Riding Barranca (17 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

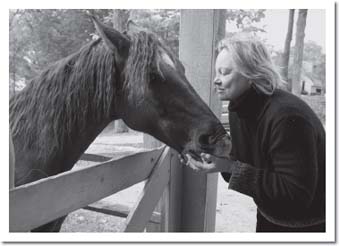

When I get back to the house, I give Helen a call, and she offers to let me borrow Bendajo as a companion horse. How

wonderful to have an understanding cousin close by. Tonka is thrilled to see a pal arrive, and I am also grateful.

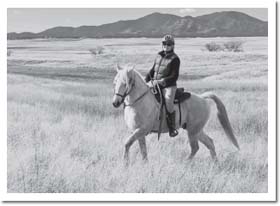

Ocotillo Trail

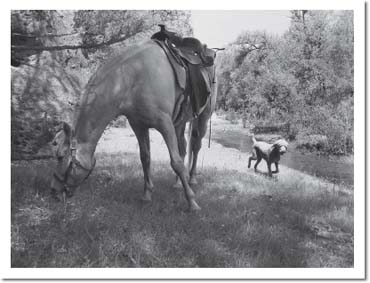

There is nothing nicer than riding alone on a good horse with a faithful, quiet dog beside you. Bali is a good followerâhe instinctively understands the path, and it is a joy to watch him exploring, submerging in the water and then trotting ahead. Here on the Sonoita Creek, I am beginning to feel the heart-tug of departure, soon to leave my beloved Southwest. Tonka is cooperating exceptionally well today, as if he senses he is now my “Number One Horse,” and his big-horse-ego likes thatâhe is responding with great athleticism as well as sweetness.

Tonka also wins the award for the most

poops

per ride. Inevitably he lets loose in the trailer, and I have to kick it out with my boot, but then, out on the trail, he will stop and do his

duty seven or eight more times. I figure, better here than in the paddock. I don't know if he is just a “Nervous Nelly,” or if he has an exceptionally good digestive system, but right on schedule, he stops and takes another dump.

The ocotillo is now in full flaring bloom, but many of the other wildflowers have passed, with the exception of the “fried egg in the pan” white blooms of the prickly poppy. Their tissue-thin blossoms rest on top of their thistles all along the trail. Nature has its rhythm, as if she didn't want us to go without a visual treat for longâalways something orchestrated to entertain the eye.

By Sonoita Creek

Tonka is quite familiar with this trail by now, and we move along smoothly until we descend into the creek and our path is blocked by an enormous bull, his massive balls hanging down like gunpowder sacks. But this old fellow is rather

sedentary. Perhaps he is a bit of a “Ferdinand” as he munches on fresh green cottonwood leaves, not paying us much attention.

We skirt around him and ride on out to the Indian cave where we normally stop for lunch. It is still early, only 11:30

A.M.,

but I don't want to tire my dog. So we cross the creek and settle down in the shade, a perfect place to take a break. Tonka is treated to riverside grass, and Bali wanders about in the stream to cool his feet, while I eat my salami-and-cheese sandwich and drink a mango smoothie. The day is dazzling, and the greenery surrounding the creek is a pleasure. I could stay here for hours.

Heading back, I notice how Tonka is always aware of any unusual creature before I amâhe makes a miniscule halt and swerves when he sees a coyote standing down below in the running stream. As two separate creatures, we observe each other. And then a hundred yards up the path, I hear a rustling in the leaves and a six-foot-long, red coachwhip snake wriggles up onto the canyon wall. I begin to keep an eye out for rattlers, as the midday heat has increased, and soon they will be a real presence. Little lizards run about on the ground and up the canyon walls. A little further on, Tonka shies when a wild turkey bolts from the underbrush. “Gee,” I say out loud, “we're seeing everything today,” including some white-tailed deer that bound across the path up ahead.

When we return to the barn, I give Tonka a bath, shampooing his mane and tail. Then I leave him tied to the rail to dry. I offer him a drink from the upright hose and he slurps it up as if it were a bubbler.

Last Ride

Goodbye to the Patagonias. Goodbye to the grey-green, burnt-out grasslands that stretch all the way to Mexico. Goodbye to the transients and the burlap bales dropped along the roadside. Goodbye to the border patrol in their dusty white vans with green stripes. Goodbye to the grand Huachucas. Goodbye to Saddle Mountain, and Indianhead, too, peeking out behind. Goodbye to Red Mountain, that majestic, muscular presence. Goodbye to the border fence with all its problems. Goodbye to the red earthen roads, the desert

agave,

and the stunted oaks that endure the persisting winds. Goodbye to the arid skies, to undisturbed moonlight and brilliant stars. Goodbye to the Herefords huddled by the water tank. Goodbye to barbed wire and those treacherous cattle guards. Goodbye to the lone coyote and the screeching hawk wheeling overhead. Goodbye to this clean sweep of vista that always extends my soulâgoodbye Arizona, goodbyeâ

until we meet again.

Love Boat

We leave Patagonia, and head up to Scottsdale to say goodbye to my mother. She is now in a rehabilitation facility, but it has become quite clear to my sister, who has just flown in from Wisconsin, that Mom is not going to recover. Our niece, Daphne, is also there and when she tells Gramma they are going to have to move her, Mom says softly, “No hospital, home.”

After conferring with the doctors, Cia decides to Med-Vac Mom back to Oconomowoc. The godsend is that she will never have to go into a nursing facility, or live through the terrible end-stage of Alzheimer's.

Years before, in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, I was with my mother during her first bad hallucination episode. Even though it was way past midnight, my mother was wide awake. She thought that she

had been watching a movieâit had been like a waking nightmare.

“There were people all over the room,” she said, “hoards of them, Muslims and blacks. And then I was in the cockpit of some Army plane, flying over a place like Siberia. It was so wintry and cold, and there were battleships and rooms and rooms of brothels, with men doing things to each other, beating up women, hurting small children. It was terrible, so icy and cold, and then there was this palatial hotel where they had everything you could ever want, crocodile bags that would normally cost $3,000 were only about $700, and linens you would not believeâeverything, so many luxuries!” It sounded like a vision of hell.

“There's a man standing behind you!” she pointed. “He's ugly with wild red hair and pock marks all over his face. Tell him to get out of here!” She was so convincing, I swung around to look. “And there are children peeling the wallpaper! Why are they doing that? Daphne is destroying the lampshade. Tell her to stop it! Why are there so many people in my room? They are being very rude, sticking their tongues out.”

“Your mind is just playing tricks on you, Mom.”

“Don't lie to me! I know what I'm seeing. And there's water streaming down the walls, look.” She held out her hand as if she could feel it. “And what is this tissueâit's falling from the ceiling.” I looked in her hand as if I could see it too, but of course there was nothing there.

Mom insisted that there were women in the closet stealing Popi's clothing.

“No, there aren't any women,” I said.

“I know what I see!”

“Okay, let's get up and go over there.” I helped her get out of bed and led her over. She looked perplexed, rattling through my father's naked wooden hangers. She agreed that the women

had left. At least they weren't sitting in Bluebeard's closet with pools of clotted blood.

“Let me rub your feet,” I suggested, trying to soothe her with the rose-scented oil I'd brought from home. I sang her the songs that she used to sing to me in my childhood, “Summertime” and “Mighty Like a Rose.” In a pathetic little voice, she tried to sing along with me, sometimes leaning up on her elbow to see what else was going on.

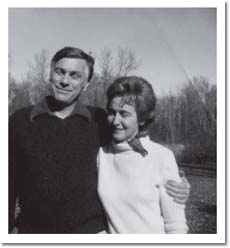

Mom and Dad

The next morning, downstairs, Mom's hallucinations continuedâ“There are those same children, standing in the hallway, with a big tall black man. What do you think they want?” She motioned them in, waving with her hand, with an endearing, welcoming expression on her face.

Mom insisted that this was not her home, and she wanted to get in the car with Wanda and go back home immediately. “I don't like this hotel,” she said.

“This isn't a hotel,” I assured her. “You're staying in your own house, Broadoaks.” I encouraged her to come outside and sit down on the lawn chair beneath the pergola, before her round English garden.

Often, in the past, she and Wanda could be seen here weeding, or planting, side-by-side, both of them in broad, straw hats.

“Let me read you a story,” I said to her and she nodded her head, content for a moment. It was nice reading out loud to my mother. I liked this reversal, taking care of her, but soon the hallucinations took hold again. “Why are those children destroying my plants?”

“They aren't destroying anything. You're seeing things.”

“They're using clippers. They're tearing at the flowers with scissors. Why are they doing that?”

“Just close your eyes and listen.”

As I read, she began to calm down. She told me that my story was, “Very well written. You are an excellent writer.” She had always said that. She had always been supportive of me in that realm, even when I was ten years old and read her each new chapter from “Betsy and Pixie Ride Again,” my first handwritten book, composed on a notepad of yellow paper.