Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (26 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

Kamoto-san looked confused but he got up from his seat and hurried into the dark janitorial closet. He had to stay there for five minutes or so until Steve departed and the coast was clear.

George and Larry apologized to Kamoto-san for their unusual request. "No problem. ", he replied, "But American business practices, they are very strange. Very strange."

As predicted, a few weeks later the Alps team came back with an eighteen month estimate for getting their drive into production, and we had to abandon the project. When Bob Belleville revealed that he and George had kept the Sony alternative alive, Steve swallowed his pride and thanked them for disobeying him and doing the right thing. The Sony drives eventually worked out great, and it's hard to imagine what the Mac would have been like without them today.

Saving Lives

by Andy Hertzfeld in August 1983

We always thought of the Macintosh as a fast computer, since its 68000 microprocessor was effectively 10 times faster than an Apple II, but our Achilles heel was the floppy disk. We had limited RAM, so it was often necessary to load data from the floppy, but there we were no faster than an Apple II. Once we had real applications going, it was clear the floppy disk was going to be a significant bottleneck.

One of the things that bothered Steve Jobs the most was the time that it took to boot when the Mac was first powered on. It could take a couple of minutes, or even more, to test memory, initialize the operating system, and load the Finder. One afternoon, Steve came up with an original way to motivate us to make it faster.

Larry Kenyon was the engineer working on the disk driver and file system. Steve came into his cubicle and started to exhort him. "The Macintosh boots too slowly. You've got to make it faster!"

Larry started to explain about some of the places where he thought that he could improve things, but Steve wasn't interested. He continued, "You know, I've been thinking about it. How many people are going to be using the Macintosh? A million? No, more than that. In a few years, I bet five million people will be booting up their Macintoshes at least once a day."

"Well, let's say you can shave 10 seconds off of the boot time. Multiply that by five million users and thats 50 million seconds, every single day. Over a year, that's probably dozens of lifetimes. So if you make it boot ten seconds faster, you've saved a dozen lives. That's really worth it, don't you think?"

We were pretty motivated to make the software go as fast as we could anyway, so I'm not sure if this pitch had much effect, but we thought it was pretty humorous, and we did manage to shave more than ten seconds off the boot time over the next couple of months.

Stolen From Apple

by Andy Hertzfeld in August 1983

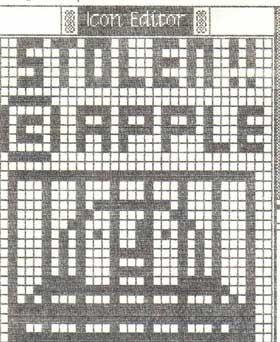

the secret "Stolen From Apple" icon

In 1980, a company called Franklin Computer produced a clone of the Apple II called the Franklin Ace, designed to run the same software. They copied almost every detail of the Apple II, including all of its ROM based software and all the documentation, and sold it at a lower price than Apple. We even found a place in the manual where they forgot to change "Apple" to "Ace". Apple was infuriated, and sued Franklin. They eventually won, and forced Franklin to withdraw the Ace from the market.

Even though Apple won the case, it was pretty scary for a while, and it wasn't clear until the end that the judge would rule in Apple's favor - Franklin argued that they had a right to copy the Apple II ROMs, since it was just a "functional mechanism" necessary for software compatibility. We anticipated that someone might try a similar trick with the Macintosh someday. If they were clever enough (which Franklin wasn't), they could disguise the code (say by systematically permuting some registers) so it wouldn't look that similar at the binary level. We thought that we better take some precautions.

Steve decided that if a company copied the Mac ROM into their computer, he would like to be able to do a demo during the trial, where he could type a few keystokes into an unmodified infringing machine, and have a large "Stolen From Apple" icon appear on its screen. The routines and data to accomplish that would have to be incorporated into our ROM in a stealthy fashion, so the cloners wouldn't know how to find or remove it.

It was tricky enough to be a fun project. Susan designed a nice "Stolen from Apple" icon, featuring prison bars. Steve Capps had recently come up with a simple scheme for compressing ROM-based icons to save space, so we compressed the icon using his technique, which not only reduced the overhead but also made it much harder to detect the icon. Finally, we wrote a tiny routine to decompress the icon, scale it up and display it on the screen. We hid it in the middle of some data tables, so it would be hard to spot when disassembling the ROM.

All you had to do to invoke it is enter the debugger and type a 6 digit hexadecimal address followed by a "G", which meant execute the routine at that address. We demoed it for Steve and he liked it. We were kind of hoping someone would copy the ROM just so we could show off our foresight.

As far as I know, no one ever did copy the ROM in a commercial project, so it wasn't really necessary, but it did create some intrigue for a while. We let it slip that there was a "stolen from Apple" icon hidden in there somewhere, partially to deter people from copying the ROM. At least one hacker became moderately obsessed with trying to find it.

Steve Jasik was the author of the MacNosy disassembler/debugger, which could be used to create pseudo-source for the ROM. He found out about the "stolen from Apple" icon pretty early on, and became determined to isolate it. He lived in Palo Alto, so I would occasionally bump into him, and he would ask me for hints or tell me his latest theory about how it was concealed, which was invariably wrong.

This went on for two or three years, before he finally cracked it: I ran into him and he had it nailed, telling me about the compressed icon and the address of the display routine. I congratulated him, but was never sure if he figured it out himself or if someone with access to the source code told him.

Pirate Flag

by Andy Hertzfeld in August 1983

The pirate flag, as posed for Fortune Magazine in 1984.

The Mac team held another off-site retreat in Carmel in January 1983, just after the Lisa introduction (see

credit where due

). Steve Jobs began the retreat with three "Sayings from Chairman Jobs", intended to inspire the team and set the tone for the meeting. The sayings were:

1. Real artists ship.

2. It's better to be a pirate than join the navy.

3. Mac in a book by 1986.

I think the "pirates" remark addressed the feeling among some of the earlier team members that the Mac group was getting too large and bureaucratic. We had started out as a rebellious skunkworks, much like Apple itself, and Steve wanted us to preserve our original spirit even as we were growing more like the Navy every day.

In fact, we were growing so fast that we needed to move again. In August of 1983, we moved across the street to a larger building that was unimaginatively designated "Bandley 3". I had worked there before, in 1980, when Apple had initially built it to house the original engineering organization. But now it was to be the new home of the newly christened "Macintosh Division", over 80 employees strong.

The building looked pretty much like every other Apple building, so we wanted to do something to make it look like we belonged there. Steve Capps, the heroic programmer who had switched over from the Lisa team just in time for the January retreat, had a flash of inspiration: if the Mac team was a band of pirates, the building should fly a pirate flag.

A few days before we moved into the new building, Capps bought some black cloth and sewed it into a flag. He asked Susan Kare to paint a big skull and crossbones in white at the center. The final touch was the requisite eye-patch, rendered by a large, rainbow-colored Apple logo decal. We wanted to have the flag flying over the building early Monday morning, the first day of occupancy, so the plan was to install it late Sunday evening.

Capps had already made a few exploratory forays onto the roof during the weekend while a few of us looked out for guards on the ground. At first, he thought he could just drape the flag on the roof, but that proved impractical as it was too hard to see, especially when the wind curled it up. After a bit of searching, he found a thin metal pole among the remaining construction materials still scattered inside the building, that was suitable to serve as a flag pole.

Finally, on Sunday night around 10pm, it was time to hoist the Jolly Roger. Capps climbed onto the roof while we stood guard below. He wasn't sure how he would attach the flag, and didn't have many tools with him. He scoured the surface of the roof and found three or four long, rusty nails, which he was able to use to secure the flag pole to a groove in the roof, ready to greet the Mac team members as they entered the new building the next morning.

We weren't sure how everyone would react to the flag, especially Steve Jobs, but Steve and almost everyone else loved it, so it became a permanent fixture of the building. It usually made me smile when I caught a glimpse of it as I came to work in the morning.

The flag waved proudly over Bandley 3 for about a month or two, but one morning in late September or early October, I noticed that it was gone. It turns out that the Lisa team, with whom we had a mostly friendly rivalry, decided it would be fun to steal the flag for themselves. I think they sent us a ransom note or something, so a few of us stormed over to the Lisa building to retrieve it, which we accomplished, although Capps had to wrestle it from the grasp of one of the secretaries, who was hiding it in her desk.

The flag continued to fly over Bandley 3 for more than a year. I think it was even photographed for a magazine or two during the Mac introduction. But suddenly one day it was missing again, and I'm not sure if anyone knows what happened to it. It would be a great artifact for the Computer History Museum if it ever turns up.

Close Encounters of the Steve Kind

by Tom Zito in September 1983

Steve had managed to get Don Knuth, the legendary Stanford professor of computer science, to give a lunchtime lecture to the Mac team. Knuth is the author of at least a dozen books, including the massive and somewhat impenetrable trilogy "The Art of Computer Programming." (For an amusing look at Knuth's heady self image, and his $2.56 reward program, see

http//www-cs-faculty.stanford.edu/~knuth/books.html

)

I was sitting in Steve's office when Lynn Takahashi, Steve's assistant, announced Knuth's arrival. Steve bounced out of his chair, bounded over to the door and extended a welcoming hand.

"It's a pleasure to meet you, Professor Knuth," Steve said. "I've read all of your books."

"You're full of shit," Knuth responded.

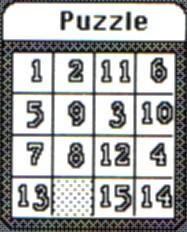

The Puzzle

by Andy Hertzfeld in September 1983