Six Miles to Charleston (9 page)

Read Six Miles to Charleston Online

Authors: Bruce Orr

The deck now seems to be stacked against the Fishers. They knew of the reputation of Robert Hayne and the conviction of Martin Toohey. They also knew what Toohey's fate was destined to be the following day. Heath did his best, but in the end John and Lavinia were found guilty for the crimes against David Ross. So was William Heyward in his absence. They were charged for the crimes of assault with intent to murder and common assault. They were sent back to jail to await sentencing. Remember, these facts as they will be very important in what happens later.

Less than a week later, on June 2, 1819, John and Lavinia were brought before Judge Charles Jones Colcock for sentencing. As Judge Colcock listened, John Davis Heath presented notice that a motion for a new trial would be made at the constitutional court. The constitutional court was simply a forerunner of the current court of appeals. Judge Colcock made no objections. The constitutional court would not meet again until January, so for now the Fishers were returned to the horrors of the Jail.

In the meantime, William Heyward had managed to find his way to Columbia, South Carolina. Having failed to appear at his May hearing, he was now considered a fugitive. On July 3, 1819, the

Charleston Courier

reprinted an article from the

Columbia Telescope

reporting on Heyward's capture.

Heyward, also known as Howard in this instance, was recognized and identified by a gentleman as he stayed at a hotel in Columbia. He was arrested and detained there until he could be brought back to Charleston to stand trial.

The

Columbia State Gazette

added that Heyward had with him a male and a female, both slaves. The male slave said he had been stolen by Heyward while in Charleston but had difficulty in pronouncing his master's name due to his African dialect. Since no one could interpret the name, no victim could be found and no one could prove that they were not Heyward's slaves.

Upon his arrival back to Charleston, Heyward wrote a letter to the

City Gazette

. In this letter he sought to separate himself from the Fishers. He also expounded on how he did not want to be tried with the others and used this as an excuse as to why he had not returned for trial. He also insisted that he was the one requesting to be brought back to Charleston. Most of this seems to be excuses, but what is significant is a brief excerpt regarding Fisher himself. In an effort to distance himself from John Fisher, Heyward states, “As to Fisher having any farther correspondence with me than dealing in my store, I deny; but as a stranger, what he bought he paid for.” Once again, here is indication that Heyward was the keeper of Five Mile House and that he knew Fisher as an occasional customer, not an inhabitant of Five Mile. Since business was common among the inns, this is another illustration of the separation of Heyward and Fisher as proprietors and the inns they ran.

From a total of twelve members attributed to the gang, the list had been whittled down and now there were three left facing charges. They were the keepers and proprietors of both the Five Mile House and the Six Mile House. They were husband and wife John and Lavinia Fisher and William Heyward. The final threeâand no one elseâwere charged with the crimes against David Ross.

C

HAPTER

5

The Escape

A L

AST

B

ID FOR

F

REEDOM

Because they were husband and wife, John and Lavinia were housed together in a single cell separate from the general population. This was an inner cell on the lowest level generally used as an isolation cell. There was little light or air flow through this cell. Conditions were horrendous.

Apparently there came an opportunity for the Fishers to be moved to another section. According to records, Lavinia pleaded with Sheriff Cleary and both she and John were moved to a less secure part of the jail used as a debtors' prison. Debtors were also held at the jail and manufactured a commodity that the jail had much use forâcoffins.

The debtors' section was in an upper level of the jail where the Fishers could move freely about a larger cell. It was at this location that the Fishers were reunited with Joseph Roberts who was serving out his one-year sentence for assault on the butcher.

On the night of Monday, September 13, 1819, John Fisher and Joseph Roberts created a hole under one of the windows and lowered themselves down with blankets they had tied together. Roberts went out first, followed by Fisher. As Fisher lowered himself to the ground, the blankets broke. He fell approximately twenty feet to the ground. Lavinia could not escape. Her line to freedom had been suddenly severed. Try as he may, John could not save Lavinia that night without alerting the guards. With no alternative, John Fisher and Joseph Roberts escaped into the darkness. Fortunately for them, their escape was not noticed until the following day or they would have had the tracking dogs to contend with.

Escape may have not been the wisest of moves. The authorities of Charleston were still feeling the sting of the escape of Martin Toohey in March. Remember, Toohey had been convicted of the murder of James Gadsden and hanged on May 28, the day after John and Lavinia's trial. He too had been appealed to the constitutional court and had been refused a new trial. Apparently John and Lavinia did not want to take their chances with the court and escaped when the opportunity presented itself. On the heels of the Toohey debacle, this may have sealed their fate with the powers in control of Charleston.

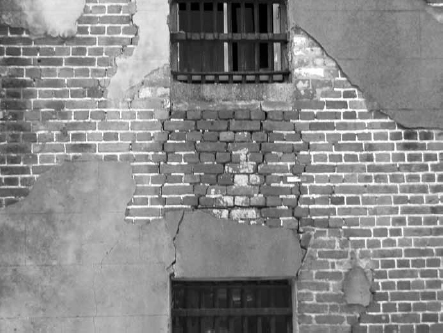

An isolation cell.

Courtesy of author.

Original section built 1802.

Courtesy of author.

A hole under the window in the old section is consistent with escape.

Courtesy of author.

Martin Toohey had been sentenced to hang for the murder of James Gadsden. His brother, Michael had received a lesser charge of manslaughter and had been branded with the letter “M” in his left hand. As Martin Toohey awaited his fate his brothers, Michael and Patrick, conspired with a turnkey, or jailer, for his escape.

On March 17, 1819, Martin Toohey's shackles were discovered, left in his cell undamaged. After investigation, it was determined that a turnkey named Eery had disappeared with him, explaining the undamaged shackles. It was first thought that pirate George Clark had also escaped, but he was later discovered still inside the jail. This “misplacing” of one murderer and the escape of another aided by a turnkey had the city in an uproar.

The governor issued a $1,000 reward and a warning for the citizens to use caution and protect themselves. The Charleston Riflemen were dispatched by the governor in pursuit of the escapee and the corrupt jailer.

The group apparently came upon Martin Toohey in a swampy area outside of Charleston. Two members of the group fired at Toohey, who fled into the woods. Edward Morris, who was mounted on horseback, pursued. Toohey turned and knelt and fired a pistol at Morris. The ball passed through Morris's coat and grazed his chest. A second pistol was fired and the ball went through his sleeve. This time, before Toohey could reload either weapon, Morris caught up with the escapee and struck Toohey in the head with his sword, knocking him to the ground. Other members of the group rushed in and secured him. The wound was obviously pretty gruesome but determined to not be life threatening.

The turnkey, Eery, was captured nearby, and both were escorted back to jail. One was tied to the cart and one was placed inside it. Eery later made a confession, stating he was to have received $600, two watches and coins that were provided by the two brothers and left with a James Riley until Toohey reached safety. Since Toohey had been injured, one assumes that Eerie was the one tied to the cart and dragged behind it back to Charleston. Being dragged behind a cart and his subsequent interrogation prompted the confession.

Another interesting note in the Toohey ordeal is the fact that the Charleston Riflemen brought him back to Charleston to be tried by Attorney General Robert Young Hayne. Hayne had served in the War of 1812 and had become the captain of the Charleston Riflemen in 1814. The fact that Martin Toohey murdered someone, escaped from jail and then fired upon members of a unit his prosecutor had commanded definitely led him to a long drop attached to a short rope.

The jail authorities had a unique interrogation device known as the crane of pain. This device had the prisoners feet shackled to the floor while ropes were attached to each wrist and pulled through a pulley attached to the ceiling. The prisoner would be stretched as far as he could and when he thought he could stretch no more the guards found a way to remedy that. The prisoner then would often be left there for quite some time only to be revisited by the guards, whipped and interrogated. Once having been the deliverer of torture, it appears Mr. Eery now had become the recipient.

Now just six months after the Toohey debacle, Charleston was facing another escape.

On September 15, 1819, the

Charleston Courier

ran a brief article regarding the escape. Governor Geddes had issued a proclamation offering a $500 reward for the apprehension of John Fisher. It states that he had made his escape that Monday evening accompanied by Joseph Roberts. There is no reward mentioned for Roberts at all even though he was serving a yearlong sentence, had escaped from the jail in the past, in addition to a Georgia jail. It seems that although he seemed the most threatening to the citizens of Charleston, it was John Fisher that the governor was most interested in recovering.

Many things have been written about John Fisher and his cowardice. It has also been written that he took every opportunity to blame Lavinia for what they were accused of. In all the research that was conducted in regard to this case and the preparation of this book, one thing is certain: John Fisher was devoted to his wife and defended both her innocence and his until the very end. It is believed that John had planned to board a schooner within the Charleston harbor and sail to Cuba. He would not leave Lavinia behind in Charleston; he stayed in the area, along with Joseph Roberts, trying to devise a scheme to rescue her.

On Tuesday night following the escape, grocer William Bull was keeping late hours at his store on South Bay. He glanced outside and observed two men in the darkness paddling toward shore in a small canoe. One entered the store as the other walked off into the darkness. The customer made a few purchases, but the grocer became suspicious of him. As the man left, Bull secretly followed him and observed him crawl under an overturned boat on the wharf. Bull had a colleague monitor the situation while he left and alerted authorities.

Fisher and Roberts were located hiding under the overturned boat and were rearrested. The

Charleston Courier

reported the events on September 16, 1819: “John Fisher and Joseph Roberts who escaped from the Jail in this city on the evening of the 13th were apprehended on Tuesday night and a number of gold pieces and watches were found in their possession.”

The two men were returned to jail and kept under heavy guard. Both men had the opportunity to escape and flee Charleston. They were given the opportunity, took advantage of it and did indeed escape, but yet both refused to leave Lavinia behind. The breaking of the makeshift rope had left Lavinia to the horrors of the jail, and it appears that John Fisher and Joseph Roberts had spent their brief moments of freedom amassing a bribe similar to the bribe the turnkey received in the Toohey escape. If you recall from earlier, that bribe was $600, two watches and some coins. Perhaps they intended to obtain Lavinia's release much in the same manner Toohey's brothers had obtained Toohey's release.