Prime Time (8 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

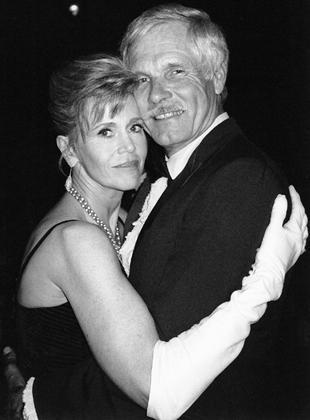

With Ted at my sixtieth-birthday party.

ERIC WITTMAYER PHOTOGRAPHY

But as I delved deeper, I could see evidence of a new, stronger me starting to emerge. I felt as though I was

owning

myself for the first time.

There is a there there!

PHYSICAL ABUSE

The most profound event for me during the writing of my memoirs was when I was able to obtain my mother’s medical records from the mental institution where she killed herself. In them, the doctors noted that my grandfather had had the symptoms of a paranoid schizophrenic. He’d boarded up windows and kept the front door bolted because he feared that some man would come and steal his beautiful, much younger wife. The records included a fifteen-page autobiography written by my mother, I assume upon admittance, at the request of the doctors.

In her own words, she revealed that she had been sexually molested at age eight by the piano tuner, the only man my grandfather would unbolt the front door for! All my adult life I had wondered about my mother’s childhood. The older I got and the more I understood about the long-term effects of early trauma, the more I intuited that something bad must have happened to her. Maybe that’s why I had been drawn to studying childhood sexual abuse over the previous five years. My research enabled me to understand what my mother meant when, in recounting her middle and high school years, she wrote, “Boys, boys, boys.” I was able to connect the dots upon reading that she had had six abortions and plastic surgery on her nose and breasts before I was born, in 1937, and that her psychiatric tests at the end were, according to the doctors’ reports, “replete with perceptual distortions, many of them emphasizing bodily defects and deformities.”

By the time I read my mother’s reports I already knew that sexual abuse, be it a one-time trauma or a long-term violation, is not only a physical trauma; its memories carry a powerful emotional and psychic charge and can lead to emotional and psychosomatic illnesses and

difficulties with intimacy.

The ability to connect deeply with others is broken, and it becomes difficult to experience trust, feel competent, have a sense of self. Thus, another piece of the family’s intimacy puzzle fell into place.

I also knew that sexual abuse robs a young person of her sense of autonomy. The boundaries of her personhood become porous, and she no longer feels the right to claim her psychic or bodily integrity. For this reason, it is not unusual for survivors to become promiscuous starting in adolescence. The message that abuse delivers to the fragile young one is: “All you have to offer is your sexuality, and you have no right to keep it off-limits.”

Boys, boys, boys.

GUILT

Then there’s the issue of guilt. It seems counterintuitive that a child would feel guilty about being abused by an adult whom they are incapable of fending off. But children, I learned, are developmentally unable to blame adults. They must believe that adults, on whom they depend for life and nurturing, are trustworthy. Instead, guilt is internalized and carried in the body, often for a lifetime—a dark, free-floating anxiety and depression that can cross generations. This can lead to hatred of one’s body, excessive plastic surgery, and self-mutilation.

I had learned, years before I’d read my mother’s history of abuse, that these feelings of guilt and shame, the sense of never being good enough, and hatred of one’s body can cast a long shadow. These emotions can span generations, carried on what feels like a cellular level to daughters and even granddaughters.

So that’s partly where they came from, my own body issues, my feeling of not being good enough!

Reading my mother’s typed history, with her little penciled notes in the margins, filled me with sadness and with compassion for my mother, as well as gratitude that, fifty years later, her history would allow me to forgive her—and myself. Again the realization swept over me:

Her remoteness, her suicide had nothing to do with me. I don’t have to feel guilty.

This was an important lesson, this understanding that other people have lives and problems you know nothing about—their behavior is not all about you!

Talking to her few remaining friends and family members, I discovered that my mother, whom I remembered as a nervous, fragile, nonsexual victim, was viewed by her contemporaries as a “rock” on which they could lean in times of need, an icon, an extremely sophisticated, sexy, ebullient woman who attracted men “like moths to a flame.” It took me a while before I managed to replace the pathological version of a mother whose genes I share but had rejected for six decades with this new, powerful vision of her. Maybe she wasn’t able to be the mother my brother and I needed, but she had so many other fascinating, capable, lovable parts to her. I was finally able to see more of the totality of her. This was a mother I wanted to own, and owning her meant that the love-denying defenses I had erected against her came tumbling down. I felt a new lightness of being and knew I was finally coming into my own.

I have written about much of this in my memoirs, but I repeat the stories here because they are so important to me. Perhaps my telling them will trigger your own remembrances of formative experiences. Especially important for me was the discovery of my mother’s childhood sexual abuse. One out of three girls is an abuse survivor, and there is a real possibility that such a trauma has cast a shadow over your own family. You won’t know unless you ask.

In doing my life review, I read books by the famed psychologist Alice Miller;

The Drama of a Gifted Child

was especially useful. It is about people who survived emotionally and physically abusive childhoods with narcissistic parents because they developed adequate defense systems. Also useful was

I Don’t Want to Talk About It,

by the therapist Terrence Real, which addresses men’s depression and their difficulty in expressing emotion. My goal was to better understand my father. As it turned out, however, these books also helped me understand my three husbands! Terrence Real writes about the many ways men unconsciously disguise depression with addictions, and about how hard it is for them to allow people to see their underlying sadness. It isn’t manly! This permitted me to view the significant men in my life with forgiveness and compassion. What a wonderful gift to bring into my Third Act!

FORGIVENESS AND GRATITUDE

Forgiveness is at the center of it all, and gratitude. I was able to see how many people had given me so much, had believed in me even when I hadn’t. On a deep, noncerebral level, I could separate who I was from how my parents had behaved toward me.

MY LATE FORTIES AND FIFTIES

When I looked back at Act II, especially my late forties and fifties, I saw that I got stressed out so easily then. I remember feeling like Sisyphus trying to roll a boulder up a mountain. I thought that this was just life. I’d wake up in the morning and my first six thoughts would be negative. I realized that my negativity had been increasing as I aged, and I grew concerned.

Today I do not suffer from the “poor me”s; there is no longer a blanket of negativity weighing me down. I no longer react to today’s dramas with my own drama, partly because I’ve replaced stress with detachment. By that I don’t mean indifference but, rather, an ability to step back and observe events with greater objectivity, fairness, and perception instead of so much subjectivity. This detachment can be one result of doing a life review. Understanding leads to the realization that

it’s not just about you!

I have been able to carry this newly discovered perspective and wholeness with me into my Third Act—proof that it’s never too late!

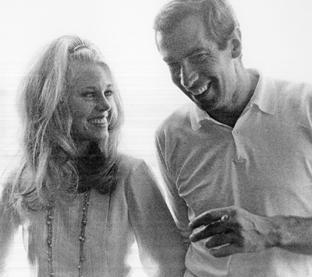

With Vadim on our wedding day.

Tom Hayden with Vanessa and Troy.

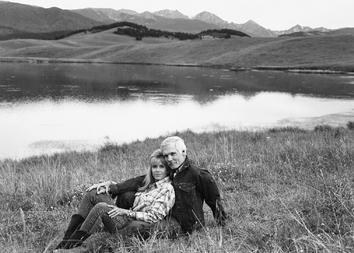

With Ted at one of his ranches in Montana, in 1977.

© ANNIE LEIBOVITZ/CONTACT PRESS IMAGES

Decommissioning Our Demons

What the experience of doing a life review has taught me is that while we cannot undo what has been, we can change the way we understand and feel about it, and this changes everything. It helps us decommission our demons, frees us from the past, and gives us a boost as we go forward, in new ways, into the rest of our lives.

Self-Confrontation and Transformation

While researching this book, I was surprised to find that a number of psychiatrists advocate the life review process, not for the purpose of wallowing in past problems or pathologies or enshrining our early years in either joy or pain, but as a means of self-confrontation and transformation. We look back, we take responsibility for ourselves, and we move on.

The late Dr. Robert Butler, who was the founding president of the International Longevity Center in New York City, said, “There is a moral dimension to the life review because one looks evaluatively at one’s self, one’s behavior, one’s guilt.” He believed that a life review can lead to atonement, redemption, reconciliation, and affirmation and can help one find a new meaning in life. He noted that “if unresolved conflicts and fears are successfully reintegrated, they can give new significance and meaning to an individual’s life.” I know this can be the case; I have experienced it and the freedom it brings. So, step one in making a whole of your life is spending time on a life review.

As mentioned earlier, Viktor Frankl’s idea that you have the freedom to choose how you respond to a given situation influenced me greatly. Approaching the matter from a different vantage point, quantum theorists have reached a similar conclusion, maintaining that “we determine reality by the manner in which we approach it. If we observe from a different perspective, we ‘discover’ a different reality.”

1