Riding Barranca (4 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

Once in a while after dinner, if our father was in the mood, he would clap his hands together and ask if we'd like a story. In silent agreement we would huddle together on the dark red carpet and watch the fire as it transformed his kind, attractive face into something almost scary, grotesque. We didn't have to ask what he was going to read. It was always the same story: “Bluebeard.”

Our mother didn't stay to listen to Popi's favorite fairytale. She retreated to the kitchen to clean up the Formica-countered kitchen with its checkered floor, everything nice and orderly, the stay-a-bed stew put away in its Pyrex container, the budgie-bird tray swept clean. Our mother had a firm idea of what the perfect fifties family was supposed to be like and it included bedtimes, table manners, and nightly prayers.

“Open them all; go into each and every one of them,” our father read, “except that little closet which I forbid youâ¦.”

As the four of us children heeded this warning, delivered by our father's scariest voice, we would shudder in anticipation. I'd put a hand on Chipper's dignified head, hoping he would protect me. My other hand would slip through the opening in the mahogany coffee table, needing something to hang onto. Or I'd play with the empty, silver humidor, which retained the delicious scent of tobaccoâopen-shut, open-shut.

“She then took the little key, and opened it, trembling,” our father continued, excited by the terrible tension of the story. “At first she could not see anything plainly, but after some moments, she began to perceive that the floor was all covered with clotted blood, on which lay the bodies of several dead women, ranged against the walls.”

In the story the key fell from her hands into a pool of blood. We all knew that the stain would betray her. Bluebeard would know that she knew!

The waves above the fireplace should have sprung into life at that point in the story, crashing against the shore, washing the key with its magical waters. But my father read on in a tone of great warning, as if we too must always obey and never violate the sanctity of the closet.

Luckily, Bluebeard's wife had a younger sister, who ran to the top of the tower to look out for their brothers. LO! There in the distance came the rescuers ridingâtwo brothers racing across the desert, approaching in a cloud of dust! I liked this part of the storyâriders coming to the rescue. I wondered if my own two brothers would be as valiant.

In the story, the brothers arrived just in time, as Bluebeard took hold of the young wife's hair and prepared to strike off her head. Before he had a chance, the brothers sprang up the steps and ran their swords through the old man's body, and all four happy siblings were united.

After that cheery ending, it was time to kiss our parents goodnight, then trot upstairs, where we could say the Lord's Prayer and have “Sweet Dreams.” No wonder I had recurring nightmares.

Now Mom rests in the corner of our big French-blue sofa, propped up by pillows, sipping her

faux Bellini

âbubbly water

and pomegranate juiceâserved in an elegant champagne flute. I call her, “My Baby Mama,” and she smiles back, saying sweetly, “My two little girls.” Not so little, I think.

It is hard to imagine our mother dying. She has always had such a strong constitution and an almost manic energy. I could see her dwindling life going on and on, slowly rolling downhill into that murky region of Alzheimer's land, the mind giving up, but the body resisting.

Six years ago my relationship with her was so different. Even now, I am still finding my way back to the mother who'd rejected me out of misplaced jealousy and anger.

On the morning of my father's death, my mother called our house eight times telling me NOT to come to ScottsdaleâI was not wanted, my father was fine, I was not allowed in intensive care, he could not be disturbed, he was stable, no problem, he needed to rest, I would only be in the way.

My husband Mason thought that I should wait and respect my mother's wishes. But I had respected those wishes for the past several months, staying away, even though we were living only three hours south in the little town of Patagonia. When I wanted to visit my father in his failing state, I was told, “Why don't you wait until you're asked, Laura?”

But my older brother, George, sensed the pressure of time. “Dad might not make it through the weekend.” This shocked me. I didn't believe it, but I called the Mayo Clinic to check on my father's condition. “Is it true that he can't be disturbed?”

The nurse said, “He's expecting you.”

Luckily I had my cell phone and was able to get directions as I entered Phoenix. When I spotted the clinic across the barren field, it looked like an enormous jack-in-the-box, a monument to illness.

I dashed up to intensive care where a doctor greeted me at the security door, escorting me to a windowless anteroom. “About twenty minutes ago,” the kindly doctor began, very tentative, not knowing how I would take this, “your father seemed stable. We thought he was doing well.”

Just minutes before my arrival, Popi had been talking and joking with his doctors, and then suddenly something changed. Part of him had slipped away. I took this news in blankly.

The doctor led me to a nearby room where Popi was laid out on a table, tipped at a disconcerting angle, so that his head was lower than his feet. He was hooked up to various machines with flashing, changing numbers. Numerous doctors stood in a semicircle by his bedâone Indian doctor wore a turban and held a fist to his mouth. It was as if representatives of healing from all over the globe had flown in to be in attendance. They were silent, respectful, observing their patient.

I went down on my knees, taking his hand. “Dad,” I said, “I'm here. It's Laura.” His face looked so handsome, peaceful.

No response.

Mom was at home in bed. She had just received a phone call, telling her to come.

Later she told us that just moments before her phone rang, a bobcat slowly sauntered past her bedroom window, right next to the huge plate glass, peering in. I couldn't help but think that my father, the prankster, had chosen the body of a bobcat to tease her, to make his last farewell, all the while enjoying the fun of startling my mother out of bed.

But now it was as if I was talking by cell phone, not knowing if we were still connected. The circle of doctors slipped away. Only one remained. “What do those numbers mean?” I asked. They were steadily falling from 113, to 110, 98, 97â¦

“His heart is slowing down.”

“Shouldn't we try to keep him alive until my mother gets here?”

The doctor responded, “Just this morning, your father requested no heroic measures.”

I nodded.

Popi's hand was still warm, still alive, so I whispered the Lord's Prayer and told him how much we all loved him, how he had been the very best father, that we would take care of Mom and his horses. “Go, Dad, go. Don't hold on. It's okay. You know that we love you very, very much.”

And then just as easily as a fountain clicks off from its steadily rising and falling motion, the water of his life became still. Peacefully silent, without any pain or even a gasp, as simple as that, it was over. The numbers rested at zero.

Then my mother walked in. The first words out of her mouth were, “What are you doing here? I told you not to come!” followed by a weeping intake of breath, as she went to him, her husband.

As I left the room, Wanda, my parents' housekeeper for over twenty years, was backing away. “What are we going to do now?” She didn't know how she would function without his kindly protection.

She went on to tell me how close my parents had been during those final weeks. But he had been tending to her, and no one had been looking out for him, as he didn't like having anyone hovering over him. After all, he had spent most of his life trying to escape “The Mother,” and he had done a fine jobâhe had escaped us all, for good.

When I went back into the room a few minutes later, Mom was still whimpering. I sat down on the edge of the bed beside his body and said to her, “Our relationship is going to be different now.”

She answered simply, “Yes.”

And then, it was as if some dark tattered veil fell from her shoulders, the shroud she had worn for him, like a protective cloth that deflected attention away from his secret life. It was

an instant of transformation that I could barely trust, though the change itself was visceral. She no longer seemed to hate me. She had become like a child, needing me, wanting me to stay with her, but was the rivalry really over? Were we allies now in death?

Sitting together now in our living room, the fire settles down into embers, and my sister and I start getting silly, laughing over the blog I tried to create for this book last fall.

“The day I wrote my first entry, I was going down this flat dirt roadâthere were no holes or ruts or anythingâ and Rocket just fell down, on TOP of me!” We all find this hilarious. “And then the next day when I searched the Internet, I couldn't even find my own blog!”

At last we can laugh together.

Tonka's Eye

Riding Barranca beneath the big-boned sycamores that line Harshaw Creek, a few leaves left clattering, little golden balls dangle like leftover Christmas decorations. Picking our way

around thorny mesquite, I break branches where necessary, so that each time I come this way there will be less chance of getting clawed.

In Massachusetts, falling off is not such a threat. The earth is sodden, and the trails often soft with mud. But here in the desert the ground is like cement, the climate harsh, trees rough and ready to get you. Old mesquite breaks brittle in my hands. Riding out onto the sand of the wash feels safer, and I let Barranca canter. He has a lovely fast walk and a graceful, smooth lope, but he is still somewhat wary of cattle.

Climbing up an extremely rocky hillside, he keeps trying to turn toward home, but I insist, firmly, and he goes on. Not far away, there is a little turn out, and I see that many transients have come through here. There is a scattering of plastic bottles, black-washed for camouflage, discarded clothing, toilet paper stuck in crannies, a little cave with a sleeping ledge, opened tins of food, the remnants of a fire for cooking or warmth.

One border patrol friend, Danny Cantou, said, “You don't see them, but they see you.” Danny informed me that they recently captured five men with semiautomatics in a cave right above one of the gates I open to go toward the Hale homestead. Last year I found six, fifty-pound bales of marijuana less than a mile from our house, and more recently a truck with 1,850 pounds of grass was apprehended on our small road. In response, the border patrol began setting up sensors along various footpathsâone of which is a favorite riding trail.

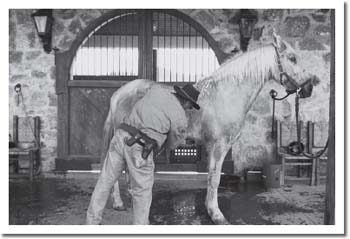

When I get home, I give Barranca a bath with warm hose water, then work some Cowboy Magic conditioner into his tail and proceed to comb out the snarls. I've heard that horses are quite proud of their tails, and his is exceptionally long and thick, almost sweeping the ground. The dark brown strands

are streaked with gold, just like his fetlocks. I think he likes the feel of his dust-free hide, the sensation of my hands separating the strands of his magnificent banner.

Washing Tonka

I decide to take Barranca out today, and put my friend, Phil Caputo, on Tonka. For the most part I am the only one who has ridden Barranca these past three years, and he has responded well to my consistency, but now, too often, I am tempted to let others ride him because he is the easiest horse with the best gaits. I know Tonka is a bit of a challenge, but Phil is a trooper.