Riding Barranca (18 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

She wanted iced tea, and Wanda brought her a full tumbler. “Wanda knows how to do everything.” Mom was more dependent on Wanda than on any of us.

At odd moments, Mom seemed lucid, and continued to surprise meâcoming around a corner like a burst of sunlight emerging from a cloud, only to open her arms and beamâ“You know I love you, Laura.”

Lost on a sea of forgetfulness, she could still touch bottom sometimes. I felt more like a shipwrecked person. How easily people say itâI love you, I love youâ¦just tossed off. How rarely it's said with true feeling.

I thought of my mother, my father's wife, who wrote love letters to him overseas, day after day, full of passion, always unwavering. She only thought the best of him now. “He was such a wonderful husband,” even if she couldn't remember his name. “He was always so much fun.”

“You had your difficult times,” I reminded her.

“Really, I don't remember that, when?”

“Oh, when he'd go off riding with other people.”

“Oh yes,” she laughed, “he did do that.” She no longer seemed to care.

When my father was asked, “What was the most fortunate thing that ever happened to you?” he answered, “Marrying my wife.”

Conflicted, unsure, often secretive, I was my father's daughterâgrandiose, yet somehow dwarfed. Was I standing in for him now? I would send my mother lilies and chocolate. I could forgive her jealous heart. Still, at least, I could say it, right? “I love you too, Mom,” and mean it. I could come around, and embrace her, finally receiving her love.

On saying goodbye to my mother for what would be the last time, I consider forgiving her for not being a very good mother, but instead, I apologize for not always being a good daughter. She accepts that. We have reconciled over the years since my father's death, but I still can't conjure up the emotions you're supposed to feel when your mother is dying. I feel rather empty.

It is a short five-hour flight to Newark, and soon we are picked up by our trusty driver and are off to the Berkshires.

As we go, I feel disoriented. The landscape hurts my eyesâ

too green.

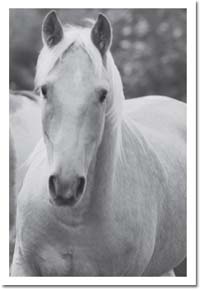

Everything looks too close, not enough space. It is hot and humid. But when we pull in our driveway, I am happy to see Barranca, Peanut, and Rocket out in their enormous field. Do they know how lucky they are? And how little they would have to graze upon if they were still in Arizona?

I don't ride on the first day back but wait until the following morning to saddle up Barranca. I take him out on the familiar trails behind the house. We have miles and miles of trails hereâmost of them on our neighbor's lumber landâbut many trees have fallen across the paths during the course of the winter, and I am annoyed by all the blockages. We work our way around the debris and head down to Long Pond. But I still don't feel like I'm “home.” The lilacs are out in abundance, dripping with moisture, and Barranca moves out beautifully, but I am in an off-mood, not even entranced by the wild lavender phlox that is springing up along the trails.

The next morning, I take Peanut out for a go, and he surprises me with his willing, fast walk. I treat his mouth with utmost gentleness. The trick will be teaching others how to handle him so that he doesn't get confused or sour from varied communications.

Meanwhile, my sister and I exchange emails and phone calls about our mother, back in Wisconsin. One day, she seems to be doing fine, and the next, she barely opens her eyes. She is in a comfortable hospital bed, facing the lake, and seems content for the most part. She still seems to recognize people, and beams at Mary Read, my cousin's wife, one of her favorites, though when my brother David arrives, she asks, “Are you mine?”

Arizona Muse

Baldwin Hill Farm, just fifteen minutes away, is another world of wide open fields on top of a gentle rise. This is where we first lived when we came to the Berkshires, when Ayler was only two years old. We rented the Burdsall farmhouse with its four-hundred acres, and I rode all over this hill with Bunny Kirchner, an eighty-year-old, mad-for-horses local man. I know the trails here well.

During Bunny's last few years, he lived in an ambulance. Whenever we dropped by his emergency vehicle, it was disturbing to see the deep trash on the floor. Sometimes, when I sent Ayler in to deliver food, he was afraid that Bunny was dead. But Bunny lived into his nineties, and kept on riding right up to the end. Horses were his passion.

Bunny was an old-timer who knew everything about every family who lived along the road. But he often did things in a strange manner, like using a knife to cut a slit in my girth,

rather than using a hole-punch. One day when I was riding his stallion and we took off at a gallop, the burst of energy straining against the leather made the girth snap, and I went flying, banging my head on the hard gravel road. Now I always wear a helmet.

My young friend, Arizona Muse, and I proceed to the crossroads on Baldwin Hill and follow the tractor trails that go from one field to the next to the next. There is a sweet expansiveness up here that one does not feel in the closed-in forest

âit lifts my spirits.

Now that Arizona's baby Nikko is getting older, she is considering getting back into modeling. At twenty-one, she thinks she is too old, but her agency, NEXT, is thrilled to have her return. She has her willowy figure back and a lot of jobs seem to be coming her way. I tell her to watch out and not scratch her face. Arizona is so beautiful, it is almost difficult to take her inâa natural perfection that is dazzling, and yet she seems grounded, confident, and very assured for someone so young.

We ride up to the little Egremont Cemetery and down the dump road until we find an opening into another set of fields. Now, we ride quietly and just take all of this in. So often, it is better not to talk on horseback but to try and remain in touch with what is happening with your horse, how the bit feels in his mouth, how he is walking on the pathâgiving leg signals and making subtle moves.

Arizona and I both appreciate the great silence that surrounds us.

She is getting the hang of the four-beat gait, and is a lot more relaxed about her son, who is now with her mother, Davina. Last year, while Arizona was still nursing, she paid

more attention to the clock when we rode. The tug of the mother-nursing-baby bond was always there, putting her on remote alert, but now neither of us wears a watch, for we are in a timeless zone of pure pleasure.

Rocket Man

I ride Barranca alone through the woods and then up the Sarsaparilla Highway. This woodland trail is surrounded by thin, dark-skinned, birch-like trees, and if you break off a twig and give it a chew, it tastes vaguely like root beer. Climbing the narrow switchback trail, we head to the top of the mountain, zigzagging back and forthâgood for the horses' haunches.

While I ride, I think about my mother at my sister's house in Wisconsin and wonder if I should go out there. Cia assures me that I don't need to come. The hospice workers have said that Mom only has another day or two to live. That is hard to believe. I keep wondering when I will feel something.

Elizabeth Beautyman

Last night, I woke three times gasping for air, a kind of sleep apnea I rarely experience. The second time, I felt a dark brown presence by my bed, which I struck out at with my hand. Turning on the light, getting my wind back, I wondered if it related to my mother's struggle for oxygen, as she had

begun “Cheyne-Stokes” breathing. Was this a visitation of some sort?

It is raining this morning when I awake so I figure that my ride with Elizabeth will be cancelled. But she calls and says that she is still game to go out, so we decide to take our chances. The rain does let up, but the wind through the leaves sends showers down upon us. When I break a branch overhead and she gets sprayed, she yells out,

“Hey!”

Don't do that.

“Sorry,” I answer. It is a compulsive habit I have, always clearing the trails overhead, snapping branches. Helen's ex-husband, the psychologist, liked to say that breaking branches indicated anger. Helen and I always laughed over that, snapping away.

I take Elizabeth down to Long Pond. The trail is slippery going downhillâwe leave horse-hoof skid marks all along the way. Once we are on solid ground, we enjoy a few good canters, and she gets the feel for Peanut's moves. It is a stormy morning with thundershowers coming and going, but that only adds to our excitement

âall those negative ions.

That evening, I hear one of the horses ringing the tall standing bell by the corral. I assume it is Peanut, my trickster. Horses have an innate sense of timing and love a regular schedule. I guess it is time to walk them down to their field for the evening. Rising from the comfortable love seat, I hear the phone ring. It is my sister. Quietly she says, “Mom just went. You were my first call.”

I sit on the love seat in silence, thinking of what Phil Caputo said after his father died last winter, how it was like looking up at a familiar landscape and the mountain that had always been there, was suddenly gone.

Alford Brook

With the sun shining through the clouds, the air is at that perfect temperature. I ride Barranca out into the fields, which exude such a sweet smell of earth and grass, I feel intoxicated. We wade through the Alford Brook, climbing up a bank, proceeding uphill into more open pasture.

A few years ago, my horse Nashotah balked when I urged him into this field, but I made him move forward. And then, I saw a big black dog at a distance and yelled out, “Go

on, big dog, go home.”

But the “big dog” stood up on its hind legs. It was a BEAR! No wonder Nashotah had almost refused to enter this field, for bears have a very pungent smell, like rotting meat, quite unpleasant to horses. Luckily, we got out of there before Nashotah took the bit in his mouth and bolted.