Prime Time (12 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

Vanessa at ten years old.

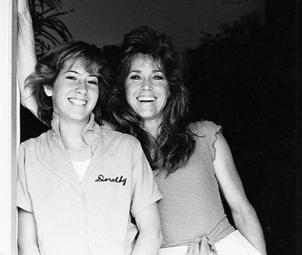

Around 1985, with Vanessa.

© 2001 SUZANNE TENNER

In

My Life So Far,

I called Act II “Seeking” because, as I looked back, I could see that, for me, the defining feature of this act was the search I undertook to find meaning in my life. I’d ended my First Act playing Barbarella! With the start of my Second Act—and, with it, the birth of my first child—I left my marriage of eight years, profoundly changed the way I lived, and began asking,

What am I here for? What are other people’s lives like? Can I be useful?

For most people, Act II might be called “Building,” because this is when we are building families, careers, our place in society, and our egos. As a result, during this act we are so vulnerable to the many challenges to our egos: Am I being recognized as much as she is? Am I getting paid what I deserve? Why has his business plan worked and mine hasn’t? Why does no one love me? That sort of thing!

Dr. George Vaillant writes, as mentioned previously, that in early midlife, childhood is still significantly important, whereas “unhappy childhoods become less important with time.”

1

Those of us with challenging early lives may have a harder time of it as we enter our Second Acts. We’re supposed to be becoming

someone,

but we can’t quite find our footing and may—involuntarily—still resort to immature coping mechanisms such as acting out, projection (imposing one’s own thoughts and feelings onto another), or passive-aggressive behavior. A number of long-term studies over the last forty years have shown that maladaptive coping mechanisms such as these can mature into altruism and sublimation as we age, but while we’re in the midst of it, life can be so hard.

It seems to me that those who do the best in their Act III are those who began to manage their egos while they were younger; they became aware of their character traits, how and why others responded to them the way they did, and, if the responses were problematic, asked themselves if perhaps their own behavior, their own thinking, might have been the problem. Often people with immature coping traits blame everyone else for what goes wrong. They have what I call a “the world is full of assholes” attitude. This is especially true of people with addictions. If the same problems keep arising, one should consider getting help, either with individual therapy or group therapy, or with a twelve-step program.

In our parents’ time, it was common to graduate from college and go right into a career or, for many women, into the unpaid but challenging jobs of marriage and parenthood. These days, many more—perhaps most—women are working, and for both women and men, changing careers not once but numerous times during the Second Act is not unusual. Nor is starting a career, marrying, divorcing, and reentering the workplace. Maybe Act II should be called “Churn.”

Finances

Act II is the optimum time to take a careful and honest look at your financial situation. Your future security may depend on your starting a savings plan now. Midlife is also the ideal time to develop a healthy lifestyle, if you haven’t done so already—it will help maximize Third Act potentials. I will discuss this in later chapters.

The Challenge of In-Betweenness

During the middle to latter part of the Second Act, especially between the mid-forties and the mid-fifties, many women feel they’re losing control of life and have nothing to hold on to. I certainly felt this way. I call it the challenge of in-betweenness, and it’s scary. As Marilyn Ferguson has written, “It’s not so much that we’re afraid of change or so in love with the old ways, but it’s that place in between that we fear.… It’s like being in between trapezes. It’s Linus when his blanket is in the dryer. There’s nothing to hold on to.” How we handle our time between trapezes can determine much about how well we swing into the rest of our lives.

I THOUGHT I WAS DISAPPEARING

In my late forties, joy seemed to be leaching out of my life. When I look at photos of myself during that period, I see a blankness on my face. It’s as if nobody was home. I watch my movies from that time

—Old Gringo

and

Stanley & Iris,

in particular—and I can tell. It felt as if I was uninhabited, going through the motions—sometimes fairly well, but with no hookup to the heart. Those were the last movies I made for a long time. I quit the movie business after them. Fifteen years later I went back, but at the time I thought I was finished with it forever. I felt so empty, so low, that it was just too painful to try to be creative. You see, the only instrument an actor has to bring a character to life is her or his own body and spirit, and if those are shut down, there’s nowhere else to turn—no violin, no canvas, no pen and paper. That’s not to say that many actors don’t continue their work despite personal meltdowns. Work may provide their only escape, or maybe it’s their only source of income. I was fortunate in that the Jane Fonda Workout business was bringing in enough money for me to be able to stop acting.

I looked ahead and saw no future beckoning, yet I had to plow onward. I had a family, organizational responsibilities, and myriad other duties. Besides, it’s not as though I understood what was going on. What was I going to say to those who depended on me? “I don’t know why, but I feel like I’m disappearing, like I’m getting all blurred around the edges”? They would have thought I was mad, and in a way I was.

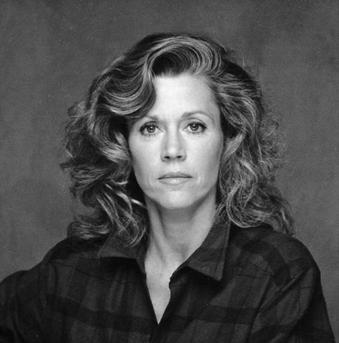

Me in 1988, as my marriage to Tom was falling apart—and so was I.

MARY ELLEN MARK

I was sure that if the approach of menopause was to blame I’d be experiencing hot flashes and night sweats; since that hadn’t happened, I lay the blame for my sadness, confusion, and irritability on my deteriorating second marriage of seventeen years, to Tom Hayden.

In the 1970s—Tom Hayden, our son, Troy, and me, with my daughter, Vanessa, peeking from behind.

Despite the fact that I was researching and writing

Women Coming of Age,

it didn’t occur to me that what was happening, at least in part, were the effects of perimenopause, that varied stretch of time leading up to menopause when women begin to experience the erratic cycling of hormones, and the estrogen and oxytocin levels in our brains begin to drop. These substances support our mood-elevating serotonin-releasing cells, the ones that make us feel good. According to the neuropsychiatrist Dr. Louann Brizendine, at the University of California, San Francisco, perimenopausal women are fourteen times more at risk of depression than younger and older women. Of course, many women sail through this hormonal transition with very little difficulty. But according to the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States, life can take a downward turn for more than two-thirds of women between the ages of thirty-five and forty-nine. After that, once the hormones have stabilized with the completion of menopause (which happens, on average, at age fifty-one and a half years), life can take a surprisingly upward turn for a great many women.

One of the last Christmases Tom and I had together. Troy is behind and Vanessa is on the right.

Hormonal Shifts

Another factor comes into play as we approach and enter menopause, one that can have a complex effect on our interpersonal relations: Our estrogen and oxytocin levels begin to drop below those of the more masculine, goal-oriented testosterone. Those feel-good hormones were what encouraged us to take care of others, smooth things over, and avoid conflict. Now we may find ourselves not caring so much about keeping the peace, and we may express our previously repressed anger more openly. Old Let-Me-Take-Care-of-It-for-You-Honey morphs into I’m-Going-to-Class-See-You-Later-and-the-Cleaning’s-Ready-to-Pick-Up. Contrary to what we may think, 65 percent of divorces after age fifty are initiated not by men wanting to leave their wives for younger women but by the wives themselves. They may start to ask themselves, “Have I lived my own life or the life others have wanted me to live, making decisions others wanted me to make rather than my own?”

Had I known what was behind my depression and anxiety as I approached fifty, I might have sought help from a doctor who specialized in hormone therapies. This, I have since learned, is the optimal time for healthy women who are experiencing perimenopausal symptoms to consult their doctors about hormone therapy in low doses. (I will discuss hormone therapy at greater length in

Chapter 14

.)

Breakdown

Even with pharmacological help, my marriage would have ended sooner or later. I was fifty-one when it happened and, always the late bloomer, still going through perimenopause. All the sadness and despair I had been experiencing over the previous several years crashed in on me. My lifelong, ever-ready carapace fell apart, and I had a nervous breakdown. I couldn’t eat or speak above a whisper or move quickly. I was in free fall. Everything I had relied on for self-definition—marriage, career—was stripped away, and I hadn’t a clue about who I was or what I was supposed to do with my life.