She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (4 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

South Africa, 1932â1960

THE OFFICIAL REASON

my mother gave for leaving was politics. “I couldn't stand the politics,” she said, and pointed to March 1960, when sixty-nine people had been killed in Sharpeville while protesting against apartheid. She had been to a couple of meetings, she said, and had to decide whether to stay and commit or leave altogether. This was the story as she told it.

No one in her family had ever been to England. Her father's ancestry was Dutch. Her mother's, she said, had been French. But like most English-speaking white people in the former colony, she had grown up thinking of England as a point of origin. She was a great reader and had plowed her way through the nineteenth-century English novels. She identified strongly with Jane Eyre, even more so with Bertha Mason, and not at all with Cathy, in

Wuthering Heights

, who she thought made a spectacle of herself, carrying on like that at the window. She would have sympathized with Virginia Woolf's put-down of Katherine Mansfield, who was said to have appeared in ghost form after her death, which Woolf thought typical of the woman: to be caught leading such a “cheap posthumous life.” Her favorite Austen heroine was Elizabeth Bennet, for what she saw as her keen lack of hysteria.

I knew she had been born in Durban, in her auntie Kathy's house, and that when she was two years old her mother had died of tuberculosis. I also knew that around the age of five her father had remarried. But of his second wifeâwhere they met, who her family was, or anything much about her beyond her name, MarjorieâI knew nothing. My mother had no sympathy for her, although her life would seem to have been hard. She was pregnant for more or less a decade after marrying my grandfather, and my mother, like many eldest children in a family that size, was put in the position of surrogate parent to some of her half-siblings.

She never called them “half.” She called them “my brothers and sisters.”

If it struck me as odd that we never saw or heard from them, I didn't dwell on it. Like most children, the life my parents led before I was born was a rumor I didn't believe in. When I gave her childhood any thought at all, I thought it sounded kind of fun; like

Cider with Rosie

, but with deadlier wildlife.

My mother was tall, slim, not athletic exactly but aware of her own strength. She was very blond as a child, and no matter what she did with her hair, couldn't get it to curl. This was the era of Shirley Temple, and my mother presented it to me as the tragedy of her childhood: lank hair. But she had large brown eyes and high cheekbones, and one day, as she left the schoolyard, two little boys shouted after her, “We love you, we love you!”

Math was her subject. She worked hard at school, each week competing for first place with a girl called Stella, but whereas Stella was gifted, said my mother, she had to work for it. She gave me a meaningful look. “Oh, cut it out,” I thought. She wanted to be a nurse, but the teacher took her aside and said, nonsense, you should be a doctor. Since most of her schooling took place in English-speaking Natal, in the southeast of the country, she never learned Afrikaansâwhich didn't stop her, years later, startling Dutch guests around the pool in Majorca by trying to use it to engage them in small talk, while I slid behind my paperback and pretended to be Spanish.

“We love you, we love you!” Eight-year-old mum with her brother, Michael.

She sometimes referred to her father as Jimmy. He had worked in the gold mines or as an engine driver, and she was rather proud of the latter; of the two jobs, it's the one she chose to list as his profession on her marriage certificate. She showed me a poem he had written once, which he had given to her when she left South Africa. It was called “Salutation to the Dawn” and was full of soppy descriptions of the sky and wildlife. “He probably copied it out of a book,” she said bitterly, a rare break in tone. Most of her recollections ran along jollier lines.

She told me her brother knew Tarzan, and I believed her. (My dad tried to rival this claim by saying his brother knew Kermit the Frog, but this I did not believe. His brother lived forty miles away in London and Kermit, as everyone knew, lived in New York, with Miss Piggy.)

She told me of various capers involving the family dogs. One was killed at a picnic when a scorpion bit him on the nose. Another, Caesar, was killed when a neighbor threw out a piece of steak for him, studded with glass. My mother couldn't remember why. At one point they had a Great Dane that adopted a baby chick from the yard when its mother abandoned it. They called the chick Tarzan and let it sleep in the crook of the dog's giant forelegs. When they put food out for the dog, Tarzan would hop onto the side of the bowl and eat with him.

“What happened to Tarzan?” I said. My mother looked blank.

“I can't remember. We probably ate him.”

It didn't occur to me until much later that the moral of most of my mother's stories was “look lively or die.”

She told me about Flora the maid. They were poor, said my mother, but they were still white and so, despite having nothing, a succession of black women roaming the countryside with even less installed themselves in the kitchen and started work in the hope of eventual remuneration. “Poor things,” said my mother. She remembered Flora in particular. She had been abandoned by her husband and had gone around the bend. Every day, she dragged the gramophone out into the yard and wedged it beneath the peach tree, which she climbed to scan the horizon for her lost love, while Tony, my mother's little brother, stood sentry at the base of the tree. “Tony, where's my husband?” Flora wailed. “Tony, where's my huuuuuusband?!”âit was a great catchphrase of my youthâwhile the gramophone played “If I had wings like an angel / over these prison walls I would fly.”

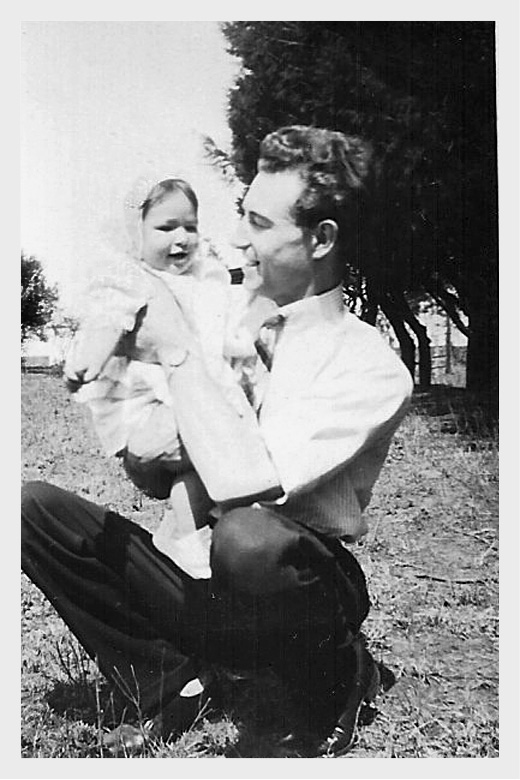

Mum as a baby with her father, Jimmy.

There was a single story my mother told from the period between her mother dying and her father remarrying. It wasn't even a story, just an image. They were living out in the wilderness somewhere, her father working night shifts in the mine, and he would leave her at dusk with an oil lamp burning. She was five years old. At some point in the night the lamp would burn out. “And I would be alone, in the dark.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

SHE DIDN'T BECOME

a doctor. She left school at sixteen and got an entry-level job as a clerk in an office. She had never been to the city before, and the night before her first day, she asked her father, who'd grown up in Johannesburg, if he would accompany her the next morning. He said he wouldn't and instead drew her a map of how to get from the bus station to her office. She spent her first lunch hour riding up and down the escalators in a department store. She had never seen anything so amazing in her life, she said.

When she was seventeen, her stepmother had another baby, a boy called Steven who was premature and cried and cried, said my mother; she remembered rocking him for hours and watching the soft, unformed top of his skull move in and out as he wailed. “Fay was my baby, Steve was my baby.” She sang to Steve endlessly, which is why, she said, he could never hold a tune later on in life.

In her early twenties she moved into a flat-share in the city with a girl she'd met at work called Joan. They went out on the town; my mother took to painting a beauty spot on her face, until she got caught in a rainstorm going to visit her family one day and it streaked. Her brothers fell about laughing: “Is that beauty spot washable?”

She changed jobs. She studied for an office-management certificate. For a while she worked at Unterhalter's Mattress Works (“Enjoy your repose with Rosey-Doze”). Eventually she got a job as a bookkeeper at one of the country's biggest law firms, where she encountered someone whose name would ring down through my childhood. Sima Sosnovik could have been a heroine from Tolstoy. She worked from a glass office overlooking the bookkeeping pool, whence she plucked my mother and groomed her for stardom. It is the only time I heard my mother give credit for her life to anyone else, except in the most general sense to the “good genes” she inherited from her mother's side. “She saw something in me,” said my mother. “She saw something in me and she saved me.”

Her first line to my mother, repeated down the years as if from a classic movie, and to be imagined in a Russian accent, was “You do your work as if you expect it to be checked.” My mother was mortified. It lit a personality trait in her that would last the rest of her life. There was never a penny unaccounted for in her transactions. Her checkbook was fanatically balanced. She kept records of everything: how long the water filter had been in the jug; how many times the semiperishable plastic bowl had been used in the washing machine. In her address book, she kept a record of every birth, death, divorce, and remarriage in the family she never saw or spoke to. She would look up, suddenly, from the sink and say, “It's my brother John's birthday today.”

“I have an elephantine memory,” she sighed. The curse of brilliance.

Sosnovik was the head of accounts, a title that, said my mother, if she hadn't moved to London would surely have been hers one day. I have a photo of this woman, posing on the deck of a ship sometime in the 1930s. She is elegant in a pencil skirt, with wavy red hair, holding a cigarette. She looks like Norma Shearer. Sima Sosnovik.

“What happened to her?” I said once. It was dangerous to veer off the chosen path of my mother's story, and her face clouded instantly. “She died,” she said. End of discussion.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

IT WASN'T LONG AFTER

this that my mother saw the ad in the newspaper, a “once in a lifetime” special offer: a one-way passage to England, a week in a hostel in Earl's Court, and tickets to a West End show, for £5 all in. She took it as a sign, resigned from her job, sold all her furniture, and sailed that November. After a two-week voyage the ship docked at Southampton, where a telegram was waiting for her at the Union Castle office. It was from her stepmother, who, after filling her in on her siblings' goings-on over the past fortnight, informed her that while she was at sea, her father had dropped dead of a brain hemorrhage. He had been buried when she was somewhere around the Azores. All she would say of that first winter in London was that it was very cold and she found the people peculiar.

Like a heroine from a movie, Sima Sosnovik, my mother's mentor and friend.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THAT WAS THE STORY

as my mother told it. Since then, she had seen her family a handful of times. Fay, her sister, had come to stay before I was born, with her then-husband Frank. There was a photo of them festooned with pigeons in Trafalgar Square, Fay wearing Nana Mouskouriâstyle glasses, my mother grinning, and even Frank looking quite jolly. He had disgraced himself on that trip, said my mother, by refusing to travel on the Underground and demanding his dinner at the same time every night. My mother did an impression of him: “Faith, where are my boiled eggs?” Frank was English, of course.