Riding Barranca (7 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

There are many inviting pastures up here that level out as we go. Clearly, this road has not been traveled by truck in quite some time, but we are able to follow the trail and keep wending our way around obstacles. The chartreuse lichen is particularly vibrant on the tall rock face. From this height, we can see all the surrounding mountains covered with snowâ

sun on snow,

such a brilliant combination.

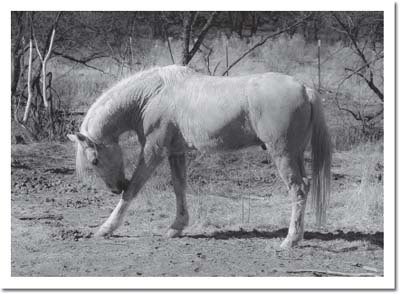

On the way down, I spot the old white horse that the Turners have turned out alone on this land. He is so old and wasted he doesn't even move when he sees us. Barranca is interested in what this white horse is all about, but even

as we approach him, the horse stands stock still. I worry that perhaps he is not getting enough food and water up here. Horses like to have at least one companion, and this poor old guy is a lonely sight.

Tonka Waken

I have an afternoon ride planned with Helen but run into Patagonia first to go to the post office. I see Miguel Fuentes, who helps supply our firewood. One time he was helping me clean up the wood pile when a pack rat ran up my sweatpants! We always have a good laugh over

la rata.

I ask Miguel if he would be willing to do some

trabajo, dos horas, con caballos, ahora,”

and he says,

“Si.”

I don't

really speak Spanish and he doesn't understand English, but somehow we communicate, I think.

I need help forking up the old, wet hay embedded in the mud around the feeder. But Miguel doesn't show up on time, so perhaps he misunderstood me. Helen and I wait a bit more, then take off for Guajolote (turkey) Flats. The trails here go up high into the Patagonia Mountains. As we climb, we look down on Soldier's Basin where we see a border patrol SUV on a distant red clay road cut into the mountain. We wave. Do they have their binoculars trained on us? I wonder if we look dangerous.

Today, we are seeking out an old mesquite corral that is somewhere up in this direction. Passing through three gates, we finally have the option of bearing right or going down a steep bumpy road to the left. My memory tells meâ

leftâ

and soon we find it. Leading the horses into this broken-down enclosure we think about camping out up hereâwhat fun we would have together.

On family vacations, Helen and I often went riding in the most unusual places, whether it was on the beaches of Mexico or looking for elephants in Kenya. A family trip was not a proper adventure without a horseback ride, and it was a great way for the members of our boisterous, athletic family to be together.

Helen's father, my Uncle Billy, still liked to ride, and owned several Icelandic horses in Vermont, while Popi was in charge of the family stable in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. It held a motley crew of llamas and Thoroughbreds, purchased off the track, (obviously not winners). There was not one truly sound and steady horse amongst them. People often offered him their rejects, for he never looked a gift horse in the mouth. He did have one or two personal favorites, and Merlin was one of them.

Once when he wanted to give me a piece of jewelry he'd purchased in Tuscany, he took me into the stall of this dappled Arabian, a horse I considered too small for my dad. There around Merlin's neck hung a golden chain with lapis stones. For a moment, I thought he was getting queer for this horse, but no, it was actually a necklace for me.

In the winter Popi rode out in Carefree, Arizona, and he liked to joke that his chestnut gelding had saved his life. On an all-day ride in the desert, my dad had collapsed from heat prostration and had to be collected by helicopter. When they took him to the clinic, the doctors discovered that he was anemic. The anemia led the doctors in Milwaukee to detect esophageal cancer in its earliest stages. Thanks to this riding mishap, a successful operation, and subsequent radiation, he was able to live another six years.

Even after radiation treatment, losing close to eighty pounds, he kept on riding. He rode days before he was taken into intensive care. He rode right up to the pearly gates, I suppose. Don't worry, Dad, we'll take care of Mom and your horses. I wonder where he's riding now.

Helen and I look out over the San Rafael Valley in the distance and feel like we are on top of the world. Few people know the land around here as well as we do, having ridden over so much of this landscape. Today, I feel especially intimate with this great expanse. Our dogs follow nicely, scooting in and out of the red-barked manzanita, which flourishes up at this altitude.

Helen points out the deep grinding hum of a drone somewhere out of sight. These are unmanned glider planes, controlled from Sierra Vista, looking for drug runners and other transients. “Why can't they use mufflers on those

things?” Helen protests. We agree that the drone creates an unfortunate noise in this otherwise peaceful terrain. Often we ride in deep silence.

On our way home, every vehicle that passes us on the road is a border patrol van. Three BP men all dressed in green are having a bit of a break by the roadside. Helen stops the truck to chat and asks if there has been much activity in the area. “Yeah, we're always busy,” one responds. But they don't look too busy at the moment.

By the time we get back to the corral, Miguel is there working away and I join him. He has already gathered up most of the old rotten hay, and we finish cleaning up together. Most people out West don't bother with manure, letting it dry up and blow away, but we are making compost. I remove three

cholla

plants, which could be potential hazards. Miguel wonders if I'd like a bottle of

bacanora,

tequila moonshine, and it seems like the perfect gift for Clovis when we go to visit him in Australia.

In Town

Fifteen months ago, Hurricane Norbert swept over this colonial town dropping twenty-seven inches of rain on the already saturated mountains. Three major mudslides were released, bringing a torrent of muddy water through Alamos, sweeping cars aside, destroying bridges, taking out roads and electricity and leaving the beautiful

Hacienda de los Santos

knee-deep in mud. But even worse, the poor people in the lower land were devastated, often trapped in their adobe homes, holding babies over their heads as the waters mounted.

Now, as Erma Duran and I drive into town, everything looks relatively normal. The lush hillsides of Alamos are

covered with the bright magenta blossoms of the

amapa

trees, which are always blooming this time of year when we come down for the annual music festival. It has taken eight hours to get here, and we are eager to unload our bags and settle in.

The next day, my friend Erma goes to work on one of the hacienda's antique wooden statues. Erma has done restoration work all over the world, and she is scheduled to restore the hacienda's little theater with Venetian plaster and stenciling.

That morning, I meet up with an American woman named Linda on the outskirts of town, and follow her pickup to the corral at the end of a twisting maze of unpaved roads. Linda Knieval Damesworth is related to the famous motorcyclist, Evel Knieval, and I wonder if she has some of the same death-defying genes.

I get out my own saddle and pad, as many Mexican saddles have stirrups that are far too short for me, and my Western saddle seems to fit this little mare, Rayulita, perfectly. She is part Arab, and her five-month-old colt is a smart-looking dun, but he will have to stay behind with the other horses as we ride up the cobbled streets on the far side of the wash, waving to the local children who gaze at us from their well-swept yards.

Continuing out into the foothills, Linda points out the

palo santo

trees, which are now bare, a grey-barked tree with white saucer-like flowers that are sweet and succulent. “Hunters often position themselves near these trees because the blossoms draw the animals,” she explains.

We jog on down a small dirt road, passing the entrance to

Rancho Palomar.

Linda mentions that many hunters go there to shoot quail and dove, and the chef then cooks them up. The road continues with fragrant, wet sage growing

on either side. As we wind up into the higher hills, there is a gradual incline, and I suggest we try a canter.

Rayulita takes off. I can tell she is not used to an easy lope but likes to flat-out run. Her gait is a bit choppy, and I have to hold myself down in the saddle as we leave Linda and her horse behind. At the top of the hill, I wait for her to join us. The air smells freshâthey had quite a bit of winter rainfall the previous weekâand I wonder if that will be a problem on our ride over the Alamos Mountains scheduled for the following day.

Big, dark clouds are building, and the lights of Alamos are coming on in the distance. If it rains again tonight, the ride might be called off. Linda thinks that the five-hour ride to

El Promontorio

is a bit arduousâthere is a lot of climbing over slick rock and rubble to get to the old mining site.

In 1683, silver mines were discovered here by the Spaniards, and by 1790, mining was at its peak. Alamos produced more silver during this period than any other place in the world. Now new mines are starting back up, which pleases the local Mexicans as that means jobs, a much different attitude than we have in southern Arizona.

On the way back, the sky continues to darken. Rayulita shows me how fast she can walk, eager to get back to her nursing colt. She is a very responsive little mare. I hope I can go out on her again.

I thank Linda and head back into town to join Erma for dinner. Then we race across the street to the opera. Afterward, the crowd spills out onto the cobbled streets where we spot Ramon and his patient white donkey, Gaspar, loaded down with casks of red wine. The young people follow the

estudiantina

singers, decked out in their traditional beribboned costumes. Meandering around the streets of Alamos, the

crowd sings along with the instruments, helping themselves to free wine, a very festive tradition.

When we retire for the evening, music still fills the streets from a distance. I want to get a good night's sleep before tomorrow's long ride. I keep hearing warnings about

El Promontorio,

often including the word,

peligrosa

(dangerous), and I'm a little wary as I sit outside in the courtyard and watch the lightning in the Alamos Mountains high above. A light rain begins to fallâgood for sleepâbut will it make the trails too slippery? While the town is now clean, out celebrating, cat-claw tracks from the recent mudslides are still scarring the mountains as if embedded in natural history.

Whoa!

This morning is dry and clear, perfect weather for riding, though I have been warned that it could be very cold up in the mountains, especially if we ride into the clouds. I take along multiple layers when we go over to the Red Door for breakfast.

Teri Arnold, the owner of

La Puerta Roja,

has organized our adventure. Another friend of hers, Rosemary Kovatch, will join us. She is a beautiful woman with blonde curly hair and warm eyes, all decked out in a red cowboy shirt and matching boots, ready to go.