassionate?

In today’s Western culture, most men are still very vulnerable to shaming, to being seen as not manly enough, and this affects every part of men’s lives—and women’s, as well.

Consider the economy. In her book

Backlash,

Susan Faludi writes about an opinion poll that asked men and women around the world how they defined “masculinity.” Overwhelmingly, the response was “Masculinity is the ability to bring home the bacon, to support their family.” So, if this is the main criterion for masculinity everywhere in the world, what happens when the economy goes south, jobs become scarce, and it is women who are bringing home the bacon (albeit for lower wages and benefits)? Violence against women goes up because men feel ashamed.

Or consider issues of war and peace. In his book

War and Gender,

Joshua Goldstein, a professor of international relations at American University, wrote, “As war is gendered masculine, so peace is gendered feminine. Thus the manhood of men who oppose war becomes vulnerable to shaming.”

The Pentagon Papers showed us that in the 1960s and ’70s, the advisers of four different administrations—Republican and Democrat—told their presidents that the Vietnam War could not be won short of annihilating the entire country, and yet our leaders kept sending more young men to fight. I wondered about this, and then I read Doris Kearns Goodwin’s biography of President Lyndon Johnson. He told her that he feared being called “an unmanly man” if he pulled out of Vietnam. This seems to be an ongoing pattern in the United States—a fear on the part of our male leaders of premature evacuation!

In the 2004 presidential campaign, when Democratic candidate John Kerry spoke in favor of upholding international law and supporting the United Nations, he was called “effete” by Vice President Dick Cheney. There’s that masculinity thing again, as though advocating for peace and diplomacy is effeminate.

I cite these examples because gender is such a core issue affecting every one of us—not because all boys and men are potentially violent and hawkish, but because the root of what surfaces in

some

of our boys and men as violence and hawkishness exists in too many of them as lack of empathy, emotional illiteracy, inability to be authentic, and vulnerability to shame. When adults help boys and girls shape their identities without resorting to gender stereotypes, they prepare them to have an optimal chance at future relatedness and intimacy in the stages of life to come.

A noteworthy shift has taken place over the past thirty years. Psychologists have come to believe that the highest form of human development lies not at the extremes of the gender-role spectrum—men as autonomous and dominant, women as dependent and malleable—but in the middle, where true, authentic relationships take place. From Jung forward, most psychologists have recognized that only when partners are able to let go of rigid, hierarchical sex roles can there be intimacy and authenticity.

In a later chapter, I explain the good news that as we enter our Third Acts, a great many of us, women and men, tend to move away from damaging sexual stereotypes and, as a result, find deeper intimacy and more gender parity in our relationships.

As I have learned from Carol Gilligan, gendered adolescent behaviors are not simply a matter of biology—“boys will be boys” and “girls are just experiencing hormonal surges.” Psychological and cultural factors also play a role. In addition, the success of programs that encourage girls’ interest and performance in math, science, and sports and the proven benefits of interventions that help young men get in touch with their emotional lives argue against a simple biological determinism.

That’s not to say that boys and girls are the same. Today’s brain science has revealed beyond a doubt that there are many innate and universal differences in how we think, how we see, and how we react to various circumstances. We need to respect those differences, while also not letting them become exaggerated, overly self-conscious expressions of what “masculine” and “feminine” mean.

For the health of our boys, we need to define the positive qualities of being male. It is hard for a boy to learn to be both tough and tender—and then to learn to integrate the two into appropriate behavior so they can become holistic men who can move toward intimacy and communion and not feel that empathy and emotions mean weakness.

How Much Can We Change?

Like many people, I went through my First Act pretty much on my own in terms of figuring things out. My dad was a naval officer in the Pacific during most of World War II, but when he was home, I learned important things from him, mostly by osmosis (and from the roles he chose to portray in theater and movies)—about fairness, sticking up for underdogs, and the wrongness of racism and anti-Semitism. No one taught me about sex, however—how to know if a relationship was real, that it was okay to say no and to honor my body. Maybe this is why understanding these things (and writing about them) and trying to teach them to young people became important to me toward the end of my Act II. Part of this has to do with understanding in what ways people do and don’t change. If in your First Act you did not receive much guidance of the sort I have just written about, how can you get over it? What might be some ways? Frankly, I wouldn’t be writing this book if I didn’t think change was a real possibility.

ON TEMPERAMENT

Psychologists generally agree that our temperaments are mostly hereditary and that while they can be modified to some slight degree, we are pretty much stuck with them. Temperament is what determines the level of our tested IQ and “the genetic component of our social intelligence”

5

—whether we are introverted or extroverted, sullen or positive, rigid or resilient. I saw clearly, while reviewing my first two acts, that my genetic temperament makes me someone who was dusted with a sprinkling of depression; this became more acute during my adolescence and early twenties. The trait came mostly from my father’s genetic line; I consider it blind luck that I didn’t inherit my mother’s bipolar genes. Time, therapy, and a decade of psychopharmacological assistance during the end of Act II allowed me to mostly banish my depression to a corner; it lurks there still, trying occasionally to send out negative, “who do you think you are” scenarios that I refuse to read. I am also someone who likes solitude for long stretches (my father’s genes). But when I’ve had enough aloneness, I become very sociable, outgoing, and even garrulous (my mother’s genes). Maybe this is why the animal I have always identified with is the bear, which hibernates during the long winters and then loves to play and socialize.