Six Miles to Charleston (16 page)

Read Six Miles to Charleston Online

Authors: Bruce Orr

A plat of land in Prince William Parish near Coosawhatchee River was surveyed December 13, 1770. It lists Nathaniel Heyward and George Fisher together as owners. These are obviously related, predecessors of the other Nathaniel Heyward (owner of Six Mile) and Colonel George Fisher. The fact that they were neighbors also means they were more than likely related as property was usually divided up and willed to multiple family members.

Nathaniel Heyward had another son, other than William, named Nathaniel Heyward Jr. He died in 1819, the year before William Heyward was executed. This is the very year of the sale in which Nathaniel Heyward received the disputed land and his heirs were eliminated. One was eliminated by death and the second was incarcerated and eventually executed.

The petition against William Heyward was in the amount of $7480.00, a pretty hefty debt. A portion of that belonged to the late James Fisher. It is a debt that would have fallen on his only male heir, John. It is also a debt that Colonel George Fisher would be interested in. If he could seize an asset of William Heyward, he would have a legal foothold in securing Heyward's debt to his deceased brother.

Could the reason John Fisher was inhabiting the Six Mile House be because William Heyward had given it to him to repay the debt he owed John's father? After all, John was a living heir and entitled to repayment of the debt before his uncle, the executor, was.

Colonel George Fisher was involved in disputes with the U.S. government over land that he had prior to the Indian wars. His land was invaded in 1812 and 1813, and he had to flee. The government had moved into North Carolina to quell the Indians and restore order. He was not only trying to collect on his deceased brother's affairs in South Carolina, but he was also dealing with his own in his home state of North Carolina.

Colonel Fisher had a daughter named Anne Amelia. In 1817, she married Jack Ferrill Ross. In 1819, Jack Ferrill Ross was the first territorial state treasurer for Alabama. His wife was pregnant and would give birth to William Henrys Ross in December. Now remember the lynch mob and the first assault victim, David Ross? It is all beginning to tie in and come together now.

We now have evidence of a land and property dispute not only among various heirs of John Wragg, but also James and George Fisher, the government and the heirs. The evidence shows that William Heyward was rightfully on his father's property. With the Five Mile House and Six Mile House both belonging to Nathaniel Hayward as of 1819, the Fishers were also legitimately there. The Lynch Law seizure of the land by the mob was a pretext as most probably was the assaults on both Ross and Peoples. We now have reason and motive for the attack on Five Mile House and Six Mile House on February 18, 1819. Nathaniel Hayward had just appropriated the landâa land valuable for potential use to the military and land desired by both Colonel George Fisher and Governor Geddes. One now understands that if the Fishers had been condemned and executed for the assault on David Ross that would have given Colonel George Fisher a foothold on the land. By switching to the John Peoples case, this eliminated that foothold giving Governor Geddes and Charleston a chance at the disputed property.

It appears, from the evidence gathered, that the Fishers and Heyward were innocent in regard to where they needed to be and also in defending their property. It is strange how out of the twelve arrested for such a horrendous crime that only the owners of the properties were executed. Nine others walked away from the hangman's noose, a lot different than the legend. Remember the Toohey brothers? One was executed for murder and one received a branding in regard to the same incident. This shows that the judges in Charleston had discretion in sentencing. Peoples was beaten and robbed of between thirty five and forty dollars, and three people were executed. The Toohey brothers murdered someone, and one of them went free. The point is the charges were deliberately changed so that the three proprietors could be executed and eliminated.

Up until now there has been nothing known in regard to the lineage of either John or Lavinia Fisher. It is now known that Colonel George Fisher of North Carolina was John Fisher's uncle. This is the first connection made for him. But what is known about the lineage of Lavinia?

Lavinia has always been a dead end as far as genealogy. No one has found anything regarding who she was, who her parents were or where she came from. All anyone knew was that she was born in 1792 by simple mathematics. If she died in 1820 and was 28, then we know her date of birth. We also know that she was different than most of the fair-skinned women of Charleston. One source described her as an “Amazon or a Termagant,” meaning her skin was darker.

We also know that Lavinia believed in her innocence, and we also learned that the women of Charleston petitioned the governor to keep a white woman from hanging. They were afraid that it would set a precedent. A “decent” society would not execute a white woman for any crime; the thought of it went against any “civilized” thinking. White women were not hanged in respectable society in the mid 1800s. Why not have mercy on Lavinia and let her go? Why hang a white woman?

What if Lavinia Fisher was not considered to be white?

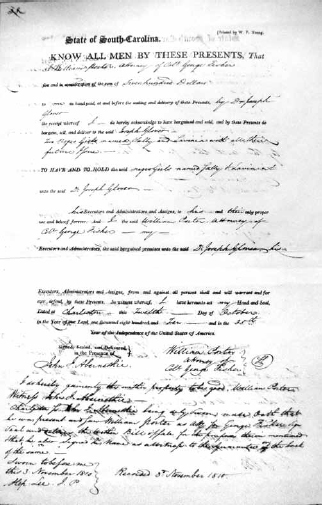

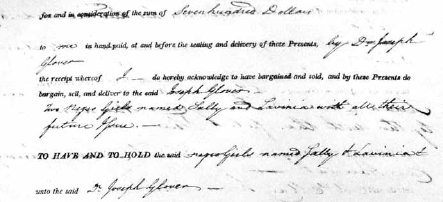

In an 1810 bill of sale to Dr. Joseph Glover, Colonel George Fisher's attorney, William Porter sells two slaves for the sum of $700. We know that slaves were given the surnames of their owners for identification purposes so the obvious last name of these two would be Fisher. The bill of sale is for two young Negro girls. Their names are Sally andâLavinia.

A 1810 bill of sale for two female slaves belonging to Colonel George Fisher, one of which is named Lavinia.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

An enlargement of the bill of sale.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

In 1810, Lavinia Fisher would have been eighteen, young enough to be classified as a girl. This slave would have been an eighteen year old “Lavinia Fisher.” Is this a coincidence that John Fisher's uncle would have owned a slave with the same unusual name as John's future wife? The answer to that is very unlikely. What makes it even less of a coincidence is that Dr. Joseph Glover was a prominent doctor in Charleston, South Carolina. That puts a teenage slave girl by the name of Lavinia Fisher once owned by John Fisher's uncle arriving in Charleston nine years before the incident at the Six Mile House. It is an extremely giant leap to believe this is just a simple coincidence.

Suppose John had taken an interest in a slave of his uncleânot at all uncommon but not popular or accepted. What if his uncle who resided in Rowan County, North Carolina, sold her to a doctor in Charleston, South Carolina, to separate the two young teenagers? It would explain why they were ostracized and why Lavinia's lineage was unable to be traced. Could it be possible that Lavinia was a mulatto, part black and part white with very fair skin? It would explain the descriptors. It would also explain why there has been no marriage documents found. It would explain why John Fisher left North Carolina and his uncle and came back to South Carolina. It would also put a new twist in their tale: a white man in a common law marriage to a black woman in 1819.

As an added note, William Henrys Ross, the grandson of Colonel George Fisher, would marry into the Glover familyâthe family that bought Lavinia.

CONCLUSION

Things Are Not Always as They Appear

We have taken actual court documents, articles, eyewitness accounts and victim statements and established that the true crimes involving John and Lavinia Fisher, William Heyward and the other persons associated with the Six Mile House crimes are quite different than what we have read and been told. As we break down the characters and events, a different story emerges that has us scratching our heads and questioning the legend.

The facts show that the incidents occurred at the Six Mile House, not the Four Mile House as many claim. The house it occurred in was burned to the ground in 1819, which was documented in the news article from that time. The Four Mile House was bulldozed in 1969.

There were no trapdoors used in Six Mile House; there was no cellar full of bodies. Dead folk have a way of turning upâliterallyâduring construction of new buildings as you will soon read. None turned up in the area of the Six Mile House other than the two bodies (and a cow corpse), and there is no evidence they were victims.

On February 14, 1970, just four days prior to the 151st anniversary of the arrests of the Fishers at the same location, groundbreaking began for the Charleston Naval Hospital. There were no unearthed bodies and no uncovered cellars. From the time of its initial groundbreaking and its completion in 1973, nothing of the sort was recovered.

The discovery of bodies does occur periodically as you will soon learn about with the Medical University Basic Science Building's construction, but this was not the case with the hospital.

Charleston Naval Clinic (formerly Charleston Naval Hospital)âthe site where Six Mile House once stood.

Courtesy of author.

We have established that Lavinia was not a witch, a serial killer or the first female hanged in the United States. She did not use seduction or oleander tea to render her victims helpless. She may have once been a slave.

We have likewise proven that John Fisher was not a butcher or a coward. He did not shift the blame to Lavinia. In fact, he protested both her innocence, and his, right up to their executions.

The Fishers did not act alone. There were twelve named members of the gang. Ten were apprehended and four were prosecuted. Three were hanged.

No one was ever charged with murder. Lavinia Fisher was never a serial killer or a murderess. Neither is John Fisher a murderer. They were executed for highway robbery. John Peoples was the only victim that they were executed for. They were tried and convicted on assault to commit murder and common assault on David Ross, but for reasons left to speculation, this case was thrown out and the judges ruled on the Peoples case.

Lavinia was not executed separately from her husband. They were executed together at Meeting Street and the Lines. The Lines was a military barricade and fortification that the militia and citizens of Charleston constructed for defense. The location of where their execution took place would be in the vicinity of Meeting Street and Line Street today.

Lavinia was not executed in her wedding dress. According to Attorney John Blake White's eyewitness account, both of the Fishers were executed in loose white garments placed over their clothing. If Lavinia was executed in her wedding dress, John Fisher wore his wedding dress also. As a matter of fact the Six Mile House was burned to the ground immediately after their arrest. That included all of their property. Lavinia could not have sent someone to retrieve her wedding dress from Six Mile House. It would have been burned months before her execution.

Unless someone bartered for Lavinia's body after the

Charleston Courier

's article, the bodies were buried in Charleston's potter's field. The potter's field was eventually converted to a federal arsenal in 1825. Porter Military School (eventually Porter Gaud Academy) was eventually built over the potter's field in 1880 and the Medical University of South Carolina eventually replaced Porter Military School in 1964.