Riding Barranca (3 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

Bringing the Horses In

This morning looks like it will warm up quickly, and I decide to trailer Barranca up to Flux Canyon. There are still remnants of snow here from the big storm ten days ago. We climb the hill from Mowry Road, and begin the descent on the other side of the ridge. My Standard Poodles, Bali and Cello, are with me today, padding along in tandem. There is nothing nicer than riding out on a good, steady horse with attentive dogs by your side.

Maybe this isn't snow, but a strange white powderâ calcium, gypsum, alum? There has been a lot of exploratory

mining going on in these hills recently. It seems tragic to disturb the peaceful grandeur of these mountains just to collect copper, silver, or manganese for fiscal gain. But today it is amazingly quiet. I feel like I am the only one enjoying this great expanse. Nobody else is out here,

just me and the drug runners.

Continuing on down the slope, I can see Mount Wrightson poking up in the distance behind Red Mountain's muscular yet feminine form. Up ahead there's a huge grey outcropping I like to think of as “Rhino Rock”âso different from the rest of the iron-rich, red-colored mountains. I wonder about this landscape, its geologic historyâwhat it is made of, when it was formed.

A deer bounds away up the slope, and I am aware that mountain lions are becoming more of a presence. Recently a friend saw three grown lions crossing Harshaw Creek Road just a hundred feet from our driveway. Surely there are enough deer around to satisfy these carnivores, but still it worries me. I imagine seeing a big cat, and wonder what I would do to scare it away. Would it be interested in my dogs, trotting along so faithfully?

I have forgotten my water bottle and am now very thirsty. Barranca stops to sample various puddlesâsome of which are probably filled with iron or sulphur or worse. Who knows what elements the mining has disturbed? The proposed Wildcat Mine is planning a massive 150-acre open pit with trucks running down Harshaw Road every eight minutes. I wonder how the Forest Service, which is supposedly the steward of our public land, can let this happen. Who knows what this operation will do to our already compromised water, not to mention the rest of the local ecology?

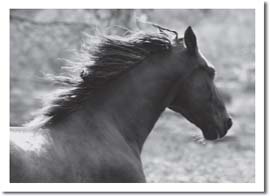

Barranca on the Move

My sister Cia arrives today with Mom and Wanda, our mother's caregiver. Mom's Alzheimer's has clearly progressed. After greeting me, she asks, “Whose house is this? Have I been here before?” though she has visited me three times since November. Her mind is like a Teflon panâeverything sliding right off. Mysteriously, this diseaseâso terrible in many waysâhas allowed her to forget many of the conflicts of our past and has made her a much nicer person.

The beds are all made, and supper composed, so I urge my sister to come out and ride with me. I am willing to give her my best boy, Barranca, though she is somewhat wary due to her last ride here a couple of years ago, when a friend's horse dumped her in the wash.

As we head out, I suggest that we try to focus on riding, and not talk too much, for I have noticed when riding with groups of womenâand surely I am as much to blame

as my companionsâthere is an almost compulsive need to communicate. Often a ride of three or four can be a cacophony, close to distracting.

It is nice to be comfortable enough with a riding partner (like I am with my cousin Helen) to not have to talk constantly. But Cia and I have a lot of catching up to do. We are both concerned about our motherâher medications, her bruising, her balance, and of course, her mental state.

We proceed up a very steep hill where Cia can get a full view of the mountains. It pleases me to hear her awed response to this expansive desert landscape.

La Roca

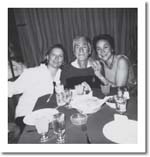

Cia would often visit me here in Arizona, bringing our ailing father down from Scottsdale. Since I was not welcome at my mother's house for the past few years, this was the easiest way for me to see them, and I always looked forward to their company.

On his last visit to Patagonia, we took Popi across the border to La Roca, in Nogales, Mexico. But did we push him too far, ordering chicken mole, letting him drink margaritas, forbidden in terms of his therapy? We hired mariachis to play

“Rancho Grande” and had our photo taken together, one adoring daughter on either side. At the time, we didn't realize that this would be our last meal together.

Popi's story is a big part of this narrative, for he played a major role in the conflict between my mother and me. I cannot really understand my mother or the dynamic between us, without looking at our family as a whole.

As children, we would wait for our father to come home, anticipating his return. Mom would dress up every night like a good fifties wife, meeting him at the door with a hug and a kiss. They would have cocktails, usually a glass of sherry in the library, and I would fiddle with the combination on his caramel-brown briefcase, 3-9-5, until it popped open, exposing his gargantuan legal files.

He was a big important man, not only to me, but to that other world of business. Yet I could see he often drifted in a daze. I was like him, both in temperament and looks, big-boned, hazel-eyed, with a naughty sense of humor. Popi liked to have a good time and his circle of friends embraced him. He liked to include anyone and everyone, while my mother wanted to keep everybody out. She wanted him all to herself.

On those nights when we ate together around the formal dining room table, it was a chance to teach us manners, but with milk spilling down the mahogany cracks, my jumping up and down, David's antics, Cia's diabetes, George's baiting, and Popi's amusement by it all, how could our mother maintain a civilized dinner? She often ended up in tears.

I didn't realize that what was bothering her was something more important than manners. I remember her sometimes sitting there in silence, barely picking at her food. Even if we asked her a question, she would not speak. One cannot say the unthinkable.

But when they went out in the evening, it was a different mood. Popi would be all dressed up in seal-like-sleekness, with flat pearl studs running up his crisp looking shirt. His gloves were immense and lined with real cashmere. His ring was a garnet signet ring. The emblem on that impressed me. Now I wonderâ where did that ring go? Did he give it to one of his “friends”? And how glamorous she looked on the way to the opera or symphony, her hair done to perfection, her jewelry and dress so elegant. She would walk away on his arm with such grace.

But I felt a pang of abandonment when they left me at home with my siblings, all of us together in the breakfast nook, inspecting eggs for that dreaded clot of blood, or eating creamed tuna fish in fried potato baskets as our elegant parents slid past us, wishing us all a most fragrant goodnight.

I liked the roughness of my father's cheek on the weekends, his long yellow legal pads, and his peculiar print-script, the cardboard embedded in his freshly cleaned shirtsâwhich I collected for my writing and artworkâhis impressive china dog collection, which I emulated with my own assortment of horses. He had a compulsion to see things clean and neatâSaturday morning room inspection, mad polisher of shoes. He would lead wild dashes in the airport, hollering for attention, “Run! RUN!!!” Just-making-it-without-one-minute-to-spare was his favored method for takeoff. To him, creating anxiety was part of the program, though he thought it all a big joke.

I can't quite picture our mother running in her narrow skirt and two-toned heels. Once Popi got to the gate, huffing and puffing, perhaps he managed to convince the stewardess to hold the plane until our mother sauntered up, southern style. I think he really liked her complaints, which he pretended not to hear, making her even madder. He liked playing the part of “bad boy,” doing exactly as he wanted, riling her up.

It was only after a hard week's work that he finally seemed utterly spent. Then he was ready to get down on the dark red carpet and let me ride his back, bouncing before the fire, giving me a good buck.

Ready to Load

Cynthia Carlisi is coming over to give Mom a massage today, but my horse trailer blocks Cynthia's arrival, and Barranca is balking again, not wanting to load. I'm getting really tired of this. Cynthia gives her free adviceâ

Don't use food or treats to entice a horse into a trailer.

I agree, but often opt for the easier way outâa handful of grain or a carrot, though neither is helping today.

Barranca keeps veering off to the side, and I try backing him up, as Les Spath did when he came to train Barranca in Massachusetts. Les took his time and was clearly the boss. If Barranca wouldn't load, he had to back up. Most horses soon learn that it is easier to go forward.

But now there is way too much nervous energy all around and perhaps Barranca is picking up on that. Finally, with Cynthia clucking from behind, Barranca makes his move and loads. I close the divider and Tonka hops in, then Cia and I drive up the washboard-rough road and disembark in front of the Hale Ranch, with its graceful meadow slopes. It reminds me of some turn-of-the-century homestead with its old wood-and-tin outbuildings and mesquite stick corral.

After warming the horses up, I suggest that we canter to the top of an incline. I go first, loping gently, but I hear a rustle in the bushes behind me and then a

yelp

from my sister. Barranca has shied, unusual for him. I can see that she has lost her stirrup and is unbalanced, but at least she stays in the saddle. “Did something spook him?” She doesn't know, but I don't want to see my sister take another fall, so I suggest that we take it easy.

Tonka feels like quite a handful today. He keeps throwing his head up and down, acting competitiveâhe hates to have Barranca ahead of him, especially when we canter. Barranca, always the equine gentleman, allows the unruly Tonka to go before him. Sometimes when Tonka acts out like this, I am reminded of a misbehaving child, and how that reflects poorly on the parents. Most likely I only have myself to blame for Tonka's faults.

That night we set up a fire in the living room and turn the lights low. Our mother is in an excellent moodâso happy to be visiting, to be here with us both. The glowing hearth makes her feel at home, for she always had a passion for building a fire.

Every night before dinner Mom would crush newspaper and stuff it beneath the logs in the living room. The fire flared up beneath

a painted sea scene that hung above the mantel where waves were caught in an eternal crashâfar from our Midwestern landscape.

On occasion, we would set up those flimsy TV-dinner trays and watch the fire for entertainment. My older brother, George, and I would take turns throwing a special chemical powder onto the blaze, creating tongues of blue and green, while Cia and David, sprawled on the floor in their footsie pajamas. Chipper, our Boxer, lay asleep on the floor. I rubbed his floppy ears.