Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (22 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

In fact, Steve eventually decided that giving recognition to the designers was a bad idea. Nowadays, Apple has abolished programmer names in the "About Box", and closely guards the names of their designers, allowing only a select few employees to interact with the press at all.

Steve Icon

by Andy Hertzfeld in February 1983

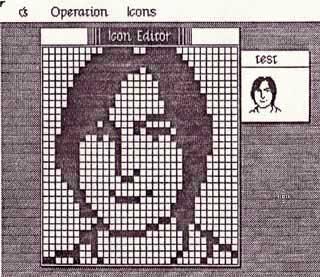

The Steve Jobs icon, by Susan Kare,

in the Icon Editor

In February 1983, I worked on putting together an icon editor for Susan Kare to use to create icons for the Finder. Inspired by the "Fat Bits" pixel editing mode that Bill Atkinson had recently added to MacPaint, it had a large window with a 32 by 32 grid, displaying each pixel at eight times its natural size, as well as a small window that showed the icon at its actual size. Clicking on a pixel would invert it, and subsequent dragging would propagate the change to the dragged over pixels.

Susan started working on icons for the Finder, but she also would draw lots of other images as well, for practice or just for fun, usually reflecting her whimsical sense of humor. One day, I came over to her cubicle to see what she was working on, and I was surprised to see her laboring over a tiny icon portrait of Steve Jobs.

Icons were only 32 by 32 black or white pixels, 1024 dots in total, and I didn't think it was possible to do a very good portrait in that tiny a space, but somehow Susan had succeeded in crafting an instantly recognizable likeness with a mischevious grin that captured a lot of Steve's personality. Everyone she showed it to liked it, even Steve himself.

Bill icon

Bill Atkinson was so impressed with the Steve icon that he asked Susan to do one of him, that he could use in the MacPaint about box. He sat in Susan's cubicle for an hour or so, chatting with her while she crafted his icon. I don't think it turned out quite as good as the Steve icon, but it certainly was an unmistakable likeness, and did become part of MacPaint.

At that point, It became a Mac team status symbol to be iconified by Susan. As soon as he saw Bill's icon, Burrell Smith started begging Susan for a Burrell icon, even though he had no specific use for it. He lobbied Susan for a few days, making his standard offer of best friendship (see

i'll be your best friend

), before she gave in and had him pose for his icon. Unfortunately, I can't find a copy of the Burrell icon to display here.

Susan did a few more portraits, for various members of the team who desired to be immortalized in a thousand dots. She'd usually work on them in the late afternoon, chatting with the subjects as they posed, while other team members listened in. I got to know a few of my teammates a lot better from these sessions.

Too Big For My Britches

by Andy Hertzfeld in February 1983

Apple's HR policy dictated that each employee was supposed to receive a performance review from their manager every six months, which helped to determine your salary increase or possibly an award of additional stock options. But as the end of 1982 approached, I hadn't received my review for more than eight months.

This wasn't very surprising, since Bob Belleville, who was my boss and our software manager, was not getting along very well with the software team. He thought that some of us were intrinsically unmanageable, and that we didn't sufficiently respect him. Bob had replaced Rod Holt as the overall engineering manager in August, responsible for both hardware and software, and had just hired a new software manager, Jerome Coonen, who was slated to begin in January, which would allow him to further distance himself from the software team. But he still had to deal with us directly one last time to write our reviews for 1982.

By the end of January, everyone on the team had received their review except for me. Others mentioned that Bob had acted somewhat strangely during their reviews, making cryptic remarks that they didn't understand, so I wasn't particularly looking forward to mine. I occasionally had to interact with Bob, but he was reticent around me, not saying much, seemingly hiding behind his enigmatic, tight-lipped smile. Finally, after another couple of weeks, Bob's secretary called me to arrange an appointment, presumably for my belated review.

The meeting was scheduled for 5pm, toward the end of the day on a Thursday afternoon in mid-February. Bob was waiting for me when I entered his corner cubicle. I asked him what was up. He said that he didn't want to get into it in the office, and suggested that we discuss it on a walk around the block. That was fine with me, but now I was even more apprehensive - generally, walks around the block were reserved for firing or demoting someone, or to talk someone into staying after they had quit.

Bob waited until we were a full block away from Bandley 4 before starting to speak.

"Well, Andy, you're not going to like hearing this, but you're a big problem on the software team and I'm giving you a negative review for the last six months of 1982."

I knew that Bob disliked me, but I was nevertheless shocked. I was working my heart out for the last two years, devoting my life to the Macintosh, seven days per week, holding the project together after Bud returned to medical school. I was really doing two full-time jobs, writing the Mac Toolbox in assembly language by night and helping everybody else by doing whatever was necessary each day.

"How can you say that?", I responded, horrified. "I accomplished everything that I was supposed to, and a lot more besides". All my previous reviews from Apple were extremely positive, including the last one from Bob, so this was new to me.

Bob unfurled his mirthless grin. "Oh, don't get me wrong, I think your technical work was perfectly adequate during the review period, and I don't have a single criticism of it. That's not your problem area. I don't have a single complaint with your technical work." He paused for a moment, to take a deep breath, and then continued.

"The problem is with your attitude, and your relationship with management. You are consistently insubordinate, and you don't have any respect for lines of authority. I think you are undermining everybody else on the software team. You are too big for your britches."

At this point, as he probably expected, I broke down into tears. The Macintosh was at the center of my life, and it was suddenly clear that I was going to have to quit. I couldn't work for somebody who was saying this, no matter how much the project mattered to me.

Perhaps Bob was a little taken aback by my tears, so he tried to soften things. "Listen, this could be a very expensive conversation. It could turn out to be either very good or very bad for both of us. I'm trying to get you to see how if you listen to me, things could turn out very good for both of us."

I had no idea what he was talking about, or how a bad review could possibly be good for me. "What do you mean, undermining the team?", I managed to choke out, "I'm always trying to help everybody else on the team. Give me one example of someone that I've undermined."

"Larry Kenyon", Bob replied. "You're stifling Larry Kenyon. Now he is someone with a good attitude, and you're keeping him from realizing his potential."

I always thought that I had gotten along great with Larry. I recruited him to the Mac team, after working with him on Apple II peripheral cards in 1980, and then handed off the low-level OS stuff to him while I worked on the Toolbox. I thought Larry was a terrific programmer and a great all around person, and treated him with the highest respect, and always enjoyed it when we worked together. I think I knew what Bob was getting at, though, as I had reacted poorly a few months ago when Bob appointed Larry as temporary manager when he had to be gone on a short trip, probably just to irk me.

By this point, I was crying harder, and Bob looked like he might start crying at any moment now, too. We were also pretty far from Bandley 4 by now, and it was starting to get dark. The tone of the conversation seemed to shift as we both realized that we should start heading back.

"This doesn't have to be that bad", Bob said as we turned around. "All you have to do is listen to me and things will work out fine."

"What do you mean?", I asked him.

"You need to show more respect to authority. It's not just me. Jerome is still new, and I'm afraid that you won't let him do his job. He's your boss now, and you need to show him respect, and let him do his job . But that's not the main problem. What you really have to do is stop talking to Steve Jobs." Bob paused and flinched slightly, as if just mentioning Steve was difficult for him.

"Whenever there's something that you don't like, even little things, you go running straight to Steve, and he interferes. I don't have any authority with the software team, because they always hear everything from Steve before I do, and he always hears everything about the software straight from you. It's making it so I can't do my job. You should communicate through the proper channels. I can't tell Steve what to do, but you work for me, so I can tell you."

I did respect Jerome, and I was trying to make an extra effort to support him as our manager, because I knew that we really needed him. Jerome was a very smart guy, and a passionate genius when it came to numerical software - I loved to hear him elucidate the intricacies of his beloved floating point routines. But I did consider him to be more of a partner than a boss, just like I did everyone else on the team, but I didn't think that he had a problem with that. But apparently Bob did.

But the Steve issue was different. From the earliest days of the project, Steve would usually show up at the Mac building in the late afternoon, or sometimes after dinner, and ask us about the happenings of the day. We would demo the latest stuff to him, or he'd complain about something, or sometimes we'd just exchange the latest gossip. After Bud went back to medical school, Burrell and I were the only ones who would regularly stay late, but after a while, more of the team began to hang out with us. It wasn't unusual for six or eight of us to go out for a late dinner, and then come back and keep working. By early 1983, most of the software team was staying late, and even some marketing and finance people would join us, but Bob Belleville never did, since he had to get home to his wife and two young daughters.

"I can't stop Steve from coming around", I told Bob. "If you don't want me to talk with Steve, you're going to have to tell him about it. I like Jerome, and I have no problem working with him, but now it looks like I have a problem working with you. If you think that I'm undermining the team, I'm out of here tomorrow."

Bob looked at me intently. "I don't have the power to fire you", he said. "You're going to give me power that I don't have if you quit. Do you really want to do that?"

By now, it was completely dark as we were approaching the Apple parking lot. We stopped in front of Bob's car.

"This could be a really expensive conversation for both of us", Bob muttered cryptically. "It's entirely up to you." With that, he got into his car and drove off, and I wandered back into Bandley 4, feeling stunned and drained. I got back to my cubicle, put my head down on the desk, and started crying again.

It was around 6:30pm now, and most of the software team was still around. Capps saw that I was upset, and asked me what was wrong. He began to get angry when I told him and a few others what happened, and he made me promise not to overreact until he had a chance to find out what was going on.

Larry Kenyon was still in his cubicle, so I went over and told him what Bob had said. I asked him to be honest, and to tell me if he thought I was stifling him in any way.

"You've got to be kidding!", Larry exclaimed. "I think it's really great working with you, that's the reason I'm on this team. I think it's an honor to work with you." With that, I burst into tears again, touched by Larry's support.

I was exhausted and confused, so I went home to get some sleep and to think about what I should do next. When I came in earlier than usual the next morning, there was a message on my desk to call Pat Sharp, Steve's secretary. She told me to come by his office right away because he wanted to talk with me as soon as possible.