Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (30 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

Bill Atkinson came up with the idea of defining a system flag called "MonkeyLives" (pronounced with a short "i" but often mispronounced with a long one), that indicated when the Monkey was running. The flag allowed MacPaint and other applications to test for the presence of the Monkey and disable the quit command while it was running, as well as other areas they wanted the Monkey to avoid. This allowed the Monkey to run all night, or even longer, driving the application through every possible situation.

We kept our system flags in an area of very low memory reserved for the system globals, starting at address 256 ($100 in hexadecimal), since the first 256 bytes were used as a scratch area. The very first slot in the system globals area, address 256, had just been freed up, so that's where we put the MonkeyLives boolean. The Monkey itself eventually faded into relative obscurity, as the 512K Macintosh eased the memory pressure, but its memory was kept alive by the curious name of the very first value defined in the system globals area.

90 Hours A Week And Loving It!

by Andy Hertzfeld in October 1983

Burrell wearing the sweatshirt

Most of the Macintosh software team members were between twenty and thirty years old, and with few family obligations to distract us, we were used to working long hours. We were passionate about the project and willing to more or less subordinate the rest of our lives to it, at least for a while. As pressure mounted to finish the software in time to meet our January 1984 deadline, we began to work longer and longer hours. By the fall of 1983, it wasn't unusual to find most of the software team in their cubicles on any given evening, week day or not, still tapping away at their keyboards at 11pm or even later.

The rest of the Macintosh team, which had now swelled to almost a hundred people, nearing the limit that Steve Jobs swore we would never exceed, tended to work more traditional hours, but as our deadline loomed, many of them began to stay late as well to help us test the software during evening testing marathons. Food was brought in as a majority of the team stayed late to help put the software through its paces, competing to see who could find the most bugs, of which there were still plenty, even as the weeks wore on.

Rear View of the Sweatshirt

Debi Coleman's finance team decided to commemorate the effort that the entire team was putting forth in the traditional Silicon Valley manner: they made a T-Shirt. Actually, to make it a little more special, they chose a high quality, gray hooded sweatshirt. Steve Jobs had recently bragged to the press that the Macintosh team was working "90 hours a week". They decided that the tag line for the sweatshirt should be "90 Hours A Week And Loving It", in honor of Steve's exaggerated assertion.

The sweatshirt featured the name Macintosh in red letters, purposefully misspelled as "Mackintosh", as it had been in a recent article, with a black squiggle crossing out the errant 'k'. The "90 Hours" tag line was emblazoned in black across the back. They were produced in time for the next testing marathon, as a reward for participating. The software team wasn't all that pleased, since we felt that we really were working that hard, but most of the other sweatshirt recipients weren't even coming close. But it was a pretty nice sweatshirt, so lots of the engineers started wearing them frequently, including Burrell Smith.

When Burrell finally quit Apple in February 1985, he continued to wear the sweatshirt almost every day, but, as soon as he returned home following his resignation, he took some masking tape and made a big 'X' across the leading '9' character, virtually obliterating it from view. He proudly displayed the updated motto, reflecting exactly how he felt. It now read "0 Hours A Week And Loving It".

The Mythical Man Year

by Andy Hertzfeld in October 1983

Bill and Burrell on the

cover of Byte

One of our first encounters with the press was a group interview with Byte magazine in October 1983. We wanted an article to come out concurrently with the Mac intro the third week of January, and Byte had a three month lead time, so they were the first.

Byte was one of the first PC hobbyist magazines, written for a fairly technical audience of computer enthusiasts. Five or six of us were being extensively quizzed by two Byte editors, including Steve Jobs. We were talking about the Mac's graphical user interface software, and how long it took to develop.

Quickdraw, the amazing graphics package written entirely by Bill Atkinson, was at the heart of both Lisa and Macintosh. "How many man-years did it take to write QuickDraw?", the Byte magazine reporter asked Steve.

Steve turned to look at Bill. "Bill, how long did you spend writing Quickdraw?"

"Well, I worked on it on and off for four years", Bill replied.

Steve paused for a beat and then turned back to the Byte reporter. "Twenty-four man-years. We invested twenty-four man-years in QuickDraw."

Obviously, Steve figured that one Atkinson year equaled six man years, which may have been a modest estimate.

MacPaint Gallery

by Andy Hertzfeld in October 1983

Bill Atkinson began writing MacPaint in February 1983, just after Susan Kare joined the Mac team to design bitmaps for fonts and icons. Susan became one of the first and most accomplished users of MacPaint, trying out new features as they were developed and using it for a wide range of practical applications.

Susan kept a notebook of many of the MacPaint documents that she created as the Mac team struggled to finish the Macintosh throughout 1983. They provide an interesting glimpse of the daily life of the Mac team during that period. I'm pleased to be able to present scans her beautiful drawings here as part of Macintosh Folklore.

You can click on an image to see a larger rendition of it; use the back button to return to the story.

The image on the left is an annoucement of a combined birthday party for seven Mac team members whose birthday was in early April, including myself, who was terrified of turning 30 at the time. As a birthday gift, Susan made a jersey for me with a large hexadecimal number "1E" (which is 30 in base 16) on it, so I could still say I was a teenager, at least in hexadecimal.

The image on the right is for picnic held in July to celebrate the wedding of two members of the software team: programmer Larry Kenyon and librarian Patti King. Larry and Patti actually eloped in June; the picnic happened after they returned from their honeymoon.

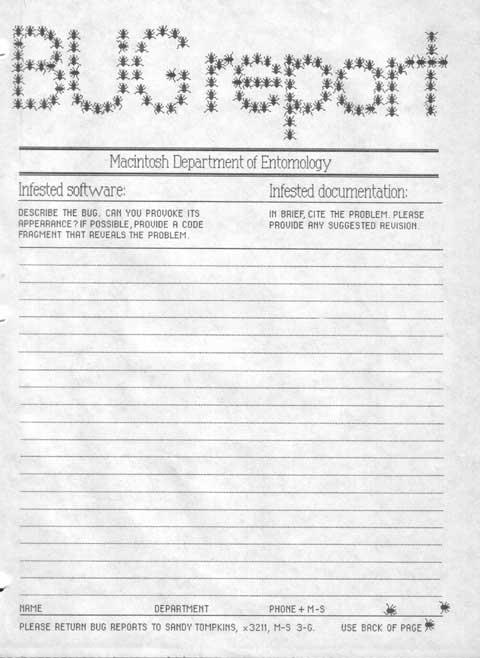

One of the most important activities during the last couple of months before shipping was software testing. We held some testing marathons, where the software team enticed employees from the rest of the division to stay late and help test the software by bribing them with dinner (see

90 hours a week and loving it

). The image on the left is an announcement of another bug hunt, and the one on the right is a bug report form that was used during the testing.