Riding Barranca (8 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

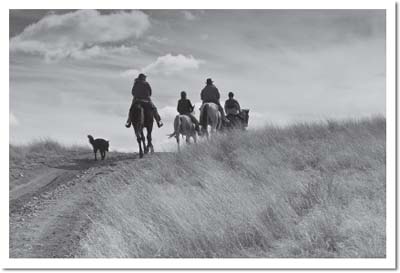

But first we feast on the best breakfast in town and have cup after cup of strong coffee. Then Erma heads off to the notary to get the title to her little “ruin,” which she purchased three years ago. She will join us for dinner out in Aduana, a small village about fifteen minutes away. Leon, a Mexican cowboy, is waiting for us there with three horses tied to a

chalate

tree, an enormous fig.

Again, I use my own saddle, and Leon admires it, though I have to redo his cinching. I think this annoys him, but I don't want to ride with a large knot of leather under my knee. Leon does not speak English, and despite my blank stare, he assumes I can understand his instructions. I gather that he wants me to keep the horse's head up high as he thinks the horse might trip otherwise, but many Mexican bits are so tough I want to handle her mouth gently.

Teri is all decked out in Argentinean gearâa maroon poncho trimmed in black and a flat-topped gaucho hat. “I might not know how to ride,” she laughs, “but at least I look good!”

Leon's nephew is accompanying the ride on foot. They feel they need an extra man along in case anyone gets into trouble. I wonder what kind of trouble they are imagining, but no one thinks that last night's rain will cause a problem. In fact, the earth looks dry. One of the largest fig trees in the area grows near the wash, perched on top of a wall with its rope-like roots streaming down the embankment in a combed out, mud-grey flow.

Quickly climbing up out of Aduana, we comment on the petrified mining sludge that has been left like frozen lava on the hillside. Passing the luxurious home of two renovators, Peter and Bob, we note a flame tree blazing with blossoms in their well-kept courtyard. The long main building was once part of the mining operation, as the mine had to bring silver over the mountain by aerial tram.

There are some stray cattle along the way, accompanied by the sonorous sound of cowbells. The horses know the trail and seem sure-footed.

Pochote

trees (also known as kapok) are scattered here and there. The large seed pods have opened to expose little puffs of white fiber. Sometimes the birds line their nests with this cozy cotton, but the local Indians also gather the fiber, spin it, and use it in their weaving. Long-tailed blue-black magpie jays take off into the mountain airâ

exotico.

Squeezing through one narrow rickety gate, we each take turns ducking under a low-hung tree and scramble up some loose rock to get to the trail. Then it is fairly easy riding. All my fears are blown away. There are no radical drop-offs, only tremendous views.

As we continue climbing,

Casharamba

is dominant in the distance. This flat-topped mountain reminds me of one of Yosemite's majestic peaks. Not surprising that the local Indians consider it a holy mountain. Its name means “needle in the ear” because there is a hole in the base of the rock, like a pierced lobe. I wonder if the wind whistles through there at times, speaking an unknown language to the indigenous.

At the crest, we can see all the way to the Sea of Cortez, and in the other directionâthe Sierra Madre and the beginning of the

Barranca del Cobre,

Copper Canyon.

We are headed for the ruins of an old mine that was once owned by the mayor of Alamos. He reasoned that Sonora could use a prison and that the prisoners could help work his operation. This was a prison without bars, because apparently no one had the energy to escape after a long day's work. In fact, the life expectancy of the prisoners after incarceration averaged only eighteen months.

We begin to descend and look out over uninhabited land. It is already getting warm, and we all strip down to our t-shirts, tying extra wraps to the backs of our saddles. After an hour or so, we come upon the abandoned mine buildings, with one towering smokestack made out of well-maintained brick, but the stone foundation of the old hacienda is crumbling. We tie up near another massive fig tree that reminds me of Peter Pan's hideout.

Wandering about the ruins, we come upon a brick tunnel. Walking inside, I smell bat guano and see a mass of tiny bats flying aboutâdisarming. We are told that the prisoners had to enter this tunnel at night, first on their knees and then flat out on their bellies before reaching the sleeping quarters where twenty to thirty men were housed.

Settling down at the base of a fig tree, we share our snacks, though we want to save our appetites for Sam's in Aduana, knowing we'll have a feast of

boltanos,

platters of family-style food. Teri pulls out her cell phone andâguess whatâ“No

reception!”

Leaning back against the trunk of the tree, we talk about the ride that Teri is going to take with some women-friends in Africa. “I might not be the best rider, but at least I know how to have fun,” she laughs.

After an hour's rest, we mount back up and retrace our steps. It is always interesting to experience the landscape in both directions. We can now see the little village down below

and the town of Alamos to the west. It is about a nine-mile ride, and as we come into town, we feel triumphant. Cantering up the last stretch of cobblestones toward the church plaza, a herd of goats dances around us. One little guy even bounces up onto the stone wall to get out of our way.

It is only four o'clock and we have an hour before the others arrive for dinner, so Rosemary and I have a cup of tea before we head over to the cooperative shop up the hill. Here local women make all sorts of primitive dollsâthe more naïf the better. There are tiny purses fashioned from goats' balls, trimmed in gold with dangling fringe. It is a most curious assortment of finds: tiny, old burro shoes, minerals, hand-stitched pillows, and rustic baskets made from saguaro cactus.

An elderly man takes us into his house at the end of the lane. He has an old carpenter's chest for sale, painted orange and blueâit would make a perfect tack box. When he opens it up, I see that the chest contains all sorts of treasures: a bag of old coins, baby shoes, his passport and other important papers. It seems sad for him to part with it, but he assures me that he wants to sell.

Soon Erma and the others arrive. Sam serves up some excellent margaritas, and we are all ready for the

boltanos

that followâgrilled shrimp, marinated in an orange marmalade mixed with five kinds of chilies, garlic, oil, vinegar, and sugar, delicious, especially because they've been grilled in the shell. We peel and devour them by hand. Then a delectable chipotle-creamed chicken with slices of apple, and another platter of filet mignon and local green beans. Finally, there is chocolate cake and coffee to get us back on the road to town so that we can get to the evening performance. Horses and opera, feasting and fete-ing, all on the night of the full moon.

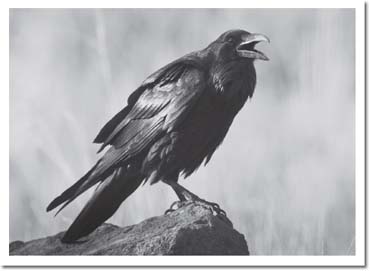

Raven

Two ravens have made themselves at home in the horse paddock. I assume they have come to gather dropped bits of grain. They sit together on the gate like a pair of old cronies contemplating their domain. I wonder what the horses think of them. Do they consider them part of the herd, part of our extended family?

Wind

Not in a great mood even on waking. Why. Is it the wind? I hate the wind as much as the horses do. I even prefer a blizzard or hail to this incessant blowing. They say that the wind carries the scent of predators and that is why horses get spooky.

Helen arrives with her trailer, and then Phil and Leslie show up, but taking all three of my horses out is a lot of work with the machinations of feeding, mucking, catching, grooming, saddling, bridling, and loading. Tonka steps on Phil's foot. Then driving out of the paddock, I ram the side of the trailer into a fence post, bending a fender up against the tire. We have to get out a hammer to pry the metal away from the rubber or we'll have a flat in no time.

Wind.

Heading Out

Helen remains calm and patient, even though riding with four people on a day like this seems crazy. Up on the San Rafael the wind is even more intense and the horses are unnerved. Everything seems an extra effort. Phil has trouble with his saddle, slipping, his stirrups too long, uneven, and then he pulls so hard on Peanut's mouth, I have to insist that he ease up. Wind,

wind,

WIND!

Under the Sycamore

Heading to the barn to grain and ready the horses, I groom out all the mud that has accumulated on their coatsâlittle pigpen boys. Barranca gets into the trailer with ease, and then I load Peanut. He doesn't realize that after this morning ride with Leslie, we will be taking him over to Melinda South's for training while I'm in Australia for two weeks.

Mason and I rented a house at the end of Blue Haven Road when we were building our place. I often took long walks with the author Jim Harrison there. He and his wife, Linda, were our closest neighbors. I made their acquaintance by hanging a little bag of New Year's gifts on their gateâa pear, a firecracker, and a note asking if it was okay to harvest watercress from the Sonoita Creek that ran by their house. He wrote back immediately, saying,

“NO!” I should not eat the watercress or I might get giardia.

That was the beginning of a good, long friendship, which we have had over these past ten years.

Leslie and I decide to ride all the way to the Harrison's house this morning, passing the Nature Conservancy and then the Circle Z land where I used to ride when I stayed at the ranch with my sons. We cross the creek at the end of the road. The water is deep here, and the horses take a long drink. The Harrison's gate is open so we ride up to the house calling out,

“Yoo-hoo, anybody home?”

Both Linda and Jim come out to look at the horses. I tell them that we've come for an espresso, and they invite us in. “Just kidding. We've had enough caffeine for one day.” Besides, we've got to get back to Melinda's. We're running late.

When we arrive, Melinda's gate is wide open, and her two horses are wandering about the lot freely. Peanut seems a bit nervous eyeing the unfamiliar yard and animals, including a small brown calf named “Steak.” We shut Peanut into a pen, get him some hay, and unload grain. I hand over his bridle and attempt to leave a bag of carrots and apples, which could be given to him with his morning feed, but Melinda says that she doesn't like to feed apples because of the carbohydrates. I've never heard that one before. But this is her place, and she is the trainer, so she can call the shots.