Shrinks (28 page)

Authors: Jeffrey A. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology / Mental Health, #Psychology / History, #Medical / Neuroscience

In the mid-1960s, biological psychiatrists began searching for a biomarker by comparing the urine of mentally ill patients and healthy individuals with a new technique called chromatography. Chromatography uses a special chemical-sensitive paper that turns a different color for each distinct compound it comes into contact with. If you place a drop of urine from a healthy person onto one strip of paper and a drop of urine from an ill person onto another and then compare the colors on each strip, you can identify differences in the types and amounts of the urine’s chemical constituents—and these differences might reflect the biochemical by-products of the illness.

In 1968, the biological psychiatrists’ chromatographic efforts paid off with a sensational breakthrough. Researchers at the University of California at San Francisco discovered that the urine of schizophrenia patients produced a color that did not appear in the urine of healthy individuals—a “mauve spot.” Enthusiasm among biological psychiatrists only increased when another group of researchers discovered in the urine of schizophrenics the existence of a separate “pink spot.” Many believed that psychiatry was on the verge of a new era, when psychiatrists could discern the entire rainbow of mental illnesses merely by instructing patients to pee on a scrap of paper.

Unfortunately, this urine-fueled optimism was short-lived. When other scientists attempted to replicate these wondrous findings, they uncovered a rather mundane explanation for the mauve and pink spots. It seemed that the putative biomarkers were not by-products of the schizophrenia itself, but by-products of antipsychotic drugs and caffeine. The schizophrenic patients who participated in the chromatography studies were (quite sensibly) being treated with antipsychotic medications and—since there was not much else to do in a mental ward—they tended to drink a lot of coffee and tea. In other words, the urine tests detected schizophrenia by identifying individuals taking schizophrenia drugs and consuming caffeinated beverages.

While the search for biomarkers in the 1960s and ’70s ultimately failed to produce anything useful, at least it was driven by hypotheses that posited physiological dysfunction as the source of mental illness, rather than sexual conflicts or “refrigerator mothers.” Eventually biological psychiatrists broadened their search for the diagnostic Holy Grail beyond the bodily fluids. They turned instead to the substance of the brain itself. But since the organ was encased within impenetrable bone and sheathed in layers of membranes, and couldn’t be studied without risking damage, how could they hope to peer into the mystifying dynamics of the living brain?

Throwing Open the Doorways to the Mind

Since so little was learned about mental illness from the visual inspection of cadaver brains in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, psychiatrists suspected that any neural signatures associated with mental disorders must be much more subtle than the readily identifiable abnormalities resulting from strokes, age-related dementias, tumors, and traumatic brain injuries. What was needed was some way to peer inside the head to see the brain’s structure, composition, and function.

The invention of X-rays by Wilhelm Roentgen in 1895 seemed, at first, the longed-for technological breakthrough. X-rays aided the diagnosis of cancer, pneumonia, and broken bones… but when early radiographs were taken of the head, all they showed was the vague outline of the skull and brain. Roentgen’s rays could detect skull fractures, penetrating brain injuries, or large brain tumors, but not much else of use to biologically minded psychiatrists.

If psychiatrists were to have any hope of detecting physical evidence of mental illness in the living brain, they would need an imaging technology that revealed the fine architecture of the brain in discernible detail or, even better, somehow disclosed the actual activity of the brain. In the 1960s, this seemed an impossible dream. When the breakthrough finally came, the funding that enabled it came from a most surprising source: the Beatles.

In the early 1970s, the EMI corporation was primarily a record company, but they did have a small electronics division, as reflected in their unabbreviated name: Electric and Musical Industries. EMI’s music division was raking in enormous profits from the phenomenal success of the Beatles, the world’s most popular band. Flush with cash, EMI decided to take a chance on a highly risky and expensive project in its electronics division. The EMI engineers were trying to combine X-rays from multiple angles in order to produce three-dimensional images of objects. Surmounting technical obstacles using profits from “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “With a Little Help from My Friends,” EMI engineers created a radiographic technology that obtained images of the body that were far more comprehensive and detailed than anything in medical imaging. Even better, the resulting procedure was not invasive and elicited no physical discomfort in the patients. EMI’s new technology became known as

computed axial tomography

—more commonly referred to as the CAT scan.

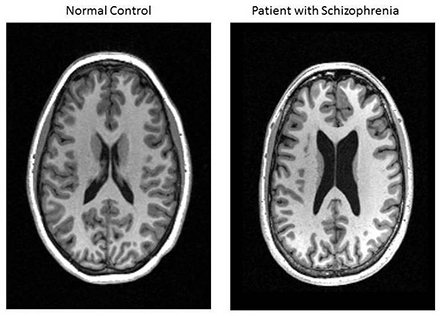

The first study of mental illness using the CAT scan was published in 1976 by Eve Johnstone, a British psychiatrist, and it contained an astounding finding: the very first physical abnormality in the brain associated with one of the three flagship mental illnesses. Johnstone found that the brains of schizophrenic patients had enlarged lateral ventricles, a pair of chambers deep within the brain that contain the cerebrospinal fluid that nourishes and cleanses the brain. Psychiatrists were thunderstruck. Ventricular enlargement was already known to occur in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s when the brain structures surrounding the ventricles began to atrophy, so psychiatrists naturally inferred that the ventricular enlargement in schizophrenic brains was due to atrophy from some unknown process. This landmark finding was promptly replicated by an American psychiatrist, Daniel Weinberger at the NIMH.

Before the shock waves from the first psychiatric CAT scans had begun to subside, another brain-imaging marvel arrived that was even better suited for studying mental disorders: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI used a revolutionary new technology that enveloped a person within a powerful magnet and measured the radio waves emitted by organic molecules of the body when they were excited by the magnetic field. MRI was used to image the brain for the first time in 1981. Whereas the CAT scan enabled psychiatric researchers to peek through a keyhole at brain abnormalities, MRI thrust the door wide open. MRI technology was able to produce vivid three-dimensional images of the brain in unprecedented clarity. The MRI could even be adjusted to show different types of tissue, including gray matter, white matter, and cerebral fluid; it could identify fat and water content; and it could even measure the flow of blood within the brain. Best of all, MRI was completely harmless—unlike CAT scans, which used ionizing radiation that could accumulate over time and potentially pose a health risk.

MRI in the axial view (looking down through the top of the head) of a patient with schizophrenia on reader’s right and a healthy volunteer on the left. The lateral ventricles are the dark butterfly-shaped structure in the middle of the brain. (Courtesy of Dr. Daniel R. Weinberger, MD, National Institute of Mental Health)

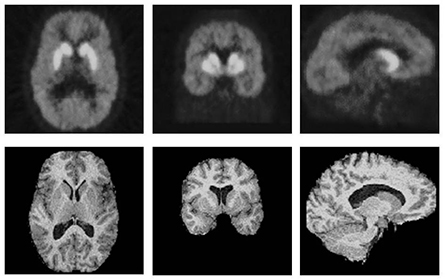

By the end of the 1980s, the MRI had replaced CAT scans as the primary instrument of psychiatric research. Other applications of MRI technology were also developed in the ’80s, including magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS, measuring the chemical composition of brain tissue), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI, measuring brain activity rather than brain structure), and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI, measuring the long tracts that carry signals between neurons).

The brain imaging bonanza of the ’80s wasn’t limited to magnetic technologies. The decade also witnessed the refinement of positron emission tomography (PET), a technology that can measure the brain’s chemistry and metabolism. While PET provides only a hazy picture of brain

structure

—compared to the fine spatial resolution afforded by MRI—PET measures the brain’s chemical and metabolic

activity

in quantitative detail. Perhaps anticipating the use of PET scans by psychiatrists, James Robertson, the engineer who carried out the very first PET scans at the Brookhaven National Laboratory, nicknamed the PET scanner the “head-shrinker.”

Diffusion Tensor Image of the brain presented in the sagittal plane (looking sideways at the head with the front on the right side of picture and the back on the left side). The white matter fibers that connect neurons in the brain into circuits are depicted removed from the matrix of gray matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood vessels. (Shenton et al./

Brain Imaging and Behavior

, 2012; vol. 6, issue 2; image by Inga Koerte and Marc Muehlmann)

PET scan images (top row) and MRI images (bottom row) of patients presented in three planes of view. Left column is the axial plane (looking at brain through the top of the head), middle column is the coronal plane (looking at brain through the face), and the right column is the sagittal plane (looking at brain through the side of the head). The PET scan is of a radiotracer (biologic dye) that binds to dopamine receptors in the brain which are concentrated in the bright structures (basal ganglia) in the brain’s interior and more diffusely in the surrounding cerebral cortex. The MRI that shows the brain’s structure, highlighting the gray and white matter and the ventricles and sub-arachnoid space containing cerebrospinal fluid (black), is used in combination with PET scans to determine the anatomic locations where the radiotracer has bound. (Abi-Dargham A. et al./

Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

, 2000; 20:225–43. Reproduced with permission.)

As a result of these magnificent new imaging technologies, by the end of the twentieth century psychiatrists could finally examine the brain of a living person in all its exquisite splendor: They could view brain structures to a spatial resolution of less than a millimeter, trace brain activity to a temporal resolution of less than a millisecond, and even identify the chemical composition of brain structures—all without any danger or discomfort to the patient.

The venerable dream of biological psychiatry is starting to be fulfilled: after studying hundreds of thousands of people with virtually every mental disorder in the

DSM

, researchers have begun identifying a variety of brain abnormalities associated with mental illness. In the brains of schizophrenic patients, structural MRI studies have revealed that the hippocampus is smaller than in healthy brains; functional MRI studies have shown decreased metabolism in frontal cortex circuits during problem-solving tasks; and MRI studies have found increased levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate in the hippocampus and frontal cortex. In addition, PET studies have shown that a neural circuit involved in focusing attention (the mesolimbic pathway) releases excessive amounts of dopamine in schizophrenic brains, distorting the patients’ perceptions of their environments. We’ve also learned that schizophrenic brains exhibit a progressive decline in the amount of gray matter in their cerebral cortex over the course of the illness, reflecting a reduction in the number of neural synapses. (Gray matter is brain tissue that contains the bodies of neurons and their synapses. White matter, on the other hand, consists of the axons, or wires, which connect neurons to one another.) In other words, if schizophrenics are not treated, their brains get smaller and smaller.