Six Miles to Charleston (7 page)

Read Six Miles to Charleston Online

Authors: Bruce Orr

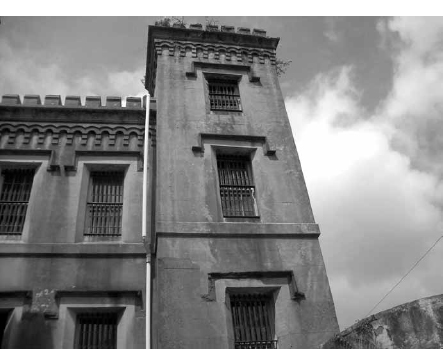

Old City Jail on Magazine Street where the Six Mile gang was held.

Courtesy of author.

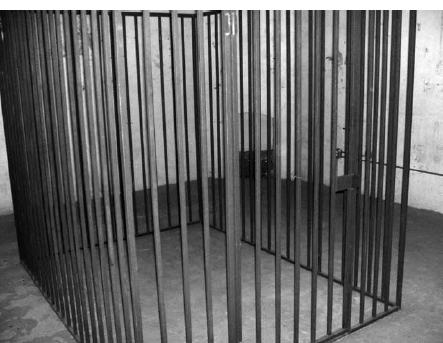

The cage used to house seven to eight inmates

Courtesy of author.

Through the years, the jail underwent many redesigns. In 1822, the architect Robert Mills designed a four-story wing with one-man cells. This was done after public outcry over several escapes of violent prisoners. This wing was taken down in 1855 for the construction of an octagonal wing. That wing was originally four stories with a two-story octagonal tower. The tower and the fourth story were removed in 1886 after being severely damaged in the devastating earthquake that hit Charleston. The jail actually remained in service until 1939.

Punishment for criminal offenses was no picnic either. Colonial punishment was still enforced. Public whippings, or lashings, were inflicted. Whips that were commonly used during that time were referred to as loaded whips. This term is mentioned in David Ross's statement as a weapon having been used against him. A loaded whip is one that has small lead shot sewn into it to add weight as it is swung. This technique gives you the flexibility of a whip and the force of being hit with a steel rod, accompanied by the lacerating effects of the braided leather. Many prisoners received this treatment, were dragged back to their cells through the urine- and feces-soaked wood shavings and left to die. Once they did die, there was no real hurry to remove them. It was not unusual for a corpse to reach an advanced state of decomposition before being removed. It served as a visual reminder for the prisoners to control themselves. The bodies would eventually be removed and taken to the lower section of the jail to be housed in the morgue.

Jailers' quarters.

Courtesy of author.

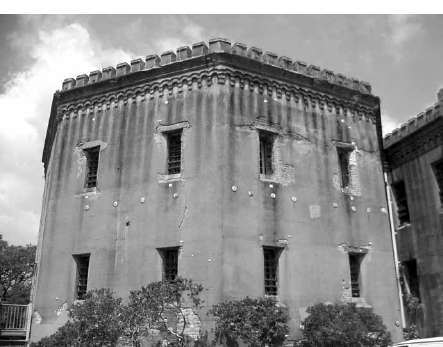

The octagonal section was added in 1855, years after the execution of the Fishers

Courtesy of author.

A section of the jail currently undergoing reconstruction.

Courtesy of author.

Branding was also a common punishment. It also was used as an identifier in marking a person as an offender. Much as the character Hester Pryne was forced to wear the letter “A” for being convicted of adultery in Nathaniel Hawthorne's book,

The Scarlett Letter

, many persons were branded with the first letter of their offense. Michael Toohey, a participant in another crime discussed later in this book, was branded with the letter “M” in the palm of his hand. He was convicted of manslaughter. Another person considered to be a member of the Six Mile House gang had been branded for larceny.

Croppings were also used in the same manner. Part of a person's ear or nose may be cut off or cropped as punishment for a crime they committed. One of the gang members, later to be arrested, showed the harsh evidence of this punishment.

The jail was nothing more than a new aboveground dungeon for the city of Charleston and an improved torture chamber. It may not have been as damp or flooded as bad as the old dungeon, but it had much the same amenities.

During those times the seriousness of the crime was in the eyes of the colonial justice system. The punishment was at the discretion of the judge. A conviction of manslaughter resulting in the death of another may get you branded like Michael Toohey, while an offense of Negro stealing would get you hanged. If the offense was considered serious enough, forfeiting your life was not uncommon back then. The charges facing those associated with the Five Mile House and the Six Mile House were considered egregious enough. Colonial justice does not equal criminal justice. Although the country was moving away from the colonial justice system, Charleston was slow to follow.

As of Monday morning, February 22, 1819, the sheriff, Colonel Nathanial Greene Cleary, had John and Lavinia Fisher, James McElroy, Seth Young, Jane Howard and William Heyward (aka William Hayward or William Howard) in custody, bringing the total to six. The arrests would continue, and the number of the gang members would continue to grow. By that afternoon, James Sterrett would be joining them.

To Sheriff Cleary, James Sterrett was a familiar offender in the city of Charleston. About twelve months prior to this arrest, he had received a branding for a larceny charge. This time he was picked up on a warrant issued by J.H. Mitchell in regard to being a member of the gang and being involved in the assault on David Ross. By the end of the week, the arrests of John Smith and Joseph Roberts would bring the Six Mile House gang's total to nine. They were brought before Mitchell, charged with being accomplices in the gang and committed to jail. The Six Mile gang's trial was set for May in the court of sessions.

William Andrews and F. Davis were never arrested. Remember that these were two of the names that were added to John Peoples's affidavit. Jane Howard was never listed in the court records as one of the suspects, but she was arrested upon Colonel Cleary's arrival at Six Mile House just the same. That makes Lavinia Fisher one of two women associated with the gang and not the sole female as the legend dictates.

One by one the prisoners were brought down to be identified by John Peoples. Remember that according to Peoples's affidavit, it states that, “the deponent doth not know the names of those persons who hath so cruelly beat him and robbed him.” Therefore a lineup of sorts had to be performed. According to Colonel Cleary, there were approximately twenty to thirty witnesses to that identification process to ensure that it was not tainted and Peoples was not swayed in any way.

On March 26, 1819, Philip Walker was a victim of a burglary at his home. Walker was a resident of Goose Creek, a city a little over fifteen miles outside of Charleston. The determined thief had gained entry by prying up part of the flooring of the residence. Once inside he located and carried away a small trunk containing $150.00, three silver watches, clothing, a hat and coat. He then stole a horse belonging to Mr. Walker and fled. Mr. Walker later found his horse in the area of Goose Creek Bridge, but did not locate the thief. Mr. Walker was extremely upset and offered a reward for the recovery of his property.

The offender, René Jacobs, was subsequently captured. Jacobs was located that same night by one of Charleston's police officers. As the

Charleston Courier

reported, it was no use for Jacobs to deny the accusations because he was found wearing Walker's clothing that he had stolen from the residence. The paper further contributes him to the gang of “Land Privateersmen” broken up near the Five Mile House. Jacobs is described as a sea-faring man, and the gang's actions are attributed to them having been schooled in the art of “Patriot Privateering.” In other words, they were being called pirates. This arrest brought the total to ten in custody and two at large. In total, twelve persons were associated with the gang.

The Six Mile gang was not the only criminal elements that Charleston faced at that particular time. As stated earlier, the pirate captain George Clark and members of his crew were housed in the City Jail. Perhaps the example of his capture and incarceration had forced other Patriot Privateers to take up the art of Land Privateering, as the

Charleston Courier

article stated. Apparently land in the Charleston area was much better suited for robbery than the harborâuntil now.

Also housed in the jail was Martin Toohey. Martin Toohey and his gang had murdered James W. Gadsden. Gadsden had been a member of a prominent South Carolina family, but it did not save him from Toohey's knife. Michael Toohey, Martin's brother, had been involved in the crime but received a lesser sentence for manslaughter and received a branding as punishment.

Many of the Six Mile offenders had a criminal history. At twenty-eight years of age, John Fisher had already once been sentenced to receive thirty lashes for theft, but he had been pardoned by the governor on condition he leave not only the city of Charleston but also the entire state of South Carolina.

James Sterrett had been convicted of larceny in Charleston the previous year. He had received a branding as a result.

Joseph Roberts was missing part of his ear. Cropping was still considered as a punishment and apparently he had received this treatment. He had already been held in the jail in 1817 but had escaped the Charleston jail by pretending to belong to a party of visitors. He had also escaped from jail in Savannah, Georgia.

William Heyward was also familiar with the courts of Charleston. He was quite the busy fellow. In 1815, he and a female accomplice were indicted for assault and robbery. He was accused of assaulting Jane Francis, stripping the clothes from her back and robbing her husband. In 1816, he and others were indicted for assaulting three men, including Alfred Huger, a member of one of the more prominent families in Charleston. Again, in 1816, he was found guilty of perjury.

According to the

Charleston Courier

, William Heyward was described as one of the leaders. Remember that there were two houses involved, the Five Mile House and the Six Mile House. After the burning of Five Mile and the removal of the undesirables of Six Mile, David Ross had been put in charge of the Six Mile House. It was apparent from Ross's statement that all the parties had gathered at Six Mile. From investigation it appears that Heyward was the proprietor of Five Mile House. A later article would refer to him as a member of the “five mile house fraternity.” Although all the members were considered part of the same gang, and the terms Five Mile House gang and Six Mile House gang are synonymous and refer to the same group of people, there is a distinct division as to the identity of the inns' proprietors. The Fishers ran Six Mile, and William Heyward ran Five Mile.