Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (15 page)

Read Qatar: Small State, Big Politics Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

In solidifying the international regimes that ensure their positions of dominance, hegemonic powers seek to persuade others to buy into their vision of the world order and to defer to their international leadership in various arenas of concern, especially in the areas of security and international trade and finance.

78

At the same time, hegemonic leadership must constantly recreate the conditions of its own existence in order to avoid collapse, complementing the relationship between the hegemon and its subordinates with healthy doses of cooperation and protection.

79

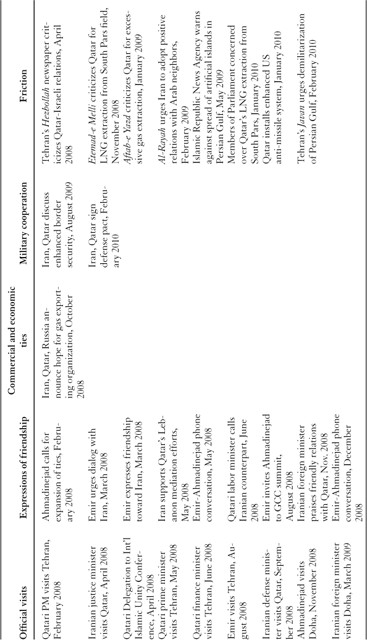

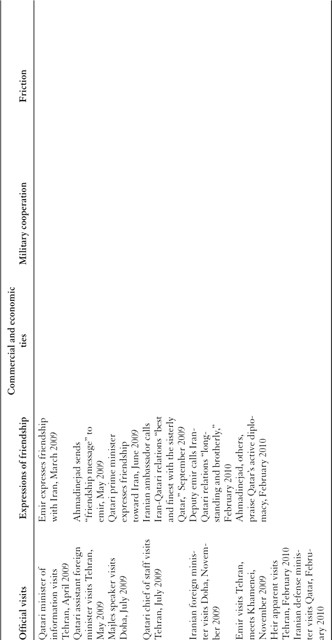

In Qatar’s case, the country’s approach to the United States also reflects its leaders’ cultural, political, and commercial preferences. The emir and his inner circle have made a deliberate decision to pursue a US-centric path of economic development and cultural change, one that is given official sanction through various forms of royal patronage, and is guaranteed by the US security umbrella. This is reflected in the plethora of institutional arrangements that underwrite the three primary pillars of Qatari-US relations. At the same time, the Qatari state strongly resists the development of in-depth institutional ties with Iran, mindful that such arrangements might, intentionally or unintentionally, resonate with the sensibilities of the country’s otherwise compliant Shi‘a population. Nevertheless, Qatari leaders maintain quite warm and friendly personal relations with their Iranian counterparts, with the primary motivator on the part of the Qataris appearing to be fear. This fear appears to be rooted in two possible scenarios: first, that Tehran’s frictions with Washington do not translate into frictions with Doha despite the deep and multifaceted nature of Qatari-US relations; second, that in the event of Iran somehow finding itself attacked or under increased pressure, the Qataris of Iranian background would not fault Qatar for being complicit in an anti-Iranian front. Ultimately, Qatar’s warm relations with Iran appear to be a direct byproduct of—or, more accurately, a reactive impulse to—its wide-ranging and institutionally ingrained relations with the United States.

Given the preponderant US military presence in the Persian Gulf, irrespective of Qatar’s security concerns, the sheikhdom to a large extent benefits from “free riding,” while maintaining a significant amount of structurally rooted cooperation that characterizes the relations between the two countries. We know that “the longer one’s time horizon, the greater the rewards from mutual cooperation are in comparison to fleeting benefits from free riding.”

80

As the narrative here indicates, Qatari-US cooperation is systematic, multidimensional, and built on long-term assumptions. As such, despite occasional differences over priority and policy, it is likely to remain resilient and robust for the foreseeable future.

An effective survival strategy, Qatar’s carefully balanced hedging has served it well. Apart from Oman, Qatar is the only other Persian Gulf state with whom Iran has not had any contentious issues since 1979.

81

The sheikhdom has cultivated an image of evenhandedness and balance that few of the other states in the Middle East can claim to have. As such it has emerged as a trusted “honest broker” that is well positioned to mediate conflicts. Its alliance and friendship is not taken for granted and is actively courted by both Iran and the United States. And, correspondingly, despite its strategic position at the mouth of the Hormuz Strait, it enjoys perhaps the largest immunity from any intentional or unintentional spillover of a military conflict involving Iran and other international actors, most notably the United States and Israel.

Military Security and Protection

Military and security arrangements underwrite the larger context within which US-Qatari relations unfold. Unlike many of its regional neighbors, particularly the UAE and Kuwait, Qatar does not have a credible military force of its own. It has an estimated total of 12,000 individuals in uniform, plus an additional 8,000 employed in the public security forces. Of these, an undisclosed but disproportionately large number are non-nationals from Yemeni and Pakistani backgrounds. Part of the problem is demographic: there simply are not enough Qataris of a militarily significant age to address the country’s growing military needs. At the same time, military service is not a career path to which most young Qataris aspire, drawn instead to the private sector and the prospects of secure, prestigious white collar positions fattened by the state’s labor Qatarization policies.

Equally important appear to be deliberate decisions, made at the highest levels of the state, to relegate the country’s defense to the much more powerful, and in the Persian Gulf omnipotent, United States. According to one of the cables from the US embassy in Doha, “the QAF (Qatar Air Force) could put up little defense against Qatar’s primary perceived threats—Saudi Arabia and Iran—and the U.S. military’s presence here is larger and far more capable than Qatar’s forces.”

82

In the Americans’ assessment, Qatar lacks a comprehensive national military strategy, and the Qataris have been cool to the US military’s proposal to draw up one for them.

83

Similarly, unlike its regional neighbors, Qatar’s requests for the purchase of advanced US weaponry have been modest over time, and at times the Qataris have backed out of weapons deals with the United States.

84

Precisely why the Qatari leadership has chosen to pursue an apparently minimalist military policy is hard to answer. Part of the calculation must surely involve the country’s small size as compared to Iran and Saudi Arabia—why start an arms competition that cannot possibly be won? Another reason appears to lie in the emphasis on domestic infrastructural development and on international investments. Knowing there is the US protection to rely on, the Qatari leadership appears to have made a strategic decision to focus its financial resources on other endeavors. And, lest the Americans take the Qataris for granted, there is always hedging to remind them otherwise. The US embassy appears to have read the Qatari strategy correctly:

We believe Qatar wishes to make incremental improvements in all components of its military, with the caveat that such investments will remain subordinate to the primary national goal of economic and human development…. Qatar’s desire to be the “friend of everyone and enemy of no one” means that politics will remain a crucial factor in any defense purchase decisions.

85

Qatar is home to two large US bases, the Al Udeid air base, which is estimated to house as many as 10,000 US military personnel and more that 120 aircraft, and the As Sayliha, which houses the Army component of the US Central Command.

86

Al Udeid, which has the longest runway in the Persian Gulf, was built by the Qataris in 2000 at an estimated cost of more than $1 billion. The two facilities constitute the largest pre-positioning bases outside of the United States.

87

From 2002 to 2011, the United States is estimated to have spent more than $459 million in the expansion and upgrading of the Al Udeid Air base alone.

88

For 2012, the US administration requested another $37 million from Congress to continue the base’s construction projects. In 2012 the Pentagon was reported to be building a missile-defense radar station at a secret location in Qatar at a cost of $12.2 million.

89

As part of its overall foreign and security policies, the Qatari state is committed to “a broad strategic partnership with the United States.”

90

American officials are therefore repeatedly assured that for Qatar “maintaining strategic relations with the United States is the ‘number one priority’ and that Qatar ‘will never change’ that alignment.”

91

What appears to be neglect on the part of state elites of a key component of national defense is, in fact, part of a deliberately calculated decision to rely on an outside, far more powerful patron. But reliance on the US for defense and security ought not to be conflated with a policy of bandwagoning and aligning foreign policies and priorities in a way to match those of the United States. Qatar needs and likes the American military protection; it would be otherwise defenseless on its own. But it also likes its foreign policy independence, as manifested in its hedging, as a way of maintaining open lines of communication with as many disparate international actors as possible, friend and foe alike.

Branding and Hyperactive Diplomacy

Qatar’s diplomatic hyperactivism, made possible by an efficiently run and cohesive state, occurs concurrently with—and is reinforced by—an intense campaign of branding the country. In the ultra-competitive era of globalization and in the race to attract ever-greater levels of direct foreign investment, states often embark on aggressive campaigns of branding in order to acquire positive reputations both generally and in specific areas. The explosion of the international media and the accessibility of global communication networks have made a country’s image and reputation central to its economic and diplomatic success. According to one observer of the phenomenon, “branding has emerged as a state asset to rival geopolitics and traditional considerations of power.”

92

In fact, maintains another, “the unbranded state has a difficult time attracting economic and political attention.”

93

Since the mid-1990s, Qatar has emerged as a “brand state” par excellence, with concerted efforts underway in multiple areas of politics, economics, sports, and culture.

94

Slick advertisements in glossy magazines and on TV screens across the world often showcase Qatar Airways (billed as “the world’s five-star airline”); Qatar Foundation, which is said to “help the world think”;

95

the Museum of Islamic Art, with its world-class art collection; and the country’s business-friendly environment. Securing a place for itself as a hub for major world sporting events, the country hosted the 2006 Asian Games, unsuccessfully bid for the 2016 Summer Olympic Games, hosted football’s Asian Cup in 2011, and shocked the sporting world by winning the bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Despite the scarcity of Qatari-born athletes, Doha frequently hosts international tournaments in handball, football, track and field, and gymnastics. In November 2012, meanwhile, Sheikha Moza announced the creation of a global program in collaboration with the United Nations designed to educate 61 million children worldwide who have no access to formal schooling.

96

In these respects, Qatar’s branding efforts are not greatly different from those undertaken by the other small Persian Gulf states. It is all but impossible to be a soccer fan anywhere in the world and not know of Dubai and its airline, Emirates, which is a key sponsor of teams and has a major soccer stadium in London named after it. The Bahrain Rally, New York University-Abu Dhabi, and the planned Louvre Abu Dhabi are all meant to solidify respective reputations as havens for auto racing, culture and learning, and modernity and globalization. There are two unique forms of branding, however, that set Qatar apart from other regional actors and, in fact, from much of the rest of the world. One is the Al Jazeera satellite television station, and the other is diplomatic mediation and conflict resolution efforts.